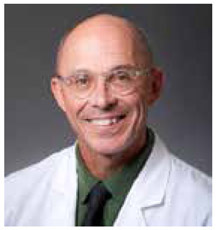

Rowland G. Hazard, MD, recently retired from a 30-plus-year career devoted to people disabled by chronic back pain. Currently Emeritus Professor of Orthopaedics at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, he is a physician, internationally respected scholar and researcher, widely published author, teacher, inventor, entrepreneur, athlete, and jazz musician.

As a clinician and director of functional restoration programs (FRPs) at the University of Vermont (19862000) and at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (20022018), Dr. Hazard cared for several thousand patients with back pain and led FRP teams of physicians, psychologists, physical and occupational therapists, and trainers. A board-certified internist, he is a fellow in the American College of Physicians.

He has published more than 50 journal articles and book chapters and delivered scores of related academic lectures and media appearances in the United States, Europe, and Australia. He has served as reviewer and technical expert for the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. A reviewer for several medical journals, Dr. Hazard sits on the editorial boards of Spine and The Back Letter. Elected to membership in the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine in 1988, he has twice served as U.S. representative to the Executive Council. Dr. Hazard lives in Vermont near the farm where he grew up.

Please send comments and suggestions for Talking Back to

.

WORKSHEET

MEDICAL CLEARANCE QUESTIONS

for you to answer with your doctor:

Do I have cancer, an infection, a fracture,

or any serious disease that requires treatment? ___yes ___no

Do I have a structural spinal problem

that requires surgery? ___yes ___no

Do I have a medical reason not to exercise? ___yes ___no

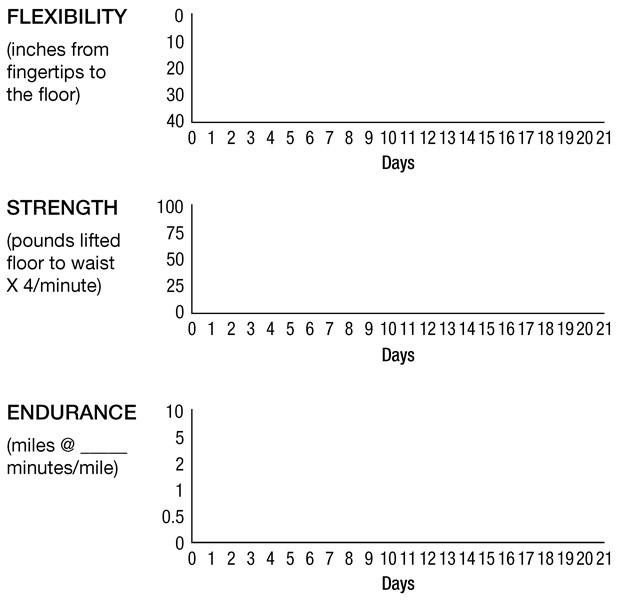

YOUR 4-MONTH GOALS

PHYSICAL REQUIREMENTS

FLEXIBILITY STRENGTH ENDURANCE

WORK

RECREATION

DAILY ACTIVITIES

TRAINING CHART

I magine that you are sitting at a conference table with six other people. You have been told that they have all suffered from back pain for at least 3 months, most of them for a matter of years. You will learn that these men and women come from various walks of life, but they have in common the reason they are there: pain severely limits their work, play, or activities of daily living. They are disabled, though you would not know that by looking at them. They have had all kinds of tests and imaging. They have tried everything to fix their pain, including injections, pills, surgeries, manipulation, acupuncture, hanging upside down, exercise, restyou name it. Strangers who have only just met, they are getting started in an intensive all-day, 3-week rehabilitation experience called the functional restoration program (FRP).

ROBERTA

First, meet Roberta, sitting on your right; more like perching on the edge of her seat. She gets up from time to time to stand and lean forward, supporting herself with her elbows on the back of her chair. You struggle with whether to ask her if there is anything you can do for her, but you dont. No one else does, and you are not sure yet how to behave in this group. Hold on to that uncertainty. You will see how important it is in a few minutes.

Roberta is a wispy-thin 35-year-old former loan officer with a pink streak in her platinum hair and not enough mascara to hide the depression in her eyes. You will learn that she is a single mother of four school-age kids and that she had always depended on exercise to curb her anxiety and dark moods. She never had what you would call an injury, but when she developed back pain, she couldnt tolerate long hours of desk work. She lost her job at the bank and, on a neighbors advice, stopped going to the gym. After 2 years of tests and treatments of all sorts, her savings dwindled. She told the kids they would have to move to an apartment in a more affordable town. She broke down in her doctors office, finally admitting to another person her hopelessness and fear of destitution. Little comfort and no plan came from the response, Im sorry, but we just dont know whats wrong with you.

A large whiteboard hangs on the wall with colored markers in the tray. I walk in and introduce myself. Taking off my hospital coat and MD badge, I sit down and explain that this is my favorite part of the program. I get to put aside my doctor role and all the expectations that may go with it. My plan is to share with these patients ideas that have come from meeting with groups like theirs over many years. Most of the ideas come from stories of previous FRP patients; the rest are carefully researched answers to their questions. Many of the ideas would surely raise the eyebrows of established medical practitioners.

Why do I trust in these ideas? Because they come from so many different people with such a variety of clinical and personal problems, consistently asking the same questions and reaching the same conclusions. Over the years, their stories and questions have fashioned these themes of personal wisdom like beating pieces of metal into practical tools.

To clarify who has the most firsthand experience with pain, I ask how long each person has had his or her current problem. The answers typically range from 6 months to 20 years, the average total for the group almost always topping 50 years. Fifty years! That is far longer than my 30 years of taking care of people in pain. So rather than me lecturing them on what is wrong with them and how to solve all their problems, it makes sense to pool our knowledge and to address together their personal situations and questions.

PAIN TALK

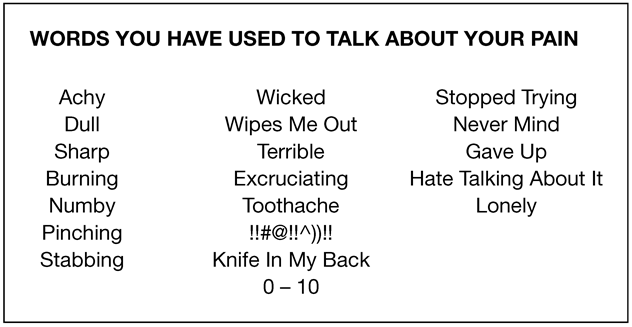

Stepping up to the board, I ask what words they have actually used to talk to other people about their pain. I write the words on the board in three columns. shows a typical list. I try to give everyone plenty of time, especially the apparently shyer members. Often, they encourage each other, and there are bursts of approval and recognition in response to the words they use in common, but there is a certain tension brewing. When the group runs out of words, there always comes a heavy silence. I let it linger long enough so that the group clearly becomes uncomfortable.

Figure 1.1.

What is going on here? Fifty years, and this is all you got? Then the emotions roll out, reflecting the frustration and resignation in column 3 on the right. It is unusual not to have both tears and expletives. To everyone, the most striking point made by the list is how short it is and how members of the group vary widely in the number and complexity of their personal terms. This is new territory for all. Almost none of them has ever discussed the challenge of talking about their pain and feeling so not heard.

When I ask the group about the purpose of the words in column 1, they respond that these are describing the quality of their pain. So why would you bother to describe how your pain feels to another person? In general, you want the other person to understand what is wrong with you, but that understanding depends on who that person is in crucial ways. First, if the person is a family member or acquaintance without medical training, you hope that he or she will grasp the nature of your pain so that he or she will know how to behave around you. If you have cancer or another serious disease, sympathy and physical assistance might be appropriate. If its just a strain and quick recovery is expected, the person might simply be encouraging or dismissive. Ever come home from an emergency room visit and have to tell someone that the pain that was severe enough to call an ambulance was just a strain? Try that for an exercise in humiliation. Guess what kind of reaction you will get from your boss if the back pain that has kept you out of work for 6 weeks is nothing serious, according to the doctor.