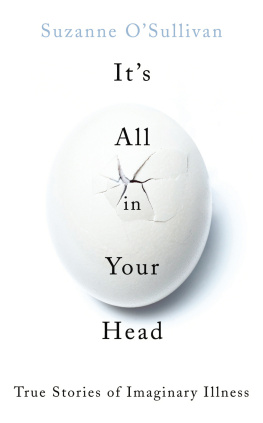

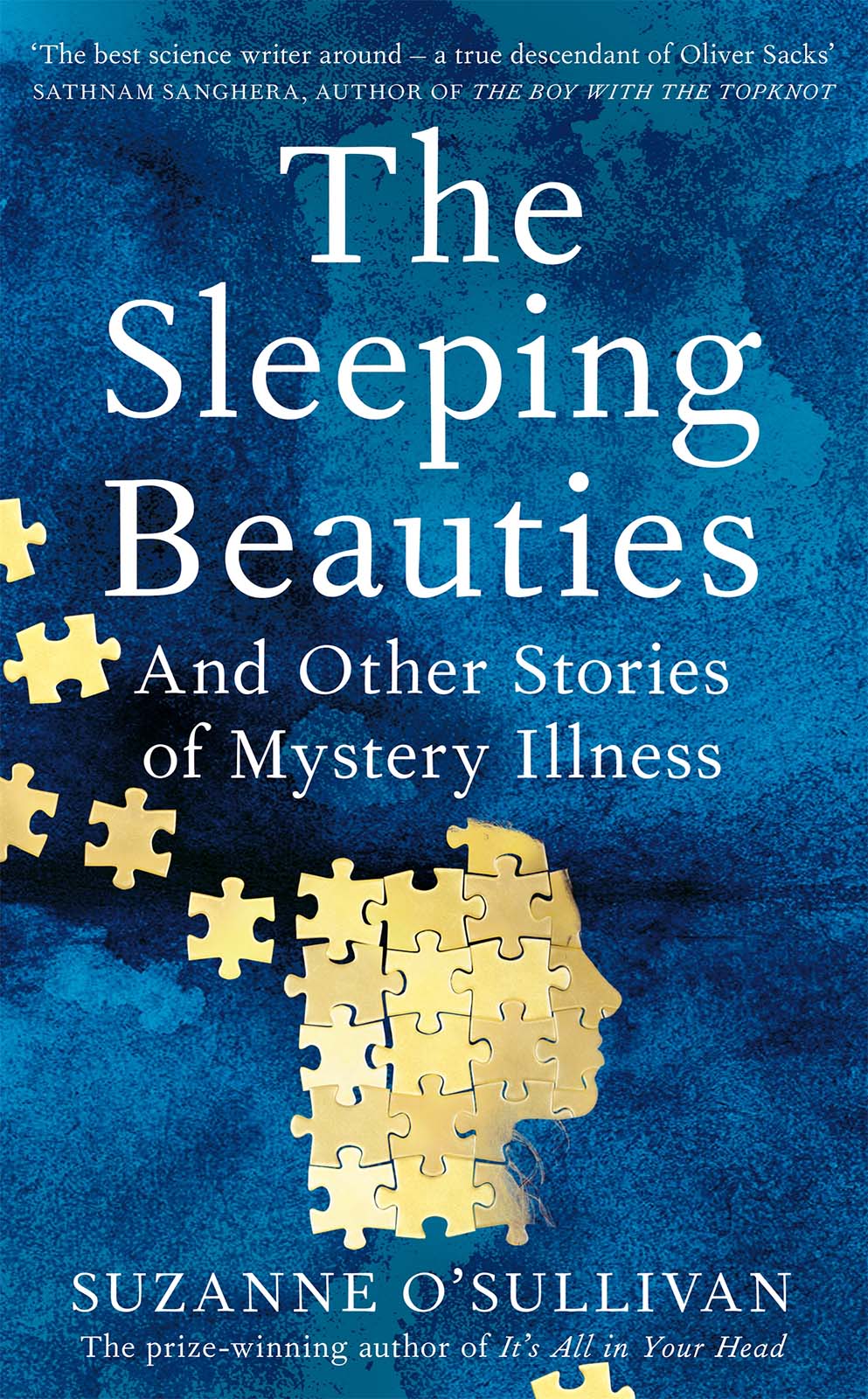

The Sleeping Beauties

And Other Stories of Mystery Illness

SUZANNE OSULLIVAN

To try to understand the experience of another it is necessary to dismantle the world as seen from ones own place within it and to reassemble it as seen from his.

John Berger, A Seventh Man, 1975

Contents

Preface: The Mystery Illness

Mystery: Anything that is kept secret or remains unexplained or unknown.

I first heard about it from a news website in late 2017. The article, headlined Swedens Mystery Illness, told the story of Sophie, a nine-year-old girl who had fallen into a lifeless, unresponsive state more than a year before. Sophie couldnt move or communicate. She couldnt eat or even open her eyes. In fact, for a very long time, all she had done was to lie completely still, showing no indication of knowing day from night.

The article included a picture of Sophie. It showed her wrapped in a pink blanket. Pinned to the yellow striped wallpaper behind her were a childs drawings hers, probably, from an earlier time. She was not in hospital. This was her own bed, in her own bedroom. Despite her unresponsive state, medical tests suggested that her brain was healthy. Rather than explaining the coma, her scans said she was not in one at all. With nothing to actively treat, the doctors had sent her home to be cared for by her family, and there she lay, many months later, getting neither better nor worse.

Although the headline made it sound as if Sophies illness was a complete enigma, the body of the article suggested that the cause was not entirely unknown. Sophie had entered Sweden as an asylum seeker. In her home country of Russia, her family had been subject to persecution by the local mafia. Sophie had seen her mother beaten and her father seized by police. Her illness had started very soon after she and her family had fled Russia and entered Sweden. With good reason, her doctors assumed that the illness had a psychological cause.

As a neurologist, I am familiar with the power of the mind over the body more than most doctors, perhaps. I regularly see patients lose consciousness through a psychological mechanism rather than as a disease process. I would not consider this phenomenon to be at all rare, or even unusual. At least a quarter of those referred to me with seizures, many of whom believe they have epilepsy, prove to be suffering from dissociative, or psychosomatic, seizures. Those high numbers are not specific to my clinical practice. Up to a third of people attending any neurology clinic have a medical complaint that is likely to be psychosomatic in nature meaning real physical symptoms that are disabling, but which are not due to disease and are understood to have a psychological or behavioural cause. Paralysis, blindness, headache, dizziness, coma, tremor, or any other symptom or disability one can imagine, has the potential to be psychosomatic. And, of course, its not just a neurological phenomenon; any organ in the body can be affected and almost any symptom can be generated in this way skin rashes, breathlessness, chest pain, palpitations, bladder problems, diarrhoea, stomach cramps, and on and on.

Despite the ubiquitous nature of these disorders, many people still doubt them, considering them somehow less real than other sorts of medical problems. I admit, I struggle to see where this underestimation comes from. I am aware of all the ways in which my own body speaks for me, often unbidden. My posture changes with my mood. Poorly controlled facial expressions inadvertently reveal my opinion to others, even when I dont intend it. It doesnt seem a stretch, therefore, to suggest this embodiment of a persons inner world has the potential to extend into illness. That the body is the mouthpiece of the mind seems self-evident to me, but I have the sense that not everybody feels the connection between bodily changes and the contents of their thoughts as vividly as I do. So, when a child becomes catatonic in the context of stresses of the most extreme sort, people are amazed and perplexed.

Perhaps it is not so surprising that the general population undervalues psychosomatic disorders, if you consider for how long they were neglected by doctors and scientists. For most of the twentieth century, neurological psychosomatic disorders, under the names hysteria and conversion disorder, were still viewed through a Freudian lens. In Studies on Hysteria, his seminal work on the subject, Freud imagined the seizures, paralysis and various disabilities of hysteria as arising from hidden psychological trauma, which is then converted into physical symptoms. For example, a woman too frightened to express herself might suppress the source of her fear, and in so doing lose the power of speech. In Freuds formulation, every symptom could be tracked back to a specific moment of psychological torment. That viewpoint had such traction that, even today, many people, including a large number of doctors, still regard repressed trauma and denied abuse as the full explanation for all psychosomatic disorders. This has created decades-long counterproductive relationships between doctors and patients, in which the doctor insists that their patient is in denial about an unresolved conflict and the patients subsequent refusal to accept that viewpoint only goes to prove the doctors point.

The stagnation of scientific progress in the field of psychosomatic disorders left lots of room for a mystery narrative to develop. How is it possible for someone to fall into a coma when their brain seems perfectly healthy? What causes the leg paralysis of a psychosomatic disorder if the nerve pathways are all intact? How does that ethereal thing, referred to as the mind, cause seizures? In fact, in the twenty-first century, a considerable amount of work has gone into answering these sorts of questions. In the field of neurology, psychosomatic disorders have become an area of great interest, resulting in a rapid growth in research on the subject. In the scientific world, at least, the one-dimensional concept of stress converted into physical symptoms has been debunked and replaced by more sophisticated explanations. The problem is that these advancements havent yet made their way very far beyond specialist doctors and patient groups, into the wider public conversation.

What was once called hysteria is now referred to by some as a conversion disorder, or, more recently and more aptly, as a functional neurological disorder (FND). In most medical specialties, the term psychosomatic is still used to indicate medical problems in which the bodily symptoms are thought to have a psychological cause. However, in neurology, the word functional has increasingly replaced psychosomatic. Functional is considered preferable because it indicates that there is a problem with how the nervous system is functioning, while disposing of the prefix psych, which is too often (wrongly) distilled to mental fragility, or even madness, in peoples interpretation. Functional implies a biological problem, but without the assumption of the presence of stress that has existed in all previous versions of these types of disorders. It leaves open the possibility that emotional trauma is not the only means by which psychological processes can affect the functioning of the brain to lead to disability.

Both psychosomatic disorders in the realms of general medicine and functional neurological disorders in neurology are incredibly common and have the potential to be very serious medical problems. Yet people arent always aware of that, because, in the public arena, they can be very hard to spot, hidden as they are behind euphemisms, clichs and misunderstanding. That is aptly demonstrated by FNDs media portrayal, where it is commonly referred to as a medical mystery.