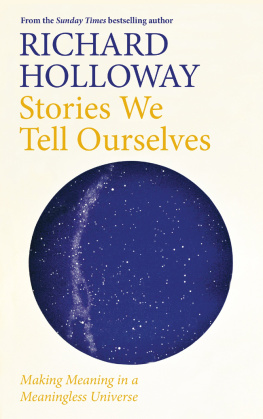

Also by Richard Holloway

Let God Arise (1972)

New Vision of Glory (1974)

A New Heaven (1979)

Beyond Belief (1981)

Signs of Glory (1982)

The Killing (1984)

The Anglican Tradition (ed.) (1984)

Paradoxes of Christian Faith and Life (1984)

The Sidelong Glance (1985)

The Way of the Cross (1986)

Seven to Flee, Seven to Follow (1986)

Crossfire: Faith and Doubt in an Age of Certainty (1988)

The Divine Risk (ed.) (1990)

Another Country, Another King (1991)

Who Needs Feminism? (ed.) (1991)

Anger, Sex, Doubt and Death (1992)

The Stranger in the Wings (1994)

Churches and How to Survive Them (1994)

Behold Your King (1995)

Limping Towards the Sunrise (1996)

Dancing on the Edge (1997)

Godless Morality: Keeping Religion out of Ethics (1999)

Doubts and Loves: What is Left of Christianity (2001)

On Forgiveness: How Can We Forgive the Unforgiveable? (2002)

Looking in the Distance: The Human Search for Meaning (2004)

How to Read the Bible (2006)

Between the Monster and the Saint: Reflections on the Human Condition (2008)

First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

This digital edition first published in 2012 by Canongate Books

www.canongate.tv

Copyright Richard Holloway, 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Grateful acknowledgements are made to Anvil Press for Missing God by Dennis ODriscoll (New and Selected Poems, 2004); Bloodaxe Books for Heaven by A.S.J. Tessimond (Collected Poems, 2010); Carcanet Press for The Two Parents by Hugh MacDiarmid (Complete Poems, Volume I); David Higham Associates for Mutations by Louis MacNeice (Collected Poems, Faber & Faber); Faber & Faber for Murder in the Cathedral by T.S. Eliot; and The Literary Trustees of Walter de la Mare and The Society of Authors as their representative for The Listeners by Walter de la Mare.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future reprints or editions of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 85786 073 6

eISBN 978 0 85786 075 0

Lorna and Gillen

For another day

Demas hath forsaken me, having loved this present world. |

2 Timothy 4:10 |

Come, come, whoever you are, |

Wanderer, worshipper, lover of leaving, |

It doesnt matter. |

Ours is not a caravan of despair. |

Come, come even if you have broken your vows a thousand times. |

Come come yet again, come. |

Rumi |

As one long prepared, and full of courage, |

as is right for you who were given this kind of city, |

go firmly to the window |

and listen with deep emotion... |

to the exquisite music of that strange procession, |

and say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing. |

C.P. Cavafy |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It has been observed recently that editing books is a dying art, but that is far from the case at Canongate. Though I sometimes wearily resented the extra work involved, the attention Nick Davies brought to his reading of my book and the careful suggestions he made about how I might improve it have resulted in a far better book than it would have been had I been left to my own devices. I am most grateful to him as I am to Octavia Reeve, who, at the copy editing stage, made some helpful suggestions as well.

PROLOGUE

THE GRAVEYARD

I f you come this way, not knowing where to look for it, you will probably walk past the graveyard. It is hidden behind a high and impenetrable hedge of yew that looks as if it had been designed to keep out casual visitors. No sign points the way in, and when you succeed in finding it, it looks more like an untidy gap in a thicket than an official entrance. When I was here as a boy, a lifetime ago, the way into the graveyard was wide and clear. It had to be, because this was where we brought our dead in solemn procession to lie in this earth, and here they lie still. The leaflet published by Newark and Sherwood District Council calls the path that takes you there King Charles Walk, because of the tradition that Charles I strolled here while he was held at Kelham Hall in May 1647, after surrendering to the Scots during the Civil War. When I lived here 300 years later, we called it not the Kings but the Apostles Walk, after the clipped yew trees, twelve on each side, which lined the way. We knew the story of the house, but we werent much interested in what had happened here before our arrival, so intent were we on our own purposes. Kelham Hall was by then the mother house of the Society of the Sacred Mission, an Anglican religious order that trained uneducated boys for the priesthood in a monastic setting that was its own world, self-sufficient, entire unto itself. Hoping to be a priest one day, I had been sent here at fourteen from a Scottish back street, and I fell in love with the place and the high purpose it served. After a probationary term in civvies, we were dressed in black cassocks and blue scapulars that set us apart from life outside the great oak gates of the old hall. Our life was military in its discipline and dedication, but it was also full of kindness and laughter. It is the laughter I remember as I walk here again today, taking the path I took so often then, now given back to the memory of the broken king. Change hurts. Or is it deeper than that: is it Time itself we mourn? Time has certainly wrought painful changes here.

The Hall in which Charles was held was rebuilt in 1728 by Bridget, the heiress of the Sutton family, the original owners. When the house Bridget built was gutted by fire in 1857, her descendant, John Henry Manners-Sutton, commissioned George Gilbert Scott to build him a replacement. Presented with what Mark Girouard described as an empty site, a compliant patron, and what seemed a long purse, Scott went to work, and the present Hall was built between 1859 and 1862. The building Scott erected was a smaller, less manic version of Saint Pancras Hotel in London, built a few years after Kelham, and its hard red brick and surprising silhouette still dominate the flat Nottinghamshire landscape for miles around. When Manners-Sutton died in 1898, the mortgage on the property was foreclosed and it came into Chancery.

In 1903 the Society of the Sacred Mission acquired it as their mother house, where they trained boys and young men for the priesthood. In the 1920s, to accommodate increasing numbers, the Society added a new quadrangle, including a massive chapel, the outline of whose huge dome added a softer note to Scotts jagged skyline. Internal difficulties within the Society, and the external pressure of Church of England politics, led to the closure of the college in 1972, and the Society left Kelham. Purchased by them in 1973, it is now the headquarters of Newark and Sherwood District Council, who use the great chapel as an events venue, described in their publicity material as the Dome. When they sold Kelham, the Society retained possession of their graveyard in the grounds, and members of the gradually diminishing order can still elect to be buried there. In their leaflet, Newark and Sherwood District Council describe it as the Monks Graveyard. Coming across it unexpectedly must be like coming upon a corner of a foreign garden that has been set aside for the burial of British residents, and feeling a pang of sorrow that they are so far from home. Though the graveyard does not feel entirely forsaken, it does feel hidden now, which is maybe why I always have difficulty finding it when I make one of my pilgrimages here.

Next page