INTRODUCTION

Wonder and Resistance

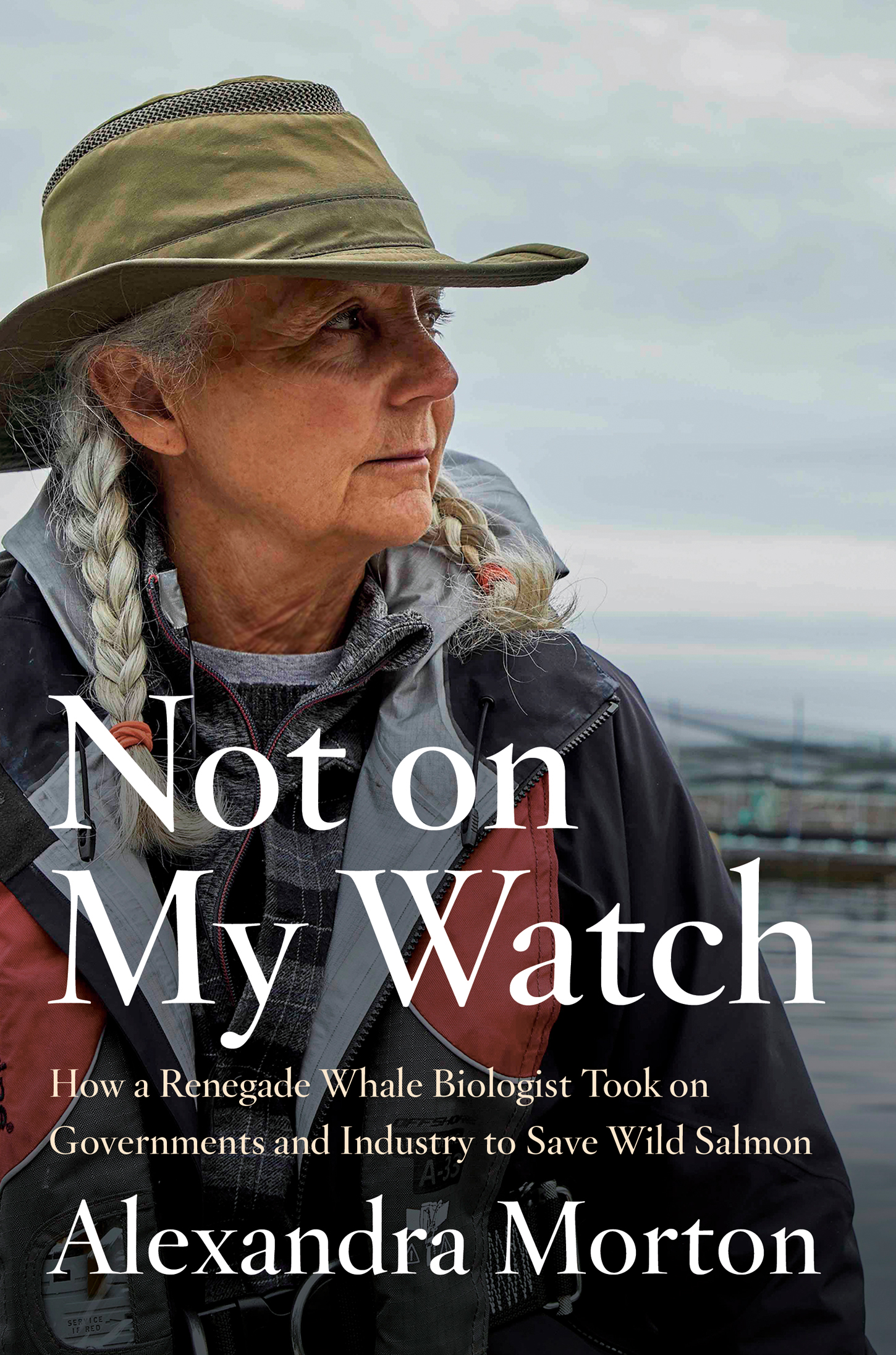

WHEN I WAS a child I was drawn to animals, especially the wild ones, and to the ponds and forests where they lived. I was curious. I tracked them and watched them. No matter whether I was looking into the gold-flecked eye of a frog, or at the way a deer held her ears as she stepped out of the forest at sunset, animals were mysterious, beautiful and wise. When I turned eight, I knew wanted to become a scientist but I wasnt sure how. The only picture of a woman scientist that I had seen was of Madame Curie, and I was afraid to become that person in the blurry picture wearing a white lab coat. At the same time I realized that only small children played with animals. A growing dread consumed me. To grow up I needed to stop spending time in the woods and marshes. I still remember the sensation of stopping myself from looking under a piece of wood where I knew a snake almost certainly lay coiled.

Then just before Christmas 1965, I received an issue of National Geographic with Jane Goodall on the cover. I stared at it. The outer world paused and went silent as I sank to the dark brown carpet of my mothers study. I pored over every picture of this beautiful woman, looking perfectly happy, who studied chimpanzees in the frightening jungle. Was she real? I felt an explosion of joy as the walls I was building around myself crumpled and the inner compass I was trying to redirect slipped free. I would follow in the footsteps of Jane Goodall. That was my promise to me. Seeing those pictures of Jane gave me my life. Thank you so much, Jane, for allowing National Geographic to expose your work and your paradise, no small sacrifice, I realized years later.

Over the next decade, I read every book about scientists who, following in Goodalls footsteps, went into the wilderness to study an animal. And I saw a pattern. While they began as people driven by curiosity and the need to understand, they inevitably became activists, though none of them used that term back then. The more they understood the animal they had chosen to study, the more urgently they felt the need to stand in the way of the crushing advance of human appetite for the land on which the animal relied or for the creature itself. I felt sad for these scientists. They had to abandon the dream they had worked so hard for. They had to leave the jungle, savannah or ocean to confront the people who were causing the damage. Once the scientists found the perpetrators, they had to figure out how to stop them.

Dr. Jane Goodall did more than reveal the origins of our humanness through her science; she demonstrated that becoming a groundbreaking scientist didnt require a loss of compassion. Other scientists criticized her heavily from the start for giving the chimps she was studying names instead of numbers. Today she admits in her lectures that she went into a conference on primates a wildlife biologist and came out an activist, when she refused to accept the methods of her colleagues, who, in the name of science, were torturing primates in a way that horrified her.

I took this all in and decided I was not going to be shoved off my lifes path. I was going to plug my ears, ignore the issues and follow my dream to the end. I was going to decipher the language of some large-brained non-human species, creating a Rosetta stone of sorts to end the solitude of my species. We needed to hear what another animal on this planet was saying, I thought, because it seemed that we were going mad in our isolation. A lofty aim for a teenager, I know, but this is what I wanted to do. Of course things are so much simpler when you are a child, and so I failed to stay true to my fifteen-year-old self. What I didnt realize back then was that if I ignored the impact humans were having on the animals I had chosen to study, I would end up studying their extinction.

It gets even more complex. Scientists who go to learn about animals in the remote regions of our planet also meet Indigenous people. While the peoples and cultures that evolved over thousands of years in one place are adapted to their home environment, the scientist is, in many ways, an introduced species.

When I first arrived in the remote archipelago on the west coast of Canada, where I still live, to study whalesmy chosen large-brained mammalI didnt understand the land, the animals or the people. I had no idea how to respond to storms or predators or where to find food. I didnt immediately recognize the difference between the nomads of the planet, meaning people who moved generation after generation, and the people who spent thousands of years in one place. Over the years I have encountered instances where my Indigenous companions have heard and felt things I dont. Asking them questions didnt help. I was simply not adapted to the place and did not have the internal hardware to perceive some things.