Contents

Guide

For My Wife Yoshie

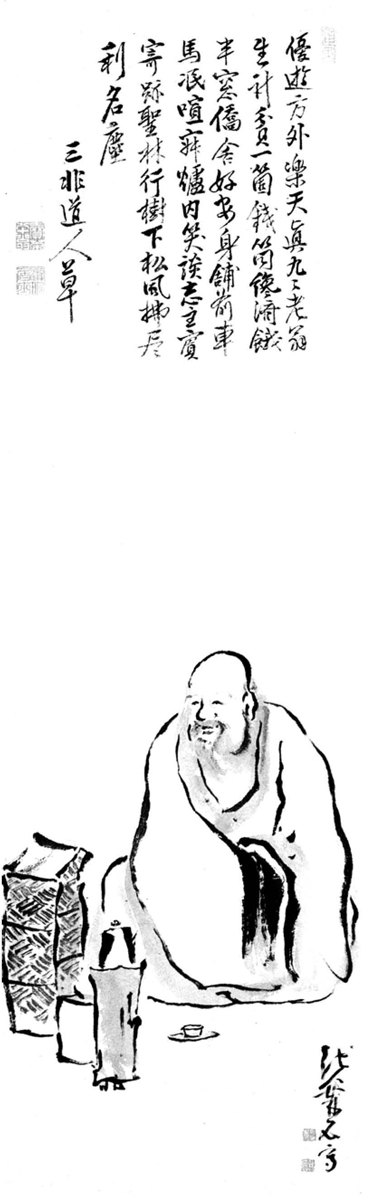

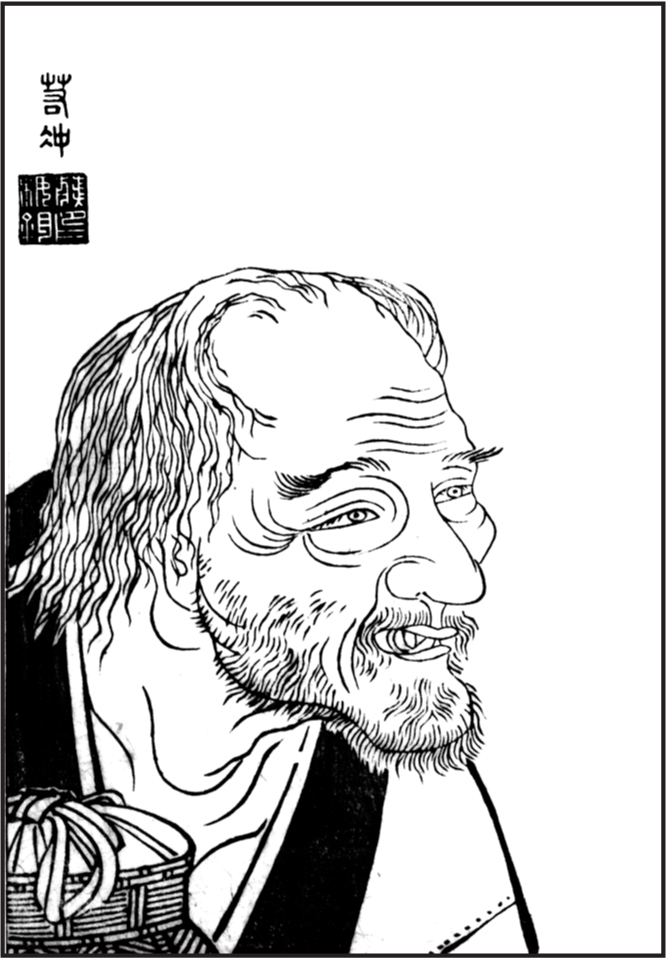

Portrait of Baisa. Ike Taiga. Inscription by Baisa. Reproduced from Eastern Buddhist, No. XVII, 2.

The man known as Baisa, old tea seller, dwells by the side

of the Narabigaoka Hills. He is over eighty years of age,

with a white head of hair and a beard so long it seems

to reach to his knees. He puts his brazier, his stove,

and other tea implements in large bamboo wicker

baskets and ports them around on a shoulder pole.

He makes his way among the woods and hills, choosing

spots rich in natural beauty. There, where the pebbled

streams run pure and clear, he simmers his tea and offers

it to the people who come to enjoy these scenic places.

Social rank, whether high or low, means nothing to him.

He doesnt care if people pay for his tea or not.

His name now is known throughout the land.

No one has ever seen an expression of displeasure cross

his face, for whatever reason. He is regarded by one

and all as a truly great and wonderful man.

Fallen Chestnut Tales

Contents

Introductory Note

THE BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH of Baisa in the first section of this book has been pieced together from a wide variety of fragmented source material, some of it still unpublished. It should be the fullest account of his life and times yet to appear. As the book is intended mainly for the general reader, I have consigned a great deal of detailed factual information to the notes, which can be read with the text, afterwards, or disregarded entirely.

The translations in the second part of the book represent all of Baisas published verse and prose as well as some additional verse taken directly from holograph manuscripts. With the exception of the holograph texts, all translations are based on the standard two-volume edition of Baisas works compiled by Fukuyama Chgan.

Dates are given as they appear in the original texts, according to the lunar calendar. This means they fall roughly five or six weeks earlier than their Western equivalents; for example, reference in a text to the first of the second month would in the Western calendar fall sometime during the first half of March. However, I have converted Japanese ages, which were traditionally derived from a system that counted newborns as one year old, to conform to Western convention by subtracting a year.

I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere gratitude to the many collectors and art dealers, past and present, who have allowed me to examine and photograph Baisa letters and calligraphy in their collections, and to acknowledge a debt of thanks to the late Tanimura Tameumi for introducing me to little-known sites connected with Baisas life in and around Kyoto. More recent obligations are to Yoshizawa Katsuhiro of the International Institute of Zen Studies in Kyoto and to the baku scholar tsuki Mikio, who generously gave their valuable time to share their expertise with me.

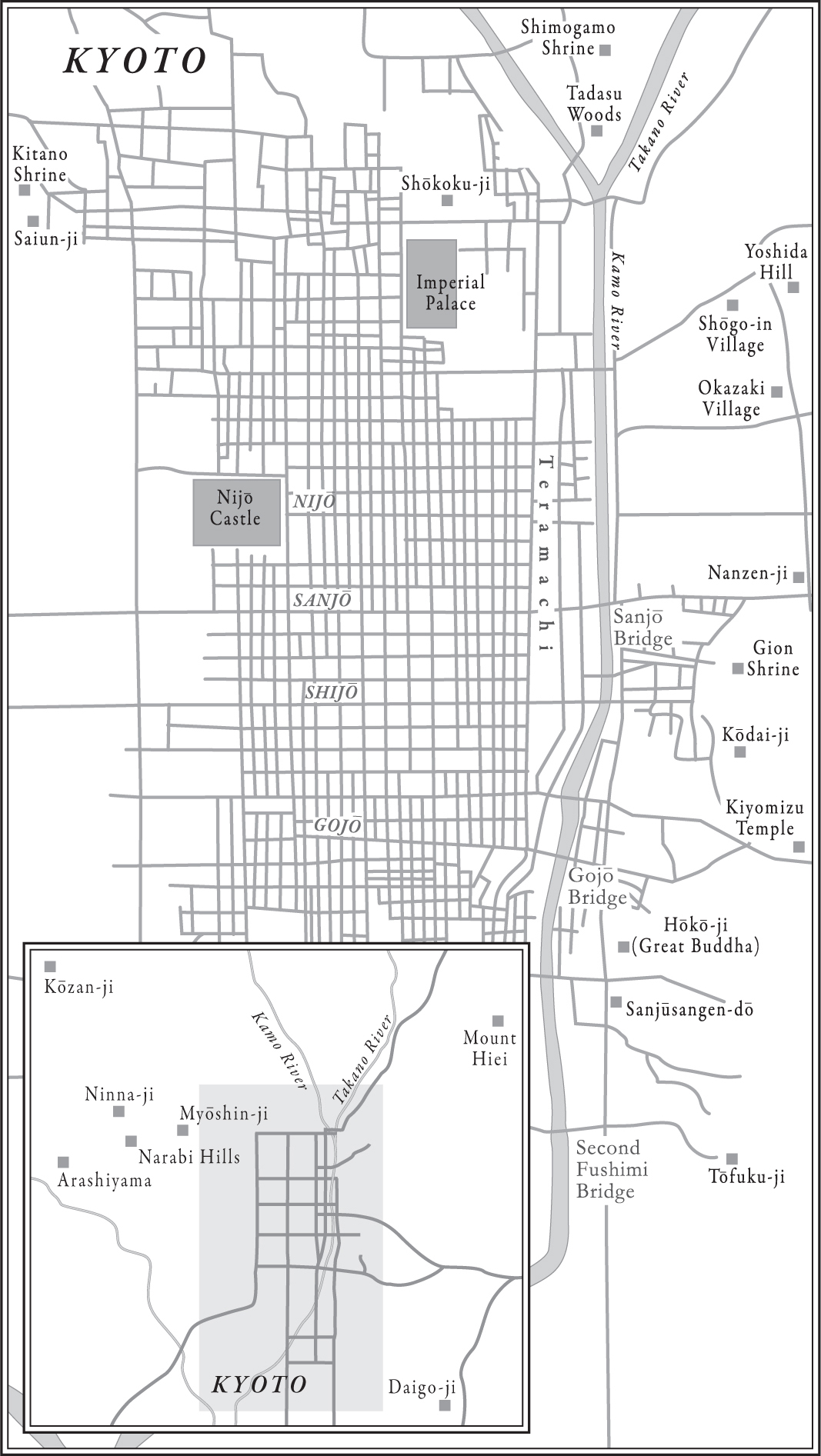

18th Century Kyoto

Life of Baisa

INTRODUCTION

I N THE FOURTH month of 1724 the priest Gekkai Gensh, then in his late forties, left the Zen temple in the castle town of Hasuike on the southernmost Japanese island of Kyushu, where he had served for thirty-eight years, and set out for the capital at Kyoto, some five hundred miles distant. After a decade or so which he apparently spent wandering around the Kyoto/Osaka region, he took up residence in a small dwelling on the banks of the Kamo River in Kyoto, earning a living at the age of sixty by selling a new type of tea known as sencha, made by infusing leaves in a teapot.

He soon became a familiar figure around the capital, known simply by the sobriquet he had adopted, Baisa, the Old Tea Seller. His shop was frequented by ordinary citizens as well as by many of those at the center of the citys artistic, literary, and intellectual life. Baisa forged lasting friendships with his remarkable clientele of leading poets, writers, painters, calligraphers, and scholars of the Edo period, a set of congenial spirits who made early eighteenth-century Kyoto one of the finest and most interesting cities anywhere in the world.

In addition to selling tea at his place of residence, Baisa was soon taking his shop outdoors. Shouldering his tea equipment, balanced in large portable bamboo-wicker baskets on the ends of a carrying pole, he could set up for business wherever he wished, choosing sites among the many celebrated scenic locales in Kyoto and the surrounding hills.

Baisa did not charge a fixed price for his tea, relying instead on donations left by customers. Although these alms usually were enough to buy the small amount of rice he needed to sustain himself and were occasionally supplemented by gifts of staples such as miso and shoyu, his poems describe times of great extremity when, foodless and penniless, he was reduced to begging.

For the first ten years of his residence in Kyoto, Baisa remained a priest, going against Buddhist regulations pointedly forbidding clerics to earn their own living. When at the age of sixty-seven circumstances arose that obliged him to leave the priesthood, forfeit his Buddhist names, and revert to lay status, he adopted the secular name K Ygai, which he and his friends often shortened to Layman Ygai.

In his eighties, Baisa was crippled by severe back pains that made it impossible to continue carrying his tea equipment around the city. He burned his favorite carrying basket and other tea utensilsto keep them, he said, from falling into vulgar handsand began to eke out a living from writing calligraphy and from selling tea at his shop, which now, after many moves, was located in the village of Shgo-in in Kyotos eastern suburbs.

In the seventh month of 1763, Baisa passed away peacefully at the age of eighty-eight. Shortly before, his friends had put in his hands a copy of the Baisa Gego (Verses and Prose by the Old Tea Seller), a collection of Chinese writings he had composed in the course of his tea-selling life, which they had prepared and printed.

The earliest account of Baisas life is the one compiled by his young friend Daiten Kenj, a Shkoku-ji priest, as an introduction for the Baisa Gego. This became the basic source for most of the brief sketches of Baisa that appeared prior to the twentieth century. In piecing together the present work I have followed quite closely the chronology established by the modern Baisa scholar Tanimura Tameumi. Thanks to new material in letters and inscriptions found in private collections and sales catalogs that I have been able to discover in the decades since Tanimuras work was published, I believe that I have been able to emend or clarify his research in some places.