An Outlaws Diary:

The Commune

A N O UTLAWS D IARY

THE COMMUNE

by

C C I L E T O R M A Y

An Account of the Bolshevik Revolution in Hungary

Antelope Hill Publishing

The content of this work is in the public domain.

An Outlaws Diary: Volume 2, The Commune by Ccile Tormay first published in 1923, printed in Great Britain, by the Hereford Times ltd., Hereford.

Republished 2020 by Antelope Hill Publishing with the additional subtitle of An Account of the Bolshevik Revolution in Hungary to give added clarity to the modern reader and to present the work as a stand-alone novel, independent of the first volume of this work, which deals with the establishment of the First Hungarian Republic in the Chrysanthemum Revolution.

First printing 2020.

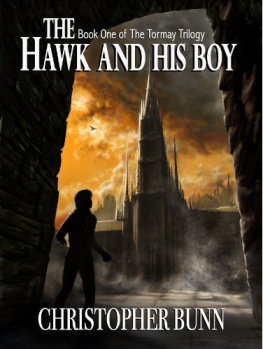

Cover art by sswifty

The publisher can be contacted at

Antelopehillpublishing.com

ISBN-13: 978-1-953730-37-4

Table of Contents

I

Night of March 21st, 1919.

THERE followed a moments silence, the awful silence of the executioners sword suspended in the air. Humanity in bondage draws its head between its shoulders, and, like the sweat of the agonizing, cold rain, pours down the walls of the houses. Now...

A bestial voice shrieks again in the street: LONG LIVE THE DICTATORSHIP OF THE PROLETARIAT!

The neighboring streets repeat the cry. A drawn shutter rattles violently in the dark. Street doors bang as they are hurriedly closed. Running steps clatter past the houses, accompanied by two sounds: Long live... Death... The latter is meant for us. Shots ring out at the street corner.

Death to the bourgeois! A bullet strikes a lamp and there is a shower of glass on the pavement. A carriage drives past furiously, then stops suddenly amid shouts. A confused noise follows and the shooting dies away in the distance. Other cars follow its track into the maddened, lightless town. What is happening there, beyond it, everywhere, in the barracks, in the boulevards? Sailors are looting the inner city: a handful of Bolsheviks have taken possession of the town. There is no escape!

One thought alone contains an element of relief: we have reached the bottom of the abyss. It is disgraceful and humiliating, but it is better than the constant sliding down and down. Now we can sink no lower.

Presently the streets regained their former quiet, and nothing but the throbbing of our hearts pierced the silence. There is no escape for us. The opened gutters have inundated us. St. Stephens Hungary has fallen under the rule of Trotskys agent, Bla Kun, the embezzler. And all round us events are taking place which we have no longer the power to prevent.

I have no idea how long this nightmare lasted. We were silent: everybody was struggling with his own sufferings. The lamp burnt low, and again the clock struck. I caught at its sound, and counted the strokes: nine. Countess Chotek, who had been with us, was there no longer, nor did I see my brother. Time went slowly on. My room appeared to me like the dim background of a painting; figures sat in the picture rigidly, disappeared, and then were there again. The door opened and closed. I saw my journalist friend, Joseph Cavallier, in a chair which had been empty a moment before. He spoke and pressed me to gomad rumours were circulating in the town, awful events were predicted for the night. Lieut.-Col. Vyx and the other members of the Entente missions had been arrested, and it was intended to disarm the British monitors on the Danube. The Russian Red Army was advancing towards the Carpathians, the Bolsheviks had declared for the integrity of our territory. Bla Kuns Directorate had declared war on the Entente. You must escape to night, said my friend; they are going to arrest you. Come to us.

My mother called me and I opened her door with apprehension. She was sitting up in bed, propped high between the pillows: her face was livid and appeared thinner than ever. She too had heard the cries in the street, was aware of what had happened, and knew what was in store for us. Her haggard, harassed look inspired me with strength to face our fate.

Why dont you come here? Why cant we talk things over in here? She did not mean to cause pain, but her words stabbed me. Poor dear mother!

When Joseph Cavallier told her of his proposal she shook her head:

You live on the other side of the river, dont you? Dont let her go so far. Suddenly she recovered herself and turned to me: It is raining hard and I heard you coughing so badly all day.

The others had followed us into her room, and all had something to say. My sister-in-law mentioned her brother Zsigmondy who lived nearby: he had offered me shelter in his home. My mother alone was silent. Though she could not say it, it was she who was most anxious for me to go. She looked at me imploringly. That decided me. It can only be a question of a day or two, I said. Then, when they have failed to find me here, I can come back.

Did I believe what I said? Did I imagine that things would happen like that? Or did I attempt to deceive myself so that I might bear it the more easily? I noticed a deep shadow that stole suddenly, I knew not whence, over my mothers face. It appeared on the other faces too, as if all of them had aged suddenly. And beyond them, around us, in the houses opposite, all over the town, people aged suddenly in that ghastly hour.

They all went away and left me alone in my room. I knew I ought to hurry, yet I stood idle in front of the open cupboard. How many, I thought, are standing, hesitating like this tonight, how many are hurrying and running aimlessly about, not knowing whither to turn? Will it be the same here as in Russia? Quietly the door opened behind me: my mother had risen and came to me so that we might be together as long as possible.

I will take just a few things, very few, I kept repeating, as if I wanted to force the hand of fate to make my trial short. Perhaps I may be able to come home tomorrow

My mother did not answer. She tied the parcels together for me.

The housekeeper must not know till tomorrow morning that you have gone... She looked out into the anteroom to see that no one was about, then opened the door herself and accompanied me down the corridor. The house seemed asleep, the sky was black, and the courtyard underneath was like a dark shaft, in which rain-water had accumulated.

Leaning on my arm my mother walked along with me. In silence both of us struggled to keep control over our emotions. At the front door we stopped. Nothing was audible but the patter of the rain. My mother raised her hand and passed it over my face, caressingly, as though she would feel the outlines that she knew so well.

Take every care of yourself, my dear, dear one!

I was already running down the stairs. She was leaning over the balustrade, and I heard her voice behind me, keeping me company as long as possible, calling softly, Good-night!

Good-night... I called back, but my voice failed me in a pain such as I had never felt before.

Beyond the street door there was a rattle of gunfire. I tried to keep cheerful, and kept saying: Tomorrow I shall come back to her, tomorrow. I groped my way across the dark yard and knocked at the concierges window. He came out, looking curiously at me in the glare of his lantern: There is a lot of shooting out there. It would be wiser to stay at home. But I shook my head and the key turned in the lock; the door opened stealthily, and closed carefully behind me, as though unwilling to betray me.

Next instant I stood alone in the rain. I shuddered: my retreat was cut off. Home, everything that was good, everything that protected me, was behind that door, beyond my reach.

Next page