Menninger - The crime of punishment

Here you can read online Menninger - The crime of punishment full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1971, publisher: New York : Viking Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

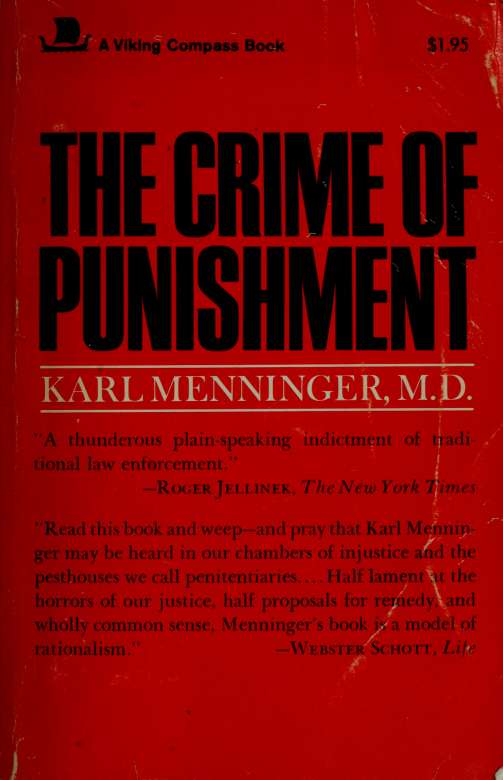

- Book:The crime of punishment

- Author:

- Publisher:New York : Viking Press

- Genre:

- Year:1971

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The crime of punishment: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The crime of punishment" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The crime of punishment — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The crime of punishment" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

The Human Mind / Man Against Himself / Love Against Hate Theory of Psychoanalytic Technique / A Psychiatrist's World Manual for Psychiatric Case Study / A Guide to Psychiatric Book_s The Vital Balance (with Martin Mayman, Ph.D., and Paul Pruyser, Ph.D.)

THE CRIME

OF PUNISHMENT

by Karl Menninger, M.D.

NEW YORK 1 THE VIKING PRESS

Preface

In 1924 two well-born Chicago boys conspired to kill an un-oflFending younger friend for no obvious reason. Partly just because the crime seemed so senseless, and partly because the families could aflford to pay for their services, many prominent American psychiatrists were brought into the limelight of the trial to explain the state of mind of the offenders. These colleagues were arraigned against one another; the opinions sworn to by some were flatly contradicted and denied by others.

This awkward and inconclusive exhibition gave rise to widespread public comment. It came at a time when in fields other than the law, psychiatry was leaping into a new prominence and promise of usefulness. The outpatient clinic had been created, neoars-phenamine had been discovered, psychological tests were being developed, the child guidance cUnic had been born, and psychoanalysis and other forms of psychiatric treatment were inspiring new hope in a field long characterized by cheerlessness and despair. It seemed appropriate, therefore, to WiUiam Alanson White, then president of the American Psychiatric Association, to appoint a special committee of that organization to study the relations of psychiatry and psychiatrists to the law and lawyers, to crime control, and to court procedure. To my great surprise. Dr. White appointed me chairman of that committee, and from my experience

fv'ith its studies I grew increasingly interested in the fields of criminology, penology, and jurisprudence, especially as they involved the discipline of psychiatry. In theory, there would seem to be an intimate connection; in practice, the gulf is very wide.

Many distinguished colleagues joined and succeeded me on this committee over the years to follow. Two of the most active were my friends Dr. Gregory Zilboorg and Dr. Winfred Overholser, and it was largely through their efforts that special funds were obtained from an anonymous giver, since identified as the Aquinas Foundation, for an annual prize entitled the Isaac Ray Award. This was to be given to a psychiatrist or jurist of some attainments in his field who would undertake a series of lectures on the subject of medical-legal relationships at a university where there was both a law school and a medical school. The first award was given in 1952 to Dr. Overholser, and subsequent awards were given to Gregory Zilboorg, John Biggs, Henry Weihofen, PhiHp Q. Roche, Manfred S. Guttmacher, Alister W. MacLeod, Maxwell Jones, David Bazelon, and Sheldon Glueck.

In 1962, when I received the Isaac Ray Award, Columbia University was selected for two of the lectures, which I gave on December 5, 1963, and April 14, 1964. The third lecture was given at the University of Kansas on April 14, 1966, as a part of its Centennial Anniversary. This book is an expansion of those presentations.

When it came time to select a theme for these lectures, I found myself with an embarrassment of riches from which to choose. I reflected long and hard on the question: Just what is the problem that we are concerned with? Is it that so many crimes are committed in spite of our increasing degree of civilization? But is the incidence of crime actually or even relatively increasing? Is the problem the fact that relatively few offenders are caught? Or that they are not convicted? Or that we don't know what to do with them when found guilty? Is it that lawyers and psychiatrists don't get along or come to any agreement regarding the psychology of crime ? Luck, today, seems to decide whether an offender goes to a doctor or to a prosecutor; is this proper? Is it possible to call crime

Preface \ vii

\ sickness when we know that most crimes are not committed by criminals but by ordinary citizens who lift goods off supermarket shelves ?

What, then, really is the crime problem? Each one of us wants the highest possible degree of physical safety. We all want freedom of action, but since some people abuse this privilege and impair our freedom we have had to set up some rules to keep the King's Peace. Long ago this was done; the King set them up, and we have accepted them and restated them in our terms. In substance it was agreed that we shall each have our freedom under God and the King and the law; but

Certain people, ideas, beliefs, conceptions, and social customs must not be treated with disrespect. (Others may be.) Certain persons must not be killed or injured. (Others may be.)

Certain persons must not be taken as sexual parmers, and certain methods of sexual gratification must not be indulged in. (Again there are exceptions.)

Certain objects must not be used or removed by others than the owners because they are someone else's property. (But one may borrow, and if one is powerful enough, one may take.) Certain services must not be demanded from servants, employees, or subordinates. These ambiguous stipulations and prohibitions were all tied up with penalties and sanctions for violation with intent {mens rea). A minor transgression is usually considered to be a private affair between the offender and the offended, and is regulated mainly by civil law. But a major crime injures not only the offended individual but the whole community; the social order itself is affected. The offender's management therefore becomes a public ritual of theatrical character. In a kind of medieval morality play, a villain is suspected, captured, exhibited, subjected to trial by ordeal, and duly executed or sent to the dungeons. This is to show the truth of the scripture that the wages of sin are death, and for centuries this was the wage commonly paid.

It is a well-known fact that relatively few offenders are caught, and most of those arrested are released. But society makes a fetish of wreaking "punishment," as it is called, on an occasional captured and convicted one. This is supposed to "control crime" by ^le-terrence. The more vaUd and obvious conclusionthat getting caught IS thus made the unthinkable thingis overlooked by all but the offenders. We shut our eyes Hkewise to the fact that the control performance is frightfully expensive and inefficient. Enough scapegoats must go through the mill to keep the legend of punitive "justice" alive and to keep our jails and prisons, however futile and expensive, crowded and wretched.

All this we have observed for years. Many of us have participated in this dumb show many times. Now that I was about to become a pubHc oracle, a spokesman for liaison between law and psychiatry, what should I declare about this social monstrosity? What should I emphasize or demand, remembering that I am not a poHtical scientist or a criminologist but only a psychiatrist?

Now, a cat may look at a queen, they say, and even a psychiatrist can see that the King's Peace system no longer works. Nor need one be a psychiatrist to know that our justice is anything but just for most of the people it is "appHed" to, and anything but efficient in protecting the rest of us from the rule-breakers. And since I have been watching all this for a good many years, I decided to talk about what I had seen and felt as a psychiatrist and citizen.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The crime of punishment»

Look at similar books to The crime of punishment. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The crime of punishment and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.