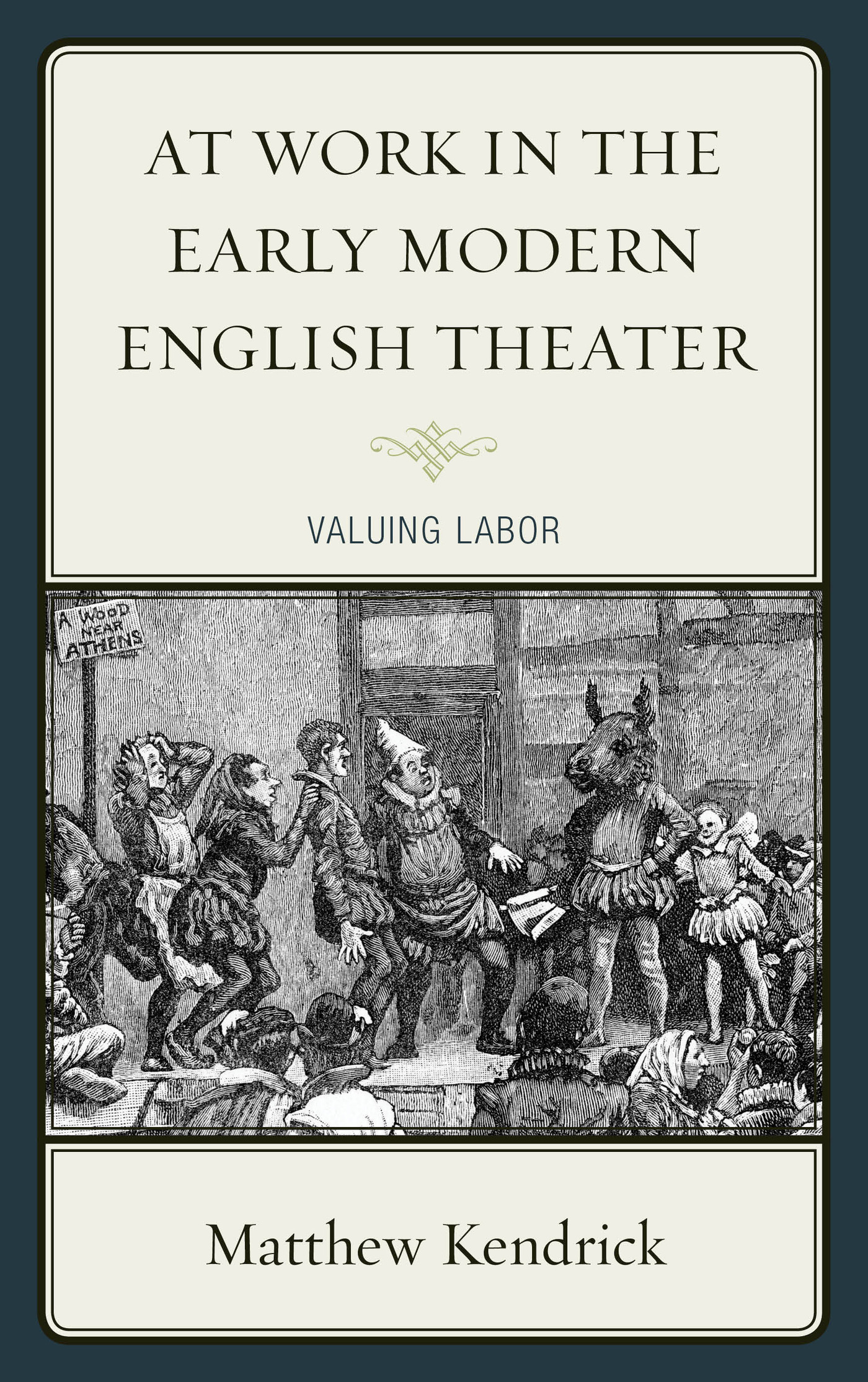

At Work in the Early

Modern English Theater

At Work in the Early

Modern English Theater

Valuing Labor

Matthew Kendrick

FAIRLEIGH DICKINSON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Madison Teaneck

Published by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press

Copublished by The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2015 by Matthew Kendrick

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kendrick, Matthew, 1982

At work in the early modern English theater : valuing labor / Matthew Kendrick.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61147-824-2 (cloth) -- ISBN 978-1-61147-825-9 (electronic)

1. English drama--Early modern and Elizabethan, 1500-1600--History and criticism. 2. English drama--17th century--History and criticism. 3. Theater--England--History--16th century. 4. Theater--England--History--17th century. 5. Labor in literature. 6. Labor movement--England--History--16th century. 7. Labor movement--England--History--17th century. I. Title.

PR651.K425 2015

822'.3093553--dc23

2015003364

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

Acknowledgments

This book began as my dissertation project at the University of Pittsburgh. Special thanks to John Twyning, Jennifer Waldron, and Nicholas Coles for their careful comments and guidance during the projects early stages. I also want to thank Rachel Trubowitz, who has supported and encouraged me every step of the way. Two sections of this book first appeared elsewhere: a section of chapter 1 first appeared as Humoralism and Poverty in Jonsons Every Man in his Humour, South Central Review 30, no. 2 (2013): 7390, and a section from chapter 4 first appeared as A shoemaker sell flesh and bloodO indignity!: The Labouring Body and Community in The Shoemakers Holiday, English Studies 92, no. 3 (2011): 25973. I thank these editors and journals for granting permission to use the articles here. This research was supported (in part) by a Summer Stipend from the Research Center for the Humanities and Social Sciences at William Paterson University. I thank the Research Center for its support. A section from chapter 5 was presented at the 2013 Shakespeare Association of America Meeting. I thank Evelyn Tribble for organizing the seminar and the other seminar participants for providing helpful feedback.

I owe an especially heartfelt acknowledgment to my wife, Molly McKenney, who tirelessly helped me through the many anxious moments as I completed this book. Finally, I dedicate this book to my parents, Janet and Philip.

Introduction

I was chosen in the eighth grade, despite my vocal opposition, to play the part of Richard III in a school production of Shakespeares play. As an especially brooding teenager, my English teacher apparently felt that I would be perfect for the part of Shakespeares malcontent king. While my teacher undoubtedly believed it was a great honor to play the title role in a Shakespeare production, I certainly failed to see it that way. Growing up in a blue-collar household, I had the distinct understanding that Shakespeare was not for me. In my hometown, an affluent Boston suburb, Shakespeare, the ultimate symbol of social distinction, was better suited to my more culturally literate and economically advantaged peers, the children of doctors, lawyers, and university professors. High culture was something others enjoyed, a privilege that was off limits to regular people who lacked the resources to attend more refined cultural institutions such as the theater. In this instance, however, I had no real choice in the matter, and so I soon found myself in the school auditorium, nervously waiting for the curtain to rise. As I adjusted my withered arm for maximum effect and arched my shoulder until it resembled a hump, I watched my classmates, adorned in elaborate homemade costumes, pose for their proud parents. My own costume was little more than a black bed sheet, worn as an ill-fitting cloak, which my teacher and some of the other parents had tried to improve at the last minute before the show began. Strangely, I remember very little of the actual performance. Instead, I remember mostly a feeling of profound inadequacy as I stood on the stage. I was a working-class stereotype: an academically unremarkable son of an Irish American firefighter and a waitress. And here I was performing Shakespeare before a mostly upper-middle-class audience, awkwardly filtering blank verse through a thick New England accent while wrapped in an old bedsheet and balancing a Burger King crown atop my head.

At the time, of course, the experience was rather traumatizing, and it only served to reinforce my sense of alienation from Shakespeare. As the years passed, however, and as I rediscovered Shakespeare as an undergrad, I began to reevaluate the plays. If initially Shakespeare had been a marker of class difference, I now began to see my own class background reflected in the plays. I fell in love with Shakespeare in college, not because I acquired a newfound taste for high culture but, on the contrary, because Shakespeares plays affirmed my own low-culture, working-class ways of seeing the world. The trials and tribulations of kings and aristocratic lovers were moving, but equally gripping were the struggles of marginalized characters like Caliban, Ariel, Dogberry, Touchstone, and Bottom. These laborers of various sorts, it seemed to me, faced the same kinds of social indignities and inequalities that I had always associated with Shakespeareor at least with those who claimed Shakespeare as a marker of class and cultural distinction.

My new appreciation for Shakespeare developed more critical scholarly dimensions as I became increasingly aware of the dearth of academic attention to questions of labor and class in Shakespeares plays. Sharon ODair, in a similar consideration of Shakespeare and class, suggests that this critical blind spot is structural to the university as an institution: in the academy as we know it, the affirmation of a lower-class identity is hardly compatible with an (upper) middle-class identity, which is what higher education affirms. Working-class kids who succeed in the academy or subsequently in the professions are reconstituted and normalized as (upper) middle-class. In the academy, working-class identity is not merely not affirmed, but actively erased. To read the drama of Shakespeare and his contemporaries against the grain of much contemporary criticism is ultimately to situate early modern drama in relation to an emerging working-class formation in the period. And because this class identity is actively erased within the university, reading early modern drama with an eye toward laborers requires an open-mindedness to counterintuitive understandings of the plays.

Next page

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.