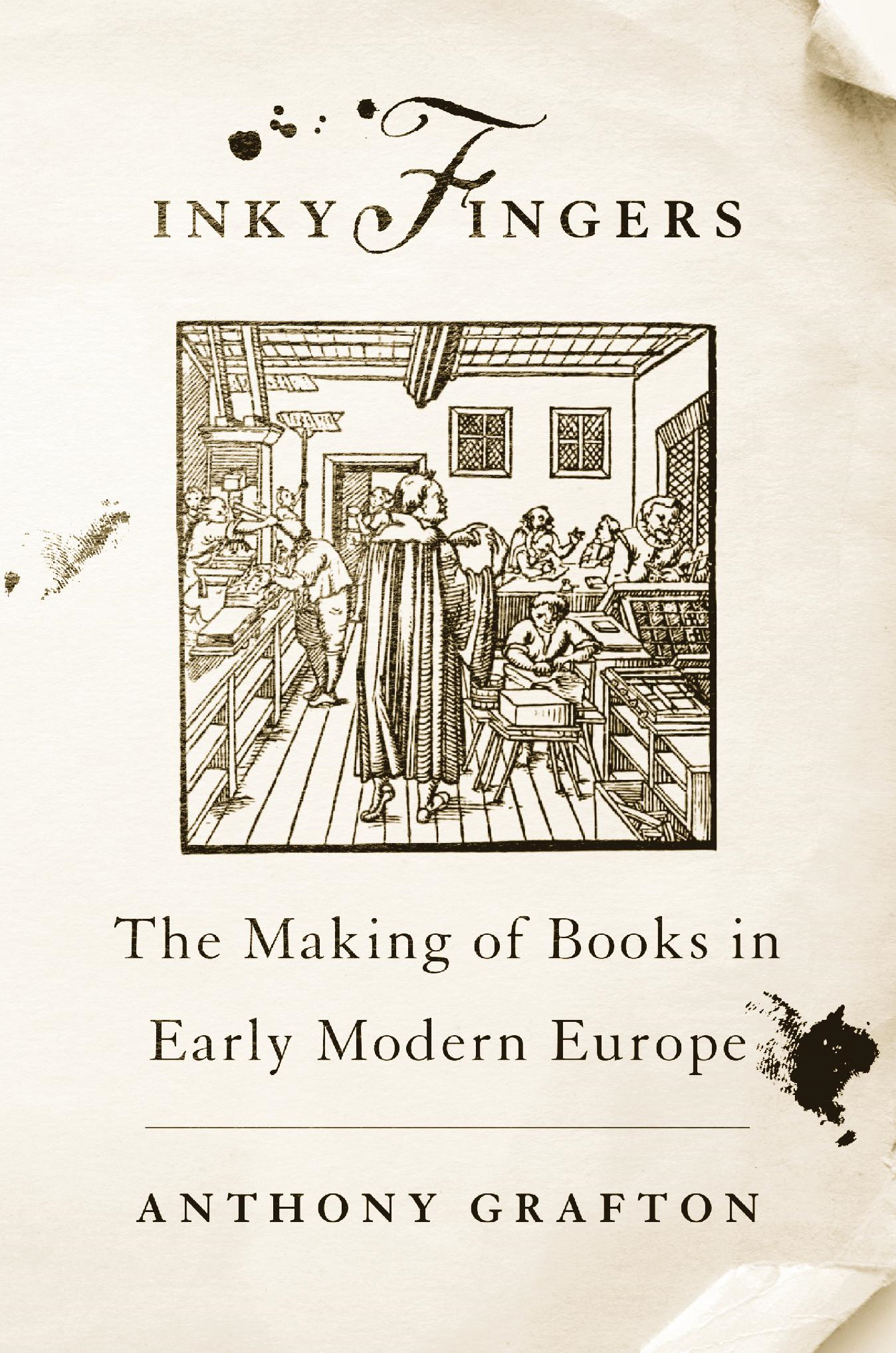

Cover art: Background, Getty Images; Inset, Illustration of a printers shop from Jeremiah Hornschuch, Orthotypographia, Leipzig, 1608

Names: Grafton, Anthony, author.

Title: Inky fingers : the making of books in early modern Europe / Anthony Grafton.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Subjects: LCSH: Early printed books. | BooksHistory. | HumanistsEuropeHistory. | PrintersEuropeHistory.

SCISSORS, PASTE, AND BEST-SELLING ETHNOGRAPHY

I N 1517, a German humanist named Joannes Boemus set out to make a book: a comprehensive ethnography of Africa, Asia, and Europe. A scholar of modest attainments, he knew neither Greek nor Hebrew. No great traveler, he lived in the free imperial city of Ulm, deep in the center of the Holy Roman Empire, where he served as chaplain to the Teutonic Knights. Why did this brief compendium, obsolete on its publication day, become a best seller?

Modern scholars have pointed to Boemuss method. By his own account, it was as traditional as the organization of his book. For three years, Boemus told his publisher, Siegmund Grimm, he had gathered material systematically from many outstanding writers. This was, in fact, his works chief claim to fame. It deserved credence because it rested on the best sources. Boemus expanded on this point in his preface, in which he described his work as an exercise in the deft use of scissors and paste:

In my leisure hours, O most serious connoisseur of histories, I have gathered, and then written out in this register, the more remarkable customs, rites, and laws of the peoples, and the places they inhabit. These were commemorated in passing and, as it were, in pieces by Herodotus, the father of history; Diodorus Siculus, Berosus, Strabo, Solinus, Pompeius Trogus, Ptolemy, Pliny, Cornelius Tacitus, Dionysius Afer, Pomponius Mela, Caesar, Josephus, and, from the more moderns, Vincent, Aeneas Silvius who later took the name Pius II, Antonius Sabellicus, Iohannes Nauclerus, Ambrosius Calepinus, Niccol Perotti in his Cornucopiae and many other famous writers. This will allow you to have them recorded in a single book, and it will be easy for you to find them when you need them.

Writing with confidence and pride, Boemus characterized his work as a patchwork of passages taken from earlier writers. He treated the bookish origins of the knowledge he offered readers as a major selling point. And the proud author was not alone: his friends agreed that a collage of texts, selected from established authorities and systematically organized, made a fine book. Short Latin poems by Boemuss friends preceded his preface. They highlighted the great care with which he had copied his material from the books of the authors. Most modern readers have adopted these terms in describing Boemuss book.

Boemus declared that he preferred this traditional, bookish method to the newer one, supposedly founded on eyewitnessing, that recent travel writers had adopted. In his prefatory letter to Grimm, Boemus remarked that his publisher had specialized in literature on foreign nations. In the preceding year alone Grimm had printed Maciej Mieochwitas treatise On the Two Sarmatias and Ludvico di Varthemas work On the Southern Peoples: recent works that described parts of the world previously little known to Latin Christians. One could attain such knowledge by travel, but one could also gain it by systematic reading.

And there was the rub. Grimms readers needed him to publish reliable texts, not the work of fly-by-night tricksters, nor that of wandering beggars, who make it their practice to lie criminally and without shame to make themselves popular and admired with the crowd. Their lies had made prudent readers distrust all writers who dealt with foreign parts. But they had also created a readership for what Boemus could offer: a panorama of the lands and cultures of the world, based on sources so old that they deserved credenceso much, apparently, for Varthemas vivid, challenging account of the Middle East and South Asia (based for the most part on first-hand experience), which Boemus did not excerpt. Like Boemus, his readers deliberately turned away from the potential challenges of new knowledge about the world outside Europe.

Boemuss practices as an author, as he and his associates described them, strikingly resemble those of Ordralphabtix, the fishmonger in the imaginary village of Astrix the Gaul. Obdurately refusing to deal in fish freshly caught in the nearby ocean, Ordralphabtix sold only what the wholesale dealers in Paris shipped to him. But there was one salient difference between them. The Gauls old fish stank, and their stench caused fights. Boemuss extracts from old texts, by contrast, attracted readers as flowers attract bees. One way to make a salable book in the sixteenth century, apparently, was not only to construct it using scissors and paste, but also to take care that potential buyers knew that the author had done soin a few years, during his spare time.

In fact, Boemus, like many authors, misdescribed his own work. It was far more than a straight collection of excerpts from texts, and its conclusions were often as far from traditional as its methods. And that is why he claims our attention here. This book collects nine studies in the forms of scholarly authorship in Western Europe between the fifteenth and the eighteenth century. They re-create lost ways of writing and publishing, tracing the ways in which the material worlds of reading, writing, and printing affected texts and their reception. Watching Boemus handle his sources as he reads them, copies them, and transmutes them will help us frame and follow the larger set of inquiries that follow his story.

Im writing a book is a very suggestive phrase. Images immediately spring to mind: images of solitary creativity, pursued in a comfortable study, cozy caf, or bleak garret. None of them, as we will see, fit the world of the Renaissance humanists who are the protagonists of this book. Their life of scholarship could cramp the hands and buckle the back. Reading and writing were as closely connected in the age of the quill pen as they are in that of the laptop. Readers often worked, just as writers did, pen in hand, actively responding to the texts they read in their margins or eagerly chopping them into extracts for storage and reuse. Writers were as often copyists as composers, seeking, not to make it new, but rather to refashion what they had read in subtle but powerful ways, so that ancient writers could teach modern lessons. Making a bookor even mastering someone elses bookrequired hours of physical labor, carried out with strenuous attention, tongue in teeth. Often the most ingenious ideas and practices that they devised came into being less in silent study than in the course of what looks, in the age of the computer, like exhausting, unremitting work.