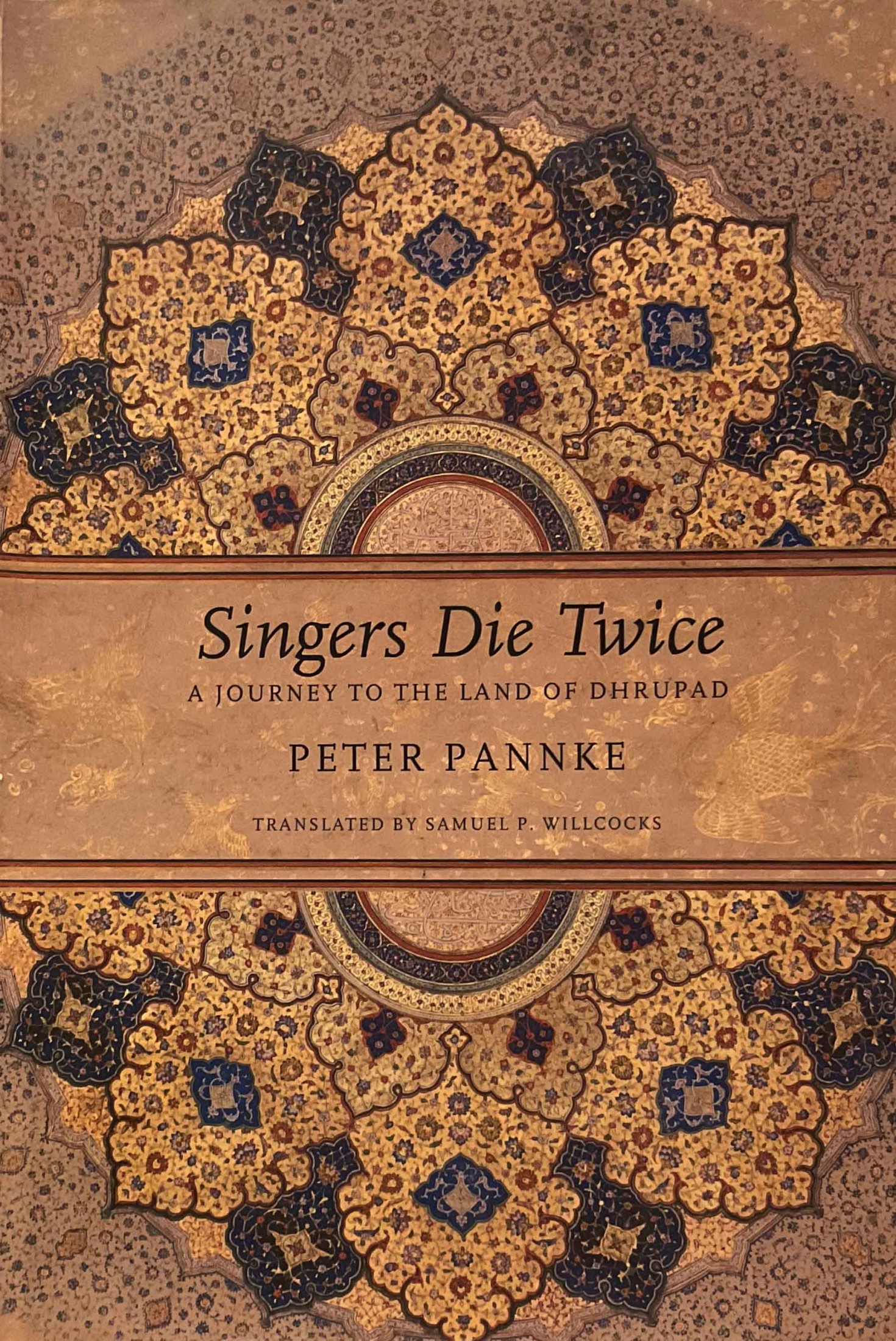

PETER PANNKE

SINGERS DIE TWICE

A Journey to the Land of Dhrupad

Seagull Books, 2013Originally published as Sanger Mussen Zweima l Sterben by Peter PannkePiper Verlag GmbH, Munich, 2006English Translation Samuel P. Willcocks, 2013 ISBN 978 0 8574 2 104 3British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

Before anything else, India is a smell. Lightning fast, it finds its way deep into the brain. Next, you hear sounds, then images start to flicker. Sight comes later, thought last of all. The brain takes in the outside world through the nostrils, the retina, the eardrums, the skin, until everything is turned into memory.

Every time I arrive I experience India piercing its way into me, unfolding in a trice. The first breath is the biggest shock; later, when Ive picked up the scent of this great animal, I cant smell it any longer. Hardly have I left the country than it fades away, nothing but a vague shadow, beyond the grasp of nose or brain.

I try to remember.

I

Indira Gandhi International Airport, New Delhi, Monday, 29 July 2002

It was just before midnight but the road downtown from the airport was still busy. When I had arrived the previous winter, the city lay like a lazy lizard, the blood in its veins cold, almost at a standstill, only now and then shifting sluggishly and stretching its legs. This time, there were no fires burning at the roadside where those out at night could warm their hands. Everyone was awake, out and about, up and at it. The people outside the taxi window were seizing the chance to breathe freely in the shadows, in the night, before the next day dropped on them like a stone from heaven, heavy, hot.

July was almost over but not a drop of rain had fallen yet. Delhi was smothered by a pall of dust and groaned like a woman spurned by her lover. Her desire had mounted ever higher as she waited for the monsoon, burning with her need, and now she blazed yet more fiercely in disappointment that it had not come. The air shimmered, yellow as sulphur, with a dirty gunmetal taint. During the day it sucked up tonnes of lead from the car exhausts, which rained down at night as sour soot all across the city. Drifting mist melted before the light from the headlamps as we approached the city.

New Delhi, 1978

Years ago in India, I dreamt of my death.

Im standing in a long queue of people, all of them waiting for Death, who has taken the shape of a black-clad woman. She embraces everyone waiting in line and slips a slim blade into their back. Behind me, I see a group in turbans and long white robes, who are in a fearful hurry. Every so often, some of them run as fast as they can past the rest of the queue, to the left and the right, shoving others aside, and hurl themselves eagerly into the black-clad ladys arms. I cant see her face; she wears a black mask with a pattern of silver lines incised.

When its my turn, she embraces me. I note how the blade strikes me between the shoulder blades. Its only a tiny sting but I feel it sharply. Then she turns me upside down, sets me on my head and embraces me a second time. This time, the sting strikes me in the lower spine, at the sacrum.

I look at her questioningly. Singers have to be stabbed from both ends, she says. Singers must die twice.

New Delhi, Monday, 29 July 2002

When my friend Premkumar called from Allahabad, I was in Berlin. His father, singer Vidur Mallik, whom I had known for almost thirty years, had died and had been burnt the same evening as tradition demanded. He had been cremated at Triveni, the confluence of the Ganga, the Yamuna and the mythical Saraswati. The family was beginning to gather for the last rites in his home village in Bihar.

Amta, the village of the Malliks, is near the former royal capital at Darbhanga. The maharaja had granted it to the forefathers, who founded the family line, as a reward for bringing the rains with their song. That was in 1785; East India Company annals record the worst famine of the eighteenth century in those years. It hadnt rained for three years and the land was parched. The two founding fathers, Radhakrishna and Kartaram, had sung up a storm with their magical rain raga, a storm so intense that the land was flooded. Premkumar Mallik had told me the story over and over again, lifting his hand to his chest to show how high the water had risen.

The puja that must be performed after the death of a patriarch from the Gaur brahmin caste, as Vidur Mallik had been, is long and laborious. It dates back to the beginning of creation. The ancestors are invoked, gods and demons are invited to the ritual feast. A hundred and twenty-five thousand yonis must be fed, the cosmic vaginas that gave birth to all life, to insects, animals, birds and every other creature, including the pretas and the bhutas, the hungry demons. The manushya, the human race, were born last. Villagers from all round are invited to the feast that would conclude the puja.

Although I had booked the next flight to Delhi, it would still take me several days to reach the remote spot. The puja had to be performed within thirteen days and I hoped to be there for the final rites at least.

Old Delhi Railway Station, Tuesday, 30 July 2002

On the way to the railway station, the images at the side of the road flickered in the hot air rising from the asphalt. Heat lay over the houses in a venomous yellow haze. Vultures wheeled above downtown. Rickshaws, taxis and buses crawled agonizingly through the furnace air. The drive took us across the broad square that spreads out between the Jama Masjid and the Lai Qila. Pedestrians trotted across the open space, drenched in sweat, trying to reach the shade of the next tree as quickly as they could.

The Old Delhi Railway Station is the less busy of the citys two large stations. The New Delhi station is for passengers to the metropolises of Bombay or Calcutta, while the Old Delhi station offers connections to the wide plains that stretch away northward as far as the Himalayas. Darbhanga is in the northeast. Only a few years ago, the journey would have taken several days, changing several times from train to bus to rickshaw, but now there was a direct connection, a train called the Sha-heed Express, the Martyr Express.

Its a train from one no-mans-land to another. It sets out in the west from Amritsar, the last Indian city before the border with Pakistan. It was in Amritsar that Indira Gandhi had ordered the storming of the Golden Temple in 1984 when her protege, the rebel leader Sant Bhin-dranwale, broke loose and declared an independent Sikh state. The Amritsar temple precinct became the last refuge for his armed followers. There was never any official death count but the rusty red bloodstains left behind on the marble tiles are still shown off like stigmata. When the prime minister was shot by her bodyguardsalso Sikhsshortly after Operation Blue Star, thousands of Sikhs were massacred on the streets of Delhi, car tyres hung round their necks, set alight with kerosene. It was two days before the army intervened. The bodyguards were hanged in their turn. Martyrs wherever you turn. Shaheed Expressthe name sounded rather ominous for my journey.

Indian trains are generally overcrowded but there was no such trouble with the Shaheed Express. Clearly Darbhanga didnt draw in visitors, but there was another reason the compartments were so empty the east of India was largely under water and no one knew whether the train would reach its destination. In the west, by contrast, not a drop of rain had fallen and not even the meteorologists could say whether this year the monsoon might not miss Delhi entirely. It was notoriously unreliable and had grown even worse since the late eighties; there had been several catastrophic droughts and floods since then. It was already apparent that this year would be worse than the year before.

Next page