Also by Richard Holloway

Let God Arise (1972)

New Vision of Glory (1974)

A New Heaven (1979)

Beyond Belief (1981)

Signs of Glory (1982)

The Killing (1984)

The Anglican Tradition (ed.) (1984)

Paradoxes of Christian Faith and Life (1984)

The Sidelong Glance (1985)

The Way of the Cross (1986)

Seven to Flee, Seven to Follow (1986)

Crossfire: Faith and Doubt in an Age of Certainty (1988)

The Divine Risk (ed.) (1990)

Another Country, Another King (1991)

Who Needs Feminism? (ed.) (1991)

Anger, Sex, Doubt and Death (1992)

The Stranger in the Wings (1994)

Churches and How to Survive Them (1994)

Behold Your King (1995)

Limping Towards the Sunrise (1996)

Dancing on the Edge (1997)

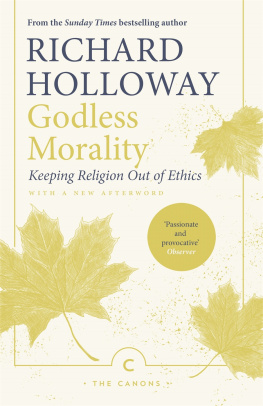

Godless Morality: Keeping Religion Out of Ethics (1999)

Doubts and Loves: What is Left of Christianity (2001)

On Forgiveness: How Can We Forgive the Unforgiveable? (2002)

Looking in the Distance: The Human Search for Meaning (2004)

How to Read the Bible (2006)

Between the Monster and the Saint: Reflections on the Human Condition (2008)

Leaving Alexandria: A Memoir of Faith and Doubt (2012)

A Little History of Religion (2016)

Published in Great Britain in 2018 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2018 by Canongate Books

Copyright Richard Holloway, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted

For permission credits please see p. 166

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any further editions

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78689 021 4

eISBN 978 1 78689 023 8

Typeset in Garamond MT by Palimpsest Book Production Ltd, Falkirk, Stirlingshire

Jeannie,

of course

The present life of men on earth, O King... seems to me to be like this: as if, when you are sitting at dinner with your chiefs and ministers in wintertime... one of the sparrows from outside flew very quickly through the hall, as if it came in one door and soon went out through the other. In that actual time it is indoors it is not touched by the winters storm; but yet the tiny period of calm is over in a moment, and having come out of the winter it soon returns to the winter and slips out of your sight. Mans life appears to be more or less like this; and of what may follow it, or what preceded it, we are absolutely ignorant.

The Venerable Bede

CONTENTS

I

THE DANCE OF DEATH

T he medieval parish church of Saint Mary Magdalene in the town of Newark in Nottinghamshire, England, is a huge building, so you have to look carefully for one of its most interesting features. When it was built in the fifteenth century, England was a Catholic country obsessed with what happened to people after death. It was believed that where you went when you died depended on the kind of life you had lived on earth. For the perfect, for the saint who had lived a life of heroic virtue, there was the prospect of eternal life in heaven. For the wicked, there was the prospect of eternal damnation in hell. It was a dramatic choice between endless joy and unending torment. But the Church has always been good at finding ways to soften its harshest teaching. And thats what happened here.

In the thirteenth century, the Church invented a half-way house between heaven and hell called purgatory, from the Latin for place of cleansing. Purgatory was a moral laundromat, where sinners who had soiled their souls on earth were slowly bleached of their stains and restored to purity. It was painful for them, but unlike the souls in hell, for whom there was never any hope of escape, the souls in purgatory had the prospect of release to cheer them on. And the assistance of the living was another source of encouragement. It was believed that the prayers of those still alive on earth could hasten the cleansing of those in purgatory. The best way to speed them on was to have masses said for them in special chapels called chantries, from the French for chanting. Chantry priests were recruited by wealthy families to pray their relatives through purgatory, much the way a lawyer for a guilty defendant might enter a plea of mitigation on their behalf in order to reduce their sentence.

In 1505, the prosperous Nottinghamshire Markham family built a chantry chapel inside Saint Mary Magdalene and hired a priest to say mass there. On the outside of the stone panels of the little chapel, they painted a favourite subject of medieval artists called the Dance of Death. One panel showed a dancing skeleton holding a carnation, a symbol of mortality. On the other panel there was a richly dressed young man clutching a purse. The skeletons message to the young man was clear. As I am today, you will be tomorrow. And the money in your purse wont help you. It was a memento mori, a prompt to observers remember you must die to make them think about and prepare for their end.

Its a far cry from how we do things today. Now we spend a lot of time and effort not thinking about death. To face our own death is, quite literally, the last thing most of us will do if were conscious enough at the time to do it even then. Even if we wanted to, the chances are we wont have much control over how we leave the scene. Death and dying have been taken over by the medical profession; and theres a lot of evidence to suggest that it sees death not as a friend we might learn to welcome but as an enemy to be resisted to the bitter end. And the end often is experienced as bitter, as a fight we lost rather than as the coming down of the curtain on our moment on the stage, something we always knew was in the script.

People in the Middle Ages didnt have that luxury, if luxury it is. For them, life-threatening illness was as unpredictable and unavoidable as the weather, and they never knew when the lightning might strike. And, considering what came after, it made sense to be prepared for death. In contrast to health professionals today, who advise us to remember the dos and donts of healthy living in order to delay death as long as possible, the medieval Church was an advocate of healthy dying. It produced a guide on how to do it called Ars moriendi (The Art of Dying), a handbook for making a good end. Repenting and confessing your sins was the most important advice they gave the dying. And the reason why is captured by Hamlet in Shakespeares most famous play. The young prince finds his hated stepfather at prayer and decides to kill him:

Now I might do it pat, now he is praying;

And now Ill do it: and so he goes to heaven;

And so am I revenged: that would be scanned:

A villain kills my father; and, for that,

I, his sole son, do this same villain send To heaven.

O, this is hire and salary, not revenge...

Up, sword, and know thou a more horrid hent:

When he is drunk asleep, or in his rage;

Or in the incestuous pleasure of his bed;