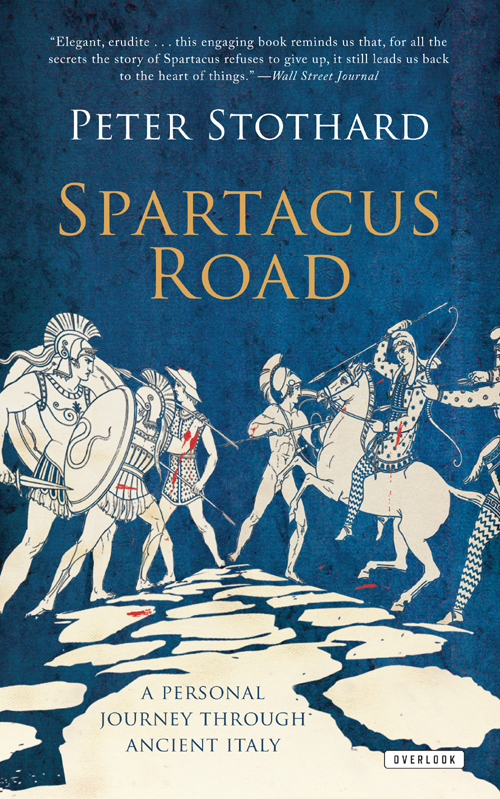

Peter Stothard - The Spartacus Road

Here you can read online Peter Stothard - The Spartacus Road full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2010, publisher: Overlook Hardcover, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Spartacus Road

- Author:

- Publisher:Overlook Hardcover

- Genre:

- Year:2010

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Spartacus Road: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Spartacus Road" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Spartacus Road — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Spartacus Road" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This edition first published in paperback in the United States in 2012 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact

Copyright 2010 by Asp Words

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-158-8

To Anna and Michael

In the final century of the first Roman Republic an army of slaves brought a peculiar terror to the people of Italy. Its leaders were gladiators. Its purpose was incomprehensible. Its success was something no one had ever known. Never before had the worlds greatest state been threatened from the lowest places that its citizens could imagine, from inside its own kitchens, laundries, mines, fields and theatres. Never again, the victors said when Spartacus was dead and his war was over.

The Spartacus Road is the route along which the slave army fought its Roman enemies between 73 and 71 BC. It is a road much travelled then and since by poets and philosophers, politicians and teachers, torturers and terrorisers of different times, those living today and those long ago dead, innovative thinkers about fear and death, some with truths to teach us, others whom we can try to forget. It stretches through 2,000 miles of Italian countryside and out into 2,000 years of world history. From Sicily to the Alps and from Paris to Hollywood, it has never wholly left the modern mind.

This book is a diary of a journey on that Spartacus Road. It is, in part, a journalists notebook because I have been a journalist a newspaper reporter and editor for most of my life. It is a classicists notebook, written with half-remembered classical books for company, because while reporting politics in our own time I have so often felt the beat of ancient feet. It is also the notebook of a grateful survivor: ten years ago I was given no chance of living to make this trip and, on the Spartacus Road, the memory of a fatal cancer and its fortuitous cure shone stronger, and stranger, than I ever thought it could.

Little of this book is as I thought it might be. It began as notes written night by night, on bar tables and brick walls, in the places where the Spartacus War was fought. It became a history of that war, the best that I could write, and the history of how I came to know anything about that war, other wars, and many other things.

Thanks are owed to Greek and Roman writers whom I thought I knew when I was young and know differently now. Returning to old books is like returning to old friends. They have changed, both the familiar characters studied at school and some of the less read ancients, a director of Roman water supplies, a historian who was a lovable tabloid hack, a pioneer writer on interior dcor and on the apocalypse. Thanks too to some equally little-known twenty-first-century travellers, a pair of Koreans, an actor seeking centurion roles, a Pole selling DVDs and a bibulous priest.

The barest facts about Spartacus, like the road itself, are often hard to find. They disappear and reappear in the landscape and in the memory of succeeding centuries. They have been twisted in the service of cinema, politics and art. There is Spartacus the romantic gladiator from Thrace, the fighter for freedom, the man who lives on in the memory of emulators; and there is Spartacus the terrorist and threat to life, the one who survives in others fears. There is the hidden man and the man of the Spectacular, the word which appeared on the first page of my first notes, the Romans own name for the theatrical games and aesthetic of death that so powerfully defined both their lives and our memories of them.

This Spartacus Road begins high on Romes most southeasterly hill, the Caelian, with questions that were asked here first some five hundred years after the great slave revolt. How could twenty-nine gladiators have strangled themselves in their underground pens? How did they dare to do it? How had they succeeded in doing it? There was no rope, no cloth, nothing to make a noose. The games had barely begun and twenty-nine men had suddenly been their own stranglers. Somehow it had happened. How?

These were not the questions which Quintus Aurelius Symmachus most wanted to ask. A power-broker of an age when his city had lost so much power liked to think of better things. Life was too short, its needs too great, for anyone, let alone him, to agonise over some ingeniously suicidal Saxons.

He had his duties as ambassador between the old Rome and the new, the pagan and the Christian. Romes rulers in Constantinople and Milan were militant leaders of the new ruling faith. Many of their subjects, his own people here among the empty barracks and neglected temples, were more relaxed in their religious commitments. Symmachus needed all his old Romans diplomatic skills to mediate between the two.

He had serious private interests as a writer and intellectual, a word he would happily have used of himself had he known it. He was self-important, self-reliant, subtle in his own cause, fond of focusing on himself in every way. Now one of the least read writers of ancient Rome, his nine hundred surviving letters and forty-nine reports to the rulers of his world are reminders of a time when he could demand to be read.

In the year ad 393, he was just over fifty years old. He had already held the thousand-year-old office of city prefect, a title whose antiquity was of some importance to him. True, he had not held the city prefecture very long: but brief tenures in office were nothing now of which to be ashamed. Holding on to any job, or even any consistent line of thought, was difficult when commands and signals came from two imperial courts, in east and west, so very far away and apart.

At least he had added a prefects distinction to his family line. Symmachus was still a Roman senator, a senior priest whose sway extended from Vestal virgins to omens of war, a man of wealth in gold and land to protect against what sometimes seemed the end of his world. On this troubled Roman morning, four centuries after the death of the first Caesar, he had greater anxieties to express in his letter to his brother than a mass immolation of twenty-nine men from the cold, dank north.

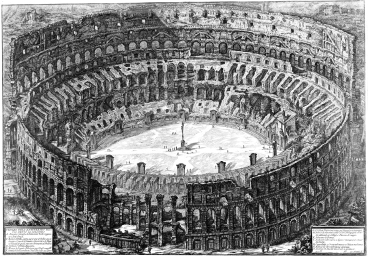

How much did he or anyone really care how the gladiators had died? They were captives condemned to appear in the Colosseum arena. He could see down to their last killing place from up here at his Caelian home. Their miserable heads had been unable to save their miserable necks. Those same heads had decided to break those necks. How had they done it? Who could tell?

He could see silvery streaks in the southern Roman sky, the first morning lights on the high arches built by great warrior emperors of old. This was only the second day of his games, only the start of his latest personal offering for the entertainment of the Roman people. Yesterday had been disastrous but there was much more still to come. Above the soaring marble was the fading array of stars at dawn. Symmachus, like many in uncertain times, found much contemplative comfort in the stars.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

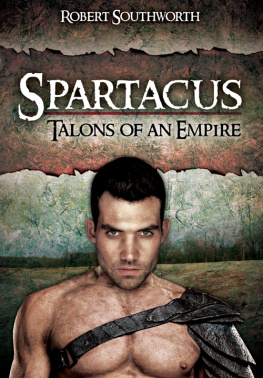

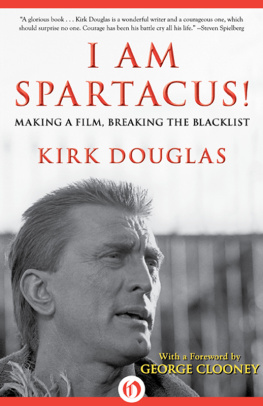

Similar books «The Spartacus Road»

Look at similar books to The Spartacus Road. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Spartacus Road and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.