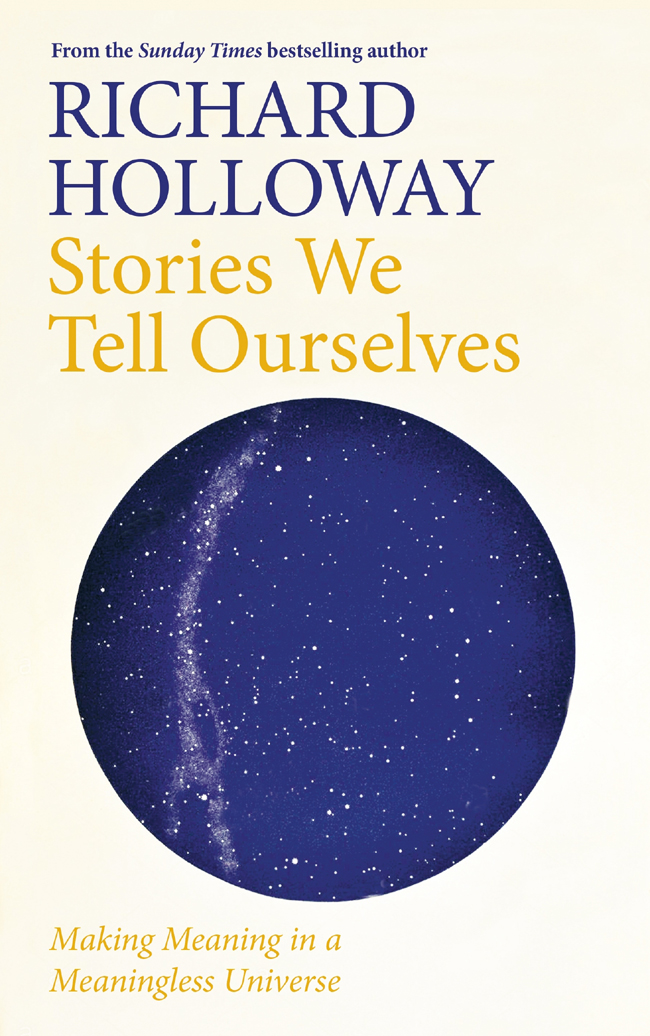

Richard Holloway - Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe

Here you can read online Richard Holloway - Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Canongate Books, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe

- Author:

- Publisher:Canongate Books

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Richard Holloway: author's other books

Who wrote Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also by Richard Holloway

Let God Arise (1972)

New Vision of Glory (1974)

A New Heaven (1979)

Beyond Belief (1981)

Signs of Glory (1982)

The Killing (1984)

The Anglican Tradition (ed.) (1984)

Paradoxes of Christian Faith and Life (1984)

The Sidelong Glance (1985)

The Way of the Cross (1986)

Seven to Flee, Seven to Follow (1986)

Crossfire: Faith and Doubt in an Age of Certainty (1988)

The Divine Risk (ed.) (1990)

Another Country, Another King (1991)

Who Needs Feminism? (ed.) (1991)

Anger, Sex, Doubt and Death (1992)

The Stranger in the Wings (1994)

Churches and How to Survive Them (1994)

Behold Your King (1995)

Limping Towards the Sunrise (1996)

Dancing on the Edge (1997)

Godless Morality: Keeping Religion Out of Ethics (1999)

Doubts and Loves: What Is Left of Christianity (2001)

On Forgiveness: How Can We Forgive the Unforgiveable? (2002)

Looking in the Distance: The Human Search for Meaning (2004)

How to Read the Bible (2006)

Between the Monster and the Saint: Reflections on the Human Condition (2008)

Leaving Alexandria: A Memoir of Faith and Doubt (2012)

A Little History of Religion (2016)

Waiting for the Last Bus (2018)

First published in Great Britain, the USA and Canada in 2020 by

Canongate Books Ltd, 14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Published in the USA by Publishers Group West and

in Canada by Publishers Group Canada

canongate.co.uk

This digital edition first published in 2020 by Canongate Books

Copyright Richard Holloway, 2020

The right of Richard Holloway to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

For permission credits please see p. 239

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and will be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in any further editions

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available

on request from the British Library

ISBN 978 1 78689 993 4

eISBN 978 1 78689 994 1

For Jim and Helen Mein

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

W hether or not we acknowledge it, we all live by the stories we tell ourselves to explain the mystery of our existence, the suffering that accompanies it, and the certain death that concludes it. But our stories do more than offer us explanations for the mystery of existence. They also supply us with rules for living the lives we have been thrust into. The difficulty is in identifying the story we are actually living by. That has certainly been my problem, and I am writing this book to try to resolve it. What story am I trying to live by, and what are its consequences? In a collection of essays published in 1979 called The White Album, Joan Didion captured the main issue:

We tell ourselves stories in order to live... We live entirely... by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the ideas with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience. Or at least we do for a while. I am talking here about a time when I began to doubt the premises of all the stories I had ever told myself, a common condition but one I found troubling.

Here Didion expresses the human dilemma: our need for stories to live by, while acknowledging how precarious and uncertain they are. She then describes the incident that prompted this beginning of doubt in the stories she had told herself.

I... read, in the papers... the story of Betty Lansdown Fouquet, a 26-year-old woman with faded blond hair who put her five-year-old daughter out to die on the center divider of Interstate 5 some miles south of the last Bakersfield exit. The child, whose fingers had to be pried loose from the Cyclone fence when she was rescued twelve hours later by the California Highway Patrol, reported that she had run after the car carrying her mother and stepfather and brother and sister for a long time. Certain of these images did not fit into any narrative I knew.

I know that feeling of uncertainty and discomfort. The Christian religion has been one of the most prolific tellers of the stories by which many of us have tried to live. But what story can it possibly tell that will account for the ancient and abiding sorrows of children? That is the great stumbling block many of us cant climb over in our search for the meaning or purpose of the universe. I have to confess that my discomfort is no longer that of the confident believer who has to fit that incident into the story of how a good God could have come up with a universe in which that kind of thing happens every day. Even when I was telling myself that story, I was never persuaded by the explanations offered by theologians. They demonstrated what to me has always been a weakness in most theological systems: a discomfort with uncertainty that impels a compulsion to explain or account for every mystery under the sun.

I wonder now if this is not a consequence of the male dominance of religious and political systems down the ages. The feminist writer Rebecca Solnit coined the term mansplaining to describe the experience of listening to a man condescendingly explaining something to her he thinks she cannot possibly understand. Its a well-known phenomenon. Solnit attributes it to a combination of overconfidence and cluelessness, a not infrequent combination in the male of the human species. It is rife in Christianity, which has a passion for proclaiming its confident solutions to all the existential puzzles that beset us. I wonder also if male impatience hasnt a lot to do with this rush to judgement and decision. Is it a frustration with the silence of God? An embarrassment? Like those silences that sometimes fall between two people on a long journey which one of them is compelled to fill with nervous chatter? There is certainly a lot of chatter in Christianity. It suggests an unease somewhere, a fear of the void that lies beneath us.

I have always thought believing Jews were more honest about the problem of suffering than believing Christians. There is a scene in Elie Wiesels holocaust novel Night that casts a dark light on the problem. He tells us that one day in Auschwitz they saw three prisoners in chains, one of them a child. He writes:

The SS seemed more preoccupied, more worried, than usual. To hang a child in front of thousands of onlookers was not a small matter. The head of the camp read the verdict. All eyes were on the child. He was pale, almost calm, but he was biting his lip as he stood in the shadow of the gallows...

The three condemned prisoners together stepped onto the chairs. In unison, the nooses were placed around their necks...

At the signal, the three chairs were tipped over...

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe»

Look at similar books to Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Stories We Tell Ourselves: Making Meaning in a Meaningless Universe and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.