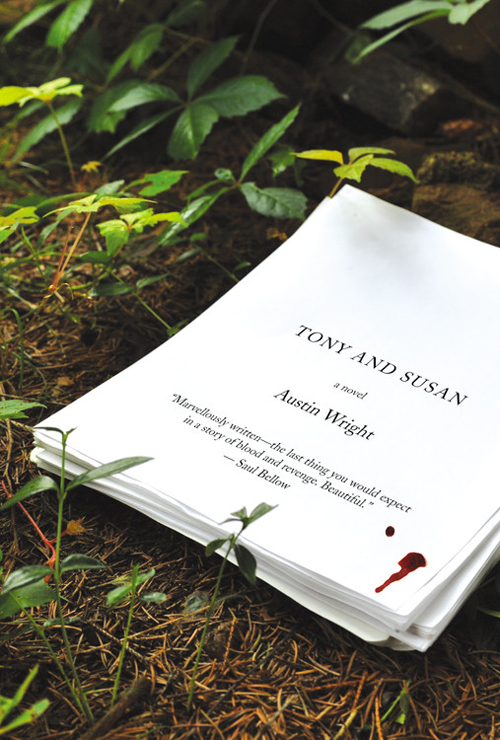

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is coincidental.

Copyright 1993 by Austin Wright

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Grand Central Publishing

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com

www.twitter.com/grandcentralpub

First eBook Edition: August 2011

ISBN: 978-0-446-58290-2

Grand Central Publishing is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Grand Central Publishing name and logo is a trademark of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

BEFORE

This goes back to the letter Susan Morrows first husband Edward sent her last September. He had written a book, a novel, and would she like to read it? Susan was shocked because, except for Christmas cards from his second wife signed Love, she hadnt heard from Edward in twenty years.

So she looked him up in her memory. She remembered he had wanted to write, stories, poems, sketches, anything in words, she remembered it well. It was the chief cause of trouble between them. But she thought he had given up writing later when he went into insurance. Evidently not.

In the unrealistic days of their marriage there was a question whether she should read what he wrote. He was a beginner and she a tougher critic than she meant to be. It was touchy, her embarrassment, his resentment. Now in his letter he said, damn! but this book is good. How much he had learned about life and craft. He wanted to show her, let her read and see, judge for herself. She was the best critic he ever had, he said. She could help him too, for in spite of its merits he was afraid the novel lacked something. She would know, she could tell him. Take your time, he said, scribble a few words, whatever pops into your head. Signed, Your old Edward still remembering.

The signature irritated her. It reminded her of too much and theatened the peace she had made with her past. She didnt like to remember or slip back into that unpleasant frame of mind. But she told him to send the book along. She felt ashamed of her suspicions and objections. Why hed ask her rather than a more recent acquaintance. The imposition, as if what pops into her head were easier than thinking things through. She couldnt refuse, though, lest it look like she were still living in the past. The package arrived a week later. Her daughter Dorothy brought it into the kitchen where they were eating peanut butter sandwiches, she and Dorothy and Henry and Rosie. The package was heavily taped. She extracted the manuscript and read the title page:

NOCTURNAL ANIMALS

A Novel By

Edward Sheffield

Well typed, clean pages. She wondered what the title meant. She liked Edwards gesture, reconciling and flattering. She had a sneaky feeling that put her on guard, so that when her real husband Arnold came in that night, she announced boldly: I heard from Edward today.

Edward who?

Oh, Arnold.

Oh Edward. Well. What does that old bastard have to say for himself?

That was three months ago. Theres a worry in Susans mind that comes and goes, hard to pin down. When shes not worrying, she worries lest shes forgotten what shes worrying about. And when she knows what shes worrying about, like whether Arnold understood what she meant, or what he meant when he said what he meant this morning, even then she has a feeling its really something else, more important. Meanwhile she runs the house, pays the bills, cleans and cooks, takes care of the kids, teaches three times a week in the community college, while her husband in the hospital repairs hearts. In the evenings she reads, preferring that to television. She reads to take her mind off herself.

She looks forward to Edwards novel because she likes to read, and shes willing to believe he can improve, but for three months she has put it off. The delay was not intentional. She put the manuscript in the closet and forgot, remembering thereafter only at wrong times, like while shopping for groceries or driving Dorothy to her riding lesson or grading freshman papers. When she was free, she forgot.

When not forgetting, she would try to clean out her mind to read Edwards novel in the way it deserved. The problem was old memory, coming back like an old volcano, full of rumble and quake. All that abandoned intimacy, his out-of-date knowledge of her, and hers of him. Her memory of his admiration of himself, his vanity, also his fearshis smallnessknowledge she must ignore if her reading was to be fair. Shes determined to be fair. To be fair she must deny her memory and make as if she were a stranger.

She couldnt believe he merely wanted her to read his book. It must be something personal, a new twist in their dead romance. She wondered what Edward thought was missing in his book. His letter suggested he didnt know, but she wondered if there was a secret message: Susan and Edward, a subtle love song? Saying, read this, and when you look for what is missing, find Susan.

Or hate, which seemed more likely, though they got rid of that ages ago. If she was the villain, the missing thing a poison to lick like Snow Whites deep red apple. It would be nice to know how ironic Edwards letter really was.

But though she prepared herself, she kept forgetting, did not read, and in time believed her failure was a completed event. This made her both defiant and ashamed until she got a card from Stephanie a few days before Christmas, with a note from Edward attached. Hes coming to Chicago, the note said, December 30, one day only, staying at the Marriott, hope to see you then. She was alarmed because hed want to talk about his unread manuscript, and then relieved to realize there was still time. After Christmas: Arnold her husband will be going to a convention of heart surgeons, three days. She can read it then. It will occupy her mind, a good distraction from Arnolds trip, and she neednt feel guilty after all.

Anticipating, she wonders what Edward looks like now. She remembers him blond, birdlike, eyes glancing down his beaky nose, unbelievably skinny with wire arms and pointed elbows, genitals disproportionately large among the bones. His quiet voice, clipped words, impatient as if he thought most of what he was obliged to say were too stupid to need saying.

Will he seem more dignified or more pompous? Probably he has put on weight, and his hair will be gray unless hes bald. She wonders what hell think of her. She would like him to notice how much more tolerant, easygoing, and generous she is and how much more she knows. She fears hell be put off by the difference between twenty-four and forty-nine. She has changed her glasses, but in Edwards day she wore no glasses at all. She is chubbier, breasts bigger, cheeks rosy where they were pale, convex where they were concave. Her hair, which in Edwards day was long straight and silky, is neat and short and turning gray. She has become healthy and wholesome, and Arnold says she looks like a Scandinavian skier.