Also by

Helen Hoover

A PLACE IN THE WOODS

THE LONG-SHADOWED FOREST

THE YEARS OF THE FOREST

Books For Young Readers:

ANIMALS AT MY DOORSTEP

ANIMALS NEAR AND FAR

GREAT WOLF AND THE GOOD WOODSMAN

This is a BORZOI BOOK

Published by ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Published October 24, 1966

Reprinted Nine Times

Eleventh Printing, April, 1974

Copyright 1965, 1966, by Helen Hoover and Adrian Hoover

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Distributed by Random House, Inc. Published simultaneously in Toronto, Canada, by Random House of Canada Limited.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 66-25612

Portions of this book have appeared in the January 1966, February 1966, and March 1966 issues of Womans Journal, London.

eISBN: 978-0-307-83135-4

v3.1

This book is for

CLAIRE GOMERSALL ,

who always believed in it

Contents

The First Year

PETER

The Second Year

MAMA AND HER TWINS

The Third Year

THE FAMILY

The Fourth Year

THE LONG ROAD

Epilogue

THE GIFT

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My sincere thanks go to Dr. T. D. Nicholson, Chairman, The American MuseumHayden Planetarium, for suggestions which helped my husband prepare his drawing of the heavens; to Dr. John C. Schlotthauer, College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Veterinary Pathology and Parasitology, University of Minnesota, for correcting my paragraphs on deer disease; to Milton H. Stenlund, Game Manager, Minnesota Department of Conservation, for his estimate of the Minnesota timber-wolf population; to James W. Kimball, staff writer, Minneapolis Star & Tribune, for ideas stirred by his column; to the editors of Audubon and Defenders of Wildlife News for permission to adapt material which first appeared in these magazines; to Angus Cameron for his editorial advice; and to my husband, who not only labored mightily on the illustrations but also read and reread the growing manuscript, adding to it from his store of memories.

December 25

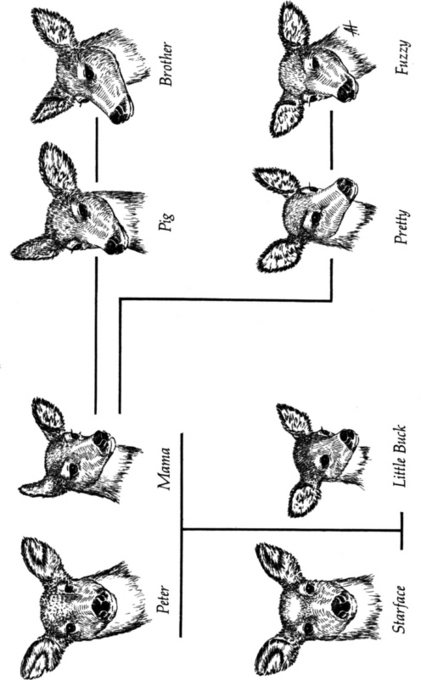

Some fifteen feet from the door of the two-room log cabin where my husband and I have lived every winter and some summers of the past eleven years there is a white cedar tree, one of many in the ancient forest that surrounds the cabin. This tree, seriously damaged by years of scanty rainfall, is dying. Near its roots lies a little pile of branches whose bare, dry twigs give perching space to small birds and cover to timid deer mice and voles. Neither Ade nor I will ever move the branches or fell the tree, even after it is dead, for this was Peter Whitetails tree and the stripped branches are all that remain of green and fragrant cedar cut for him on the memorable day that brought him to our clearing.

Peter was a buck who came to us, not as a fawn but in the fullness of his maturity. To have the trust of any deer is a joy, but when a buck, reserved and cautious as these regal animals are, accepts you as a friendly benefactor it is a very special thing. And Peter was a special kind of buckgentle, generous, great of heart.

So, on a Christmas Day, in the kitchen of our summer cabin

I popped a length of split birch into the purring range, saw that its somewhat doubtful oven thermometer still indicated a proper temperature for turkey roasting, and took the coffee pot from its place on the ring of iron warming trivets that surrounded the stove pipe. As I settled down in the low walnut rocker with my black coffee, I decided that the kitchen would have pleased my Great-aunt Anne, who died in 1932 at the age of ninety-four. The walnut pie safe with sides perforated in patterns, the dry sink with its washpan and dishpan, the oil lamps waiting for the duskeven the fragrance of wood smoke belonged to her era. My plaid wool shirt and heavy leather boots would have pleased her because they are practical, but my woodsmans pants would have shocked her modesty and brought on a tight-lipped silence. However, if she and Uncle John had lived where Ade and I do, forty-five miles from a village on a one-way road, with our nearest neighbor miles away through the vastness of the northern forest, she would have worn pantsand the devil take her critics. Smiling at her memory, I glanced at the clock, a modern alarm which impressed me momentarily as a time traveler in the old-fashioned kitchen. Two thirty, and at least another hour before the bird would be done.

I stood up, stretched, and went into the high-ceilinged living room, closed for the winter because the frame house was not insulated. The rooms dead air was colder by several degrees than the twenty below zero outside, but it felt refreshing after the heat of the kitchen. The walnut Dutch cupboard and maple chairs looked as inhospitable as their counterparts in some museum display room, but glittering frost granules powdered the varicolored stones of the fireplace and icy feathers turned the small-paned windows into luminous miracles of geometric design. I wondered who first owned the furniture and if their ladies had held hand-screens of Berlin work to protect their delicate faces from the heat of other, older fireplaces.

The chill from my own fireplace stones brought me back to the present, and I jumped for the kitchen door. Christmas is for dreaming, but not at the expense of letting the cooking fire go out, especially when we were expecting Jacques Plessis for dinner at four oclock. Jacquess name, pronounced in the French fashion, always sends my summer visitors into ecstatic fantasies of bateaux full of furs and voyageurs, their paddles sweeping through the waters of the border lake that separates our Minnesota shore from Canada, moving down the Voyageurs Highway to the rhythmic chant of Alouette. Actually, Jacques is American-born of parents of French descent and I am sure has never said By gar! in his life. He is an old-time lumberjack, slow and quiet of speech, with the size and strength of these now almost legendary men, and an appetite developed in the days when trees were cut with handsaws. Jacques would lean back in his chair and politely starve if dinner were late.

I knelt by the big oven and poked the bird with a fork. It was time to remove its cloth covering and let it brown. I thought wistfully of the foil I had forgotten to have mailed to us from town, then soothed myself by recalling that Great-aunt Anne had done very well without such luxuries. The turkey would be done on time. I wondered how Ade, a hundred yards away in the winter log cabin, was getting on with his voluntary job of peeling the potatoes and grinding the carrots for salad. I was meditating on the importance of cooperation in small things as well as in large if two people are to live happily in as nearly complete isolation as Ade and I when I heard branches snapping in the woods, loud as little firecrackers in that stillness. I stepped outside.