Harry Sword - Monolithic Undertow

Here you can read online Harry Sword - Monolithic Undertow full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Orion, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Monolithic Undertow

- Author:

- Publisher:Orion

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Monolithic Undertow: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Monolithic Undertow" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Monolithic Undertow — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Monolithic Undertow" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

for Tamara, Freddie, Jack and Lana Sword

Wed spent three days mainlining Duvel, Oude Geneva and ludicrously strong hydroponic weed.

The only solids to pass my lips were a couple of kapsalon kebabs Rotterdams infamous grease bomb, a mound of unidentifiable meat slurry topped with gouda shavings, chips and gloopy Dutch saus. A fellow writer and I were covering Roadburn Festival in Tilburg for the Quietus, and had spent the last few hours in communion with three thousand people standing stock still, head banging slowly in perfect union.

Its like the wailing wall in there.

In his dazed, half-hypnotised state, my friend perfectly captured the ritualistic power of doom metal done properly. Bongripper had just finished performing their aptly named Miserable LP in its entirety a slow-building endurance test of brute physical bass weight. By the time we stumbled into the clouds of weed smoke outside Tilburgs 013 arts complex (dubbed Freak Canyon by locals due to the bedraggled and often extravagantly bearded hordes of psychedelic warriors who descend en masse to the quiet university town each April) we were in a state of advanced sonic inebriation.

Bongripper play at heinous volume the kind that makes teeth rattle like stray dominoes and lungs disgorge forgotten matter. That the band look like trainees in a Sunday Times top 30 legal firm rather than grizzled doom veterans only adds to the sense of disorientation.

Roadburn is the worlds foremost pilgrimage for doom, drone and the outer church of noisy psychedelia: it champions the slow, the heavy and the weird. The festival is a serious proposition. Consider: Eyehategod New Orleans sludge forefathers, whose slow-motion beastings evoke some hellish opiate withdrawal in 100 per cent humidity playing in a consecrated church for two successive days.

Where a chilled Sunday afternoon lull in the programming is a screening of Dario Argentos opulent giallo bloodfest Suspiria, with its creepy score performed live by Italian proggers Goblin, sending those poor souls who had indulged too freely in fungal-based hallucinogens scuttling for the back doors. Over Roadburns four days, peals of feedback and sustain beat away at the years residual cortisone like some cathartic audio elixir resetting wayward strands of DNA. At times, it felt like I was experiencing the sonic embodiment of a palpable universal hum those onstage channelling a mighty audio portent as opposed to merely playing.

Music from the doom/drone continuum subverts traditional rockist tropes the preening machismo; the virtuosity; the cult of the performer; the adolescent turbulence leaving a bare-bones structure of primal catharsis. Chords that last a full half-hour, a maelstrom of feedback, a Jah Shaka-esque bass blanket that shakes the bodily foundation. And though ostensibly dark and physically oppressive the music of Sunn O))), Electric Wizard, Saint Vitus, Melvins, Neurosis, Sleep or Earth is about more than that. For me, these are agents of primordial sonic ablution, enablers of psychic transferral to a different mental plane: a punch-drunk station of gleeful oneness, a place to embrace your inner medieval psychedelic pieman or switch off the mind altogether. Records like Sleeps Dopesmoker or Neurosis Through Sliver in Blood carry a sense of ritualistic power: you dont listen; you partake in sonic ceremony.

Sitting in the Cul De Sac, Roadburns smallest venue and one of Hollands finest dive bars where sweat drips from the low ceiling and the air is scented with creaking leather the seeds of this book were formed. I was, initially, going to map the story of doom metal and its many satellites. A deeply underground affair until the mid 1990s, this scene was now a worldwide cult with the attendant infrastructure dedicated record labels, magazines, promoters and festivals that entails. Roadburn feels like a family of fervent believers. It struck me as odd that nobody had told the story of the music.

As I began to think more deeply, the idea of a straight-up history of doom felt reductive. Doom metal is, after all, defined primarily by the use of extreme sustain. The drone, in other words. And the drone is found everywhere from Buddhist chant to Indian raga; free jazz to ambient techno; minimalism to industrial, not to mention the myriad drones of nature. It can underpin music as (seemingly) disparate as the crackling dub techno of Basic Channel, the ecstatic jazz of Alice Coltrane or the oppressive glory of Godflesh.

Its amorphous nature, capacity for assimilation into unlikely spaces and presence in musical traditions around the world presented an intriguing ley line. As I researched the idea of the drone, its recurrence throughout musical history and place in theology and philosophy alike, I started to consider why we seek immersion in slow-moving sounds. What had begun as a hazed pondering in a nicotine-stained Dutch bar had become a quest to understand the essence of the drone both how it came to underpin such diverse forms of music and why people have been drawn to it for millennia.

Speed in music reflects change. Societal, personal or political. Disruption to an established order. In the 1950s, teenagers ripped cinema seats with flick knives as society looked on aghast at the onset of rock n roll delirium. Young blood, pumped on the adrenalised key hammering of Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis et al. Fast-forward twenty years and we find punk marshalling amphetamine drive in evocation of nihilistic oblivion, political unrest and frequently both. Electronic dance music has frequently presented a similarly confrontational stance, be it drum and bass pushing a frenetic 170 beats per minute in the name of urban futurism or Detroit techno evoking the ravaged topography of the (former) motor city a husk of staggering decrepitude reverberating to Underground Resistance.

But while velocity in music is readily associated with unrest, the left-hand path slow-moving hypnotic sound is a road far less travelled, at least critically. Monolithic Undertow explores the viscous slipstream drone, doom and beyond and claims the sounds uncovered, which hinge on hypnotic power and close physical presence, as no less radical. It is not, however, a history of drone as genre. Once genre lines become codified, the least interesting music happens. As Birmingham techno producer Surgeon once put it to me: That thing of when people say: Right then, today, Im going to make a dark techno track. That attitude is the absolute recipe for shit music. Its looking at music on the pure surface level.

So it is with all music.

Instead of gravitating to genre, this book follows an outer stellar orbit of sounds underpinned by the drone. The bulk of the narrative is concerned with the twentieth-century underground, and how so much of it came to be shaped by the drone. I was also keen to include substantive background on the vital influence of non-Western musical traditions. Too often the importance of Indian classical music, say, is relegated to a footnote or brief paragraph in discussions of the wider sixties rock lineage. But as well see were it not for the enduring influence of figures like Ravi Shankar or Pandit Pran Nath the underground landscape of today would be completely unrecognisable.

Certain topics covered in early chapters archaeoacoustics, the ecology of background noise, the spiritual trance traditions of India and Morocco, the role of sound in Dionysian ritual could, of course, fill many books, many times over. My hope here was not to comprehensively catalogue such venerable traditions and areas of deep scholarship, but to open potential wormholes in the minds of curious readers, and link areas that may otherwise have remained disconnected.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

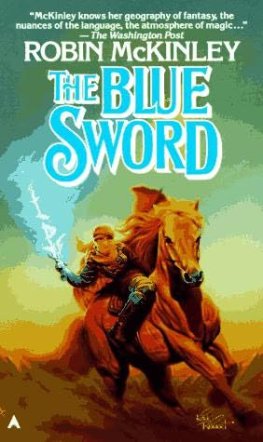

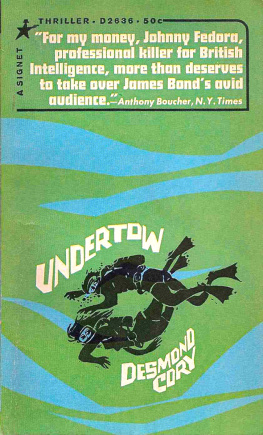

Similar books «Monolithic Undertow»

Look at similar books to Monolithic Undertow. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Monolithic Undertow and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.

![J K Rowling - Harry Potter [Complete Collection]](/uploads/posts/book/117015/thumbs/j-k-rowling-harry-potter-complete-collection.jpg)