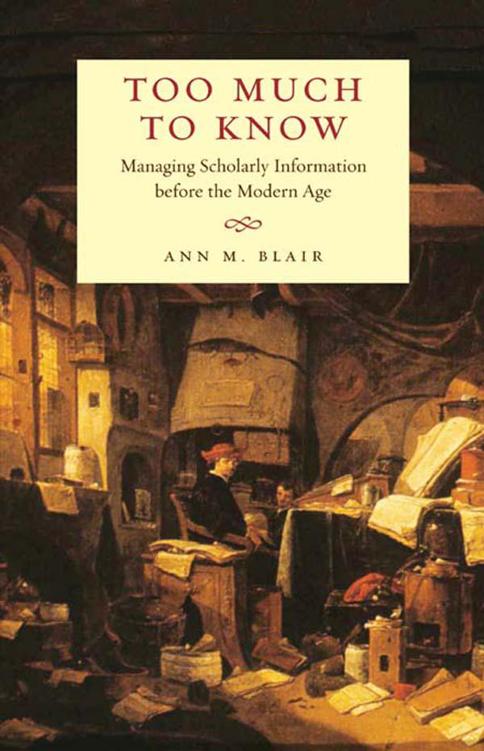

T OO M UCH TO K NOW

T OO M UCH

TO K NOW

Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age

Ann M. Blair

Yale

UNIVERSITY

PRESS

New Haven & London

Copyright 2010 by Yale University.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including

illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by

Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by

reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational,

business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail

(U.S. office) or (U.K. office).

Set in Electra type by Tseng Information Systems.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN: 978-0-300-11251-1 (cloth)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010024663

Catalogue records for this book are available from the

Library of Congress and the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ansi/niso

Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jonathan,

Adam, and Zachary,

who have filled

my life with much joy

C ONTENTS

L IST OF I LLUSTRATIONS AND T ABLES

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

One of the great pleasures of parting with a project long under way is the opportunity to thank the many people and institutions who contributed to the process and the outcome. The provinces I frequent in the international Republic of Letters, inhabited by intellectual historians, historians of science, and book historians of early modern Europe, are rich in creative and learned scholars whose suggestions and comments have been central to my thinking. Anthony Grafton has responded with unflagging acumen to my queries for over twenty years and commented on more than one iteration of this book, saving me from errors and opening new leads to explore. Ian Maclean generously read the bulky drafts of two chapters. David Bell contributed helpful insights at crucial points. Two readers for Yale University Press made excellent suggestions. I am grateful to the editorial and production teams at Yale University Press, especially to Lara Heimert for her initial enthusiasm and to Christopher Rogers for following through with equal supportiveness, to Laura Davulis and Margaret Otzel for their patient replies to many queries, and to Eliza Childs for superb copyediting.

My research, carried out over more than a decade, benefited from many invitations to speak. I am grateful to my audiences and hosts in Paris (thanks, on different occasions, to Annie Charon-Parent, Christian Jacob, Christian Jou-haud, and Laurent Pinon), Cambridge (Richard Serjeantson), Munich (Martin Mulsow), Gttingen (Gilbert Hess), Berlin (Lorraine Daston, Nancy Siraisi, and Gianna Pomata), and Zurich (Anja-Silvia Goeing), and at many American universities: Arizona State University, Bard Graduate Center, Boston College, Boston University, Brown, CalTech, the University of Chicago, Cornell, the University of Indiana, Johns Hopkins, Harvard and the Radcliffe Institute, McGill, New York University, the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton, Rutgers, Stanford, and the University of Wisconsin. I have received valuable feedback from other scholars at conferences as well, even if I cannot acknowledge them individually. Special thanks to Carlos Gilly for welcoming me into his home in Basel and sharing his immense expertise on Theodor Zwinger, to Urs Leu for his help in Zurich, and to Ian Maclean for facilitating so graciously a research trip to Oxford. I have enjoyed conversation and correspondence on many topics, but those on note-taking were especially exciting, notably with Peter Beal, Peter Burke, Jean Card (who first showed me the value of early modern reference works), Alberto Cevolini, Jean-Marc Chtelain, John Considine, Candice Delisle, Elizabeth Eisenstein, Max Engammare, Gilbert Hess, George Hoffman, Howard Hotson, Noel Malcolm, Peter Miller, Paul Nelles, Brian Ogilvie, Allen Reddick, William Sherman, Peter Stallybrass, Franoise Waquet, Klaus Weimar, Richard Yeo, and Helmut Zedelmaier. More specific debts are recorded in the notes.

This project has also led me into times and places distant from early modern Europe, and I am grateful to those who have guided me in fields in which I have no specialist expertise. Hilde de Weerdt first fielded my queries on Chinese encyclopedias some twelve years ago and commented on my sections on China; she and Lucille Chia have been the principal agents of my initiation into Chinese book history, including their invitation to participate in a conference in June 2007. My interest in Islamic topics was started by a conversation with Jonathan Bloom in 2000 and aided by Roy Mottahedeh, who invited me to a conference in 2003, and by conversations with Beatrice Gruendler in spring 2009; Elias Muhanna read the relevant section of my manuscript. Kathleen Coleman and Scott F. Johnson made valuable comments on my sections on antiquity and Byzantium, respectively. Brigitte Bedos-Rezak read the medieval sections; she and other medievalists, including Nancy Siraisi, Marcia Colish, Beverly Kienzle, John van Engen and the work of Richard and Mary Rouse, inspired me to delve into the Middle Ages more than early modernists usually do.

At Harvard I have enjoyed not only unsurpassed working conditions but also a congenial and supportive atmosphere in the History Department and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences more generally. I am grateful for conversations with many colleagues and for comments on drafts from Nancy Cott, Lani Guinier, James Hankins, Michle Lamont, Jane Mansbridge, Leah Price, and Harriet Ritvo. Many students, most of them from Harvard, have served as research assistants over the years, gathering books and articles and resolving particular problems. For taking on extra work in addition to their own projects I am grateful especially to Andrew Berns, Charles Drummond, John Gagn, Matt Loy (who constructed a draft of the bibliography), Charles Riggs, and Morgan Sonderegger, whose research in online library catalogs is presented in simplified form in the tables. Felice Whittum drafted permissions letters and did much of the indexing.

Warm thanks to all those who helped me in the many libraries where I worked, most notably: Universitatsbibliothek Basel, Zentralbibliothek Zrich, Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbttel, Staatsbibliothek Munich, Universitatsbibliothek Gottingen; the British Library, the Bodleian Library, the Cambridge University Library, and many college libraries in Oxford and Cambridge; and in Paris the old Bibliothque Nationale, the new BnF, and the Bibliothque Mazarine. I am grateful for correspondence to the archives of Kaysersberg (Alsace) and Savona (Italy), to the library of the Accademia dei Concordi in Rovigo (especially Michela Marangoni), and to the Biblioteca Universitaria in Bologna. Above all I am indebted to the staffs of Widener and Houghton libraries for their good cheer through many requests, often for very large books.