Peter Stothard - Spartacus Road

Here you can read online Peter Stothard - Spartacus Road full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: The Overlook Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Spartacus Road

- Author:

- Publisher:The Overlook Press

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Spartacus Road: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Spartacus Road" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Spartacus Road — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Spartacus Road" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Peter Stothard is the editor of the Times Literary Supplement. He was editor of the Times from 1992 to 2002 and writes on modern politics and ancient literature. His previous book, 30 Days: A Month at the Heart of Blairs War, is a diary of his time observing the direction of the 2003 conflict in Iraq.

To the books that came on the road: Appian, The Civil Wars, Penguin Classics, 1996; Cicero, On Ends, Loeb Classical Library, 1931; Claudian, Poems, Loeb, 1922; Florus, Epitome of Roman History, Loeb, 1929; Frontinus, Stratagems, Aqueducts of Rome, Loeb, 1925; Giovagnoli Raphael, Spartacus, Albin Michel, Paris, 1920; Horace, Satires 1, Aris and Phillips Classical Texts, 1993, Opera, Oxford Classical Texts; Koestler, Arthur, The Gladiators, Vintage Classics, 1999; Livy, History of Rome, Loeb, 1929; Pliny, Letters, Loeb, 1969; Plutarch, Lives, Loeb, Vol 3, 1916; Statius, Silvae and Thebaid, Loeb, 1928 and 2003.

To other books: An Iron Age and Roman Republican Settlement on Botromagno, Gravina di Puglia, Alastair Small, British School at Rome, 1992; Archytas of Tarentum, Pythagorean, Philosopher and Mathematician King, Carl A. Huffman, CUP, 2005; Aulus Gellius, Leofranc HolfordStrevens, Duckworth, 1988; Ausonius, Poems, Loeb, 1919; Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World, Richard J. A.Talbert (ed), Princeton, 2000; Cowper, William, Poetical Works, Edinburgh, 1864; Drummond, William, Poems and Prose, Scottish Academic Press, 1976; Epicurus on Freedom, Tim OKeefe, CUP 2005; Facing Death, Epicurus and his Critics, James Warren, OUP 2004; Horace, Odes Bk III, A Commentary, R. G. M. Nisbet and Niall Rudd, OUP, 2004; Marcus Crassus and the Late Roman Republic, Allen Mason Ward, University of Missouri Press, 1977; Sallust, The Histories, Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1994; Statius, Silvae 5, Bruce Gibson (ed), OUP, 2006. Symmachus, A Political Biography, Cristiana Sogno, Ann Arbor, 2006; Symmachus, Letters, J. P. Callu (ed), Paris, 197282; Thinking Tools, Agricultural Slavery between Evidence and Models, Ulrike Roth, Institute of Classical Studies, 2008; Troy between Greece and Rome, Andrew Erskine, Oxford, 2001.

To Sally Emerson, as ever; to Robert Wolff of Houston, Chris Russell, Martyn Caplin, Daniel Hochhauser and Bill Lees of London, masters of medicine; to Belinda Theis; to all Italian hosts, particularly the Raito Hotel in Salerno and the Tramontano in Sorrento, no better places to write about Epicurus; to William Goodacre of Tastes of Italy; to Peter Brown and Trinity College, Oxford; to Mary Beard, Christopher Kelly and Malcolm Schofield of Cambridge, who read the text; to Paul Webb; to Martin Redfern and Annabel Wright at HarperCollins; to Maureen Allen and Roz Dineen at the TLS ; to my peerless agent, Ed Victor, and to my daughter and son, Anna and Michael Stothard, without whom this book would not be as it is and to whom it is dedicated.

This Spartacus Road begins high on Romes most southeasterly hill, the Caelian, with questions that were asked here first some five hundred years after the great slave revolt. How could twenty-nine gladiators have strangled themselves in their underground pens? How did they dare to do it? How had they succeeded in doing it? There was no rope, no cloth, nothing to make a noose. The games had barely begun and twenty-nine men had suddenly been their own stranglers. Somehow it had happened. How?

These were not the questions which Quintus Aurelius Symmachus most wanted to ask. A power-broker of an age when his city had lost so much power liked to think of better things. Life was too short, its needs too great, for anyone, let alone him, to agonise over some ingeniously suicidal Saxons.

He had his duties as ambassador between the old Rome and the new, the pagan and the Christian. Romes rulers in Constantinople and Milan were militant leaders of the new ruling faith. Many of their subjects, his own people here among the empty barracks and neglected temples, were more relaxed in their religious commitments. Symmachus needed all his old Romans diplomatic skills to mediate between the two.

He had serious private interests as a writer and intellectual, a word he would happily have used of himself had he known it. He was self-important, self-reliant, subtle in his own cause, fond of focusing on himself in every way. Now one of the least read writers of ancient Rome, his nine hundred surviving letters and forty-nine reports to the rulers of his world are reminders of a time when he could demand to be read.

In the year ad 393, he was just over fifty years old. He had already held the thousand-year-old office of city prefect, a title whose antiquity was of some importance to him. True, he had not held the city prefecture very long: but brief tenures in office were nothing now of which to be ashamed. Holding on to any job, or even any consistent line of thought, was difficult when commands and signals came from two imperial courts, in east and west, so very far away and apart.

At least he had added a prefects distinction to his family line. Symmachus was still a Roman senator, a senior priest whose sway extended from Vestal virgins to omens of war, a man of wealth in gold and land to protect against what sometimes seemed the end of his world. On this troubled Roman morning, four centuries after the death of the first Caesar, he had greater anxieties to express in his letter to his brother than a mass immolation of twenty-nine men from the cold, dank north.

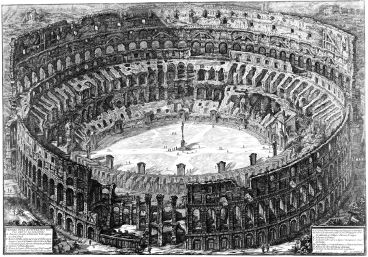

How much did he or anyone really care how the gladiators had died? They were captives condemned to appear in the Colosseum arena. He could see down to their last killing place from up here at his Caelian home. Their miserable heads had been unable to save their miserable necks. Those same heads had decided to break those necks. How had they done it? Who could tell?

He could see silvery streaks in the southern Roman sky, the first morning lights on the high arches built by great warrior emperors of old. This was only the second day of his games, only the start of his latest personal offering for the entertainment of the Roman people. Yesterday had been disastrous but there was much more still to come. Above the soaring marble was the fading array of stars at dawn. Symmachus, like many in uncertain times, found much contemplative comfort in the stars.

His first thought? No one had directly killed himself. Not even the toughest gladiator is tough enough to be his own strangler. All human grip fails before the body is dead. Second thought. Maybe the Saxons had a leader, an elected executioner or one chosen by lot, who stood behind each prisoner in line, choking the breath of one, then another, breaking the bones, stopping the blood. That was possible but not likely. Leadership of such an enterprising kind would surely have been detected and corrected before they arrived.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Spartacus Road»

Look at similar books to Spartacus Road. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Spartacus Road and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.