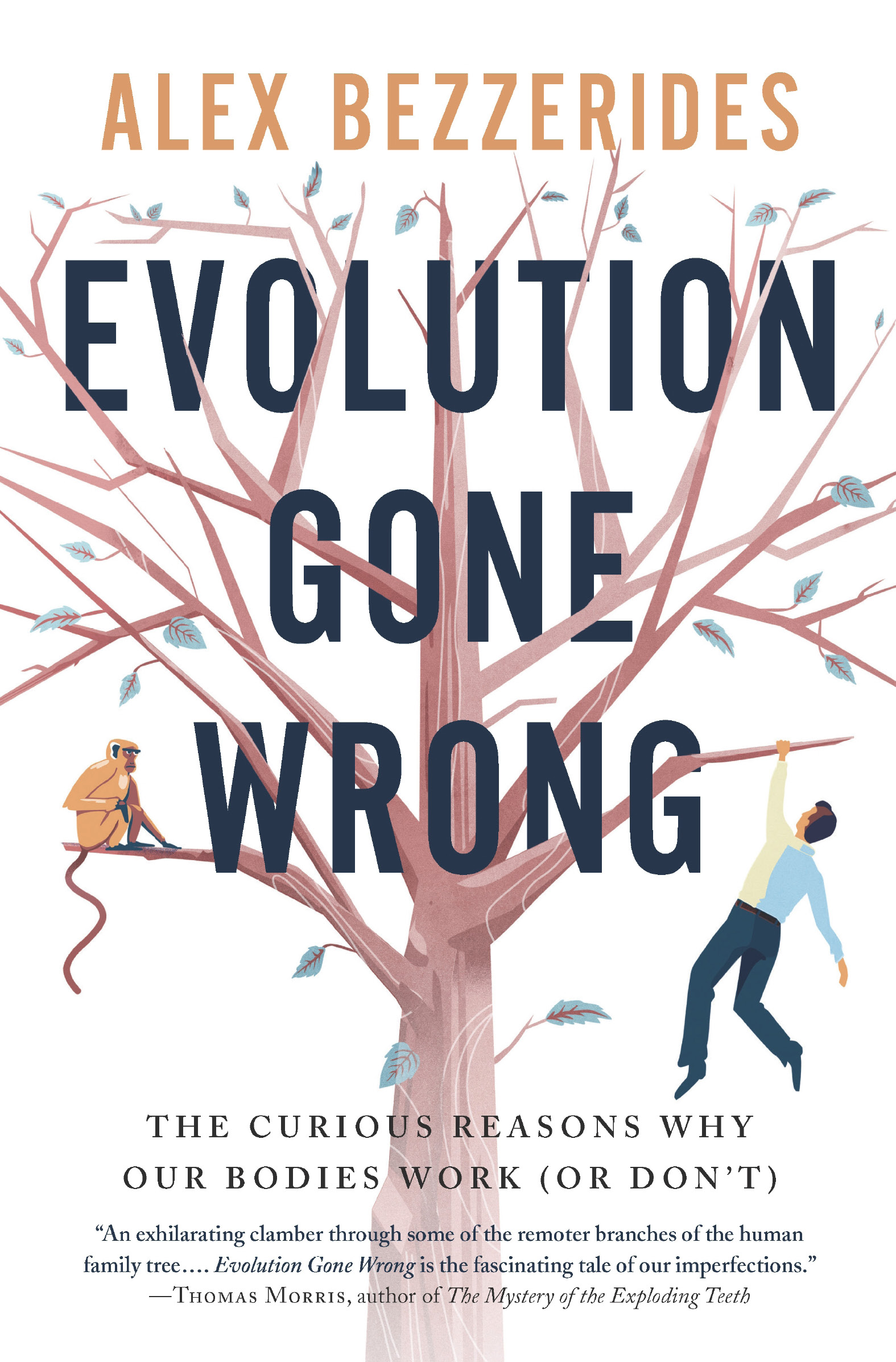

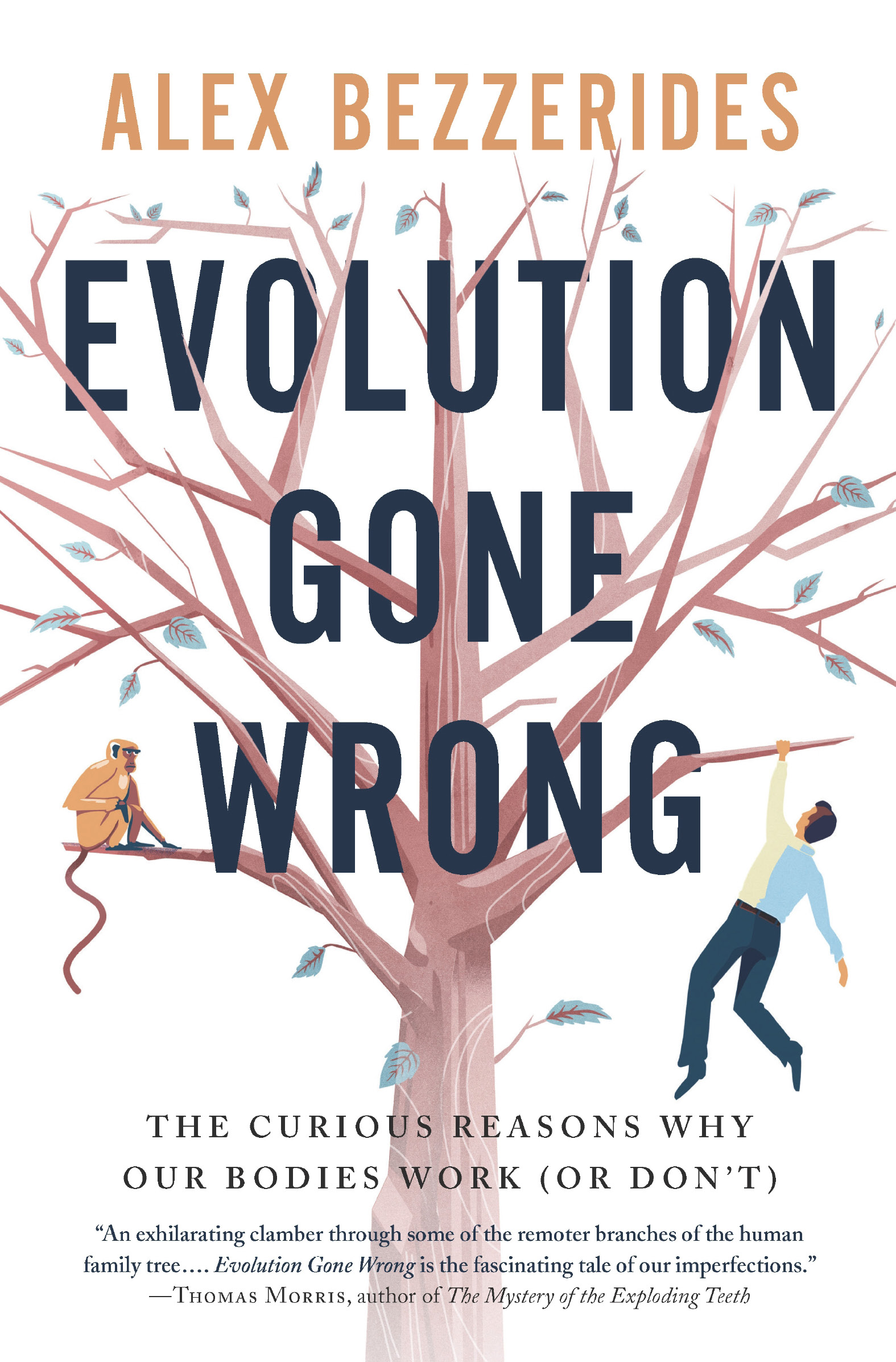

Alex Bezzerides

with illustrations by Peter Davidson

Evolution Gone Wrong

The curious reasons why our bodies work (or dont)

For Julie and Ellie

Contents

Introduction

Its Not Your Fault

Which animal climbs down from its tree once a week to do its business?

a. koala bear

b. three-toed sloth

c. common ringtail possum

d. spider monkey

I would be willing to bet at least one of these statements is true about you: you had your wisdom teeth pulled, you wear glasses or contacts, you snore, you have sore feet, you have back pain. If you are unlucky, all of those statements might be true. You have probably spent considerable time and money in an effort to alleviate the pain and discomfort from such ailments. From dental work to prescription lenses, pharmaceuticals to customized mattresses, humans spend a lifetime trying to relieve symptoms caused by their anatomical imperfections. But have you ever stopped to consider why those aches and pains occur in the first place? Why dont our teeth fit in our mouths? Why do so many people have blurry vision? Why are our knees and ankles always getting sprained and twisted? Why are our backs so delicate we have to worry every time we bend over to pick something up? It is not just the aged who suffer from these maladies. Seemingly from birth, humans are uniquely prone to bodily discomfort and malfunction.

This book is about the aches and pains of the masses and why they happen. It is not about obscure conditions you only ever hear about from some aunt you see during the holidays. It is about your body and why it often does not work as well as you might hope or expect.

Dont worry, the book is not a long, drawn-out guilt trip; the focus is not on all the problems humans bring upon themselves with their unhealthy behaviors. Thus, topics like atherosclerosis, lung disease, and cavities are off the table. I am not going to give you a hard time about your diet, how much you exercise, or how infrequently you floss. Instead, this book will provide explanations for anatomical imperfections that are not your fault, like having crooked teeth or flat feet or waking up with a sore lower back. But why do those issues happen? What happened along the long, complicated arc of human evolution to leave us with bodies that fail us in such predictable ways?

Biological Mash-up

The causes of our bodily shortcomings are rooted in both evolution and anatomy. I am uniquely qualified to cross over between those two disciplines, kind of like Taylor Swift moving between country and pop. My country music years were my graduate training in evolution and ecology. When not doing research and writing journal articles, I was teaching, and I learned that I preferred being in front of a class to being behind a lab bench. So after finishing graduate school, I applied for teaching-heavy appointments rather than jobs with more of a research focus.

My first academic job was at a small college in northern Wisconsin, where they needed me to teach human anatomy and physiology (A&P). Like Taylor Swift switching to pop, I pivoted and shifted my focus as a biologist from asking questions about natural selection and population ecology to learning the best ways to teach students about digestion, respiration, and the endocrine system. Unlike Taylor Swift, my starting salary was $41,000, which was somewhat humbling having recently finished a decade of undergraduate and graduate studies. It turns out theyre right when they say you dont get into teaching for the money.

I eventually ended up at a small college in the western United States. I still teach a significant amount of A&P, but working at a small campus allows me to throw a broad disciplinary net. Over the years Ive taught classes that run the gamut from entomology to human dissection. When people ask what type of biologist I am, I never know quite what to say. I am a biologist who can identify beetles, but I can also tell you how your kidneys work. I am not sure what type of biologist that makes me. I think it just makes me a biologist, period.

My Pain Is Your Pain

I was not inspired to write this book by some set of unbelievable circumstances. I never lost half of my large intestine in a grizzly bear attack. I did not nearly die from Dengue fever while attempting the first descent down an unexplored river in Africa. I do not suffer from any unusual genetic conditions, autoimmune disorders, or physiological anomalies. I have a normal, middle-aged body, which means I have the same types of problems everyone has. My teeth did not come in particularly straight. I blew out a knee playing basketball. Sometimes my back gets sore enough that it is hard for me to sleep.

I did not think much about these ailments for years because none of them caused me an inordinate amount of trouble. I was also busy learning and teaching about all the ways the body works when it functions normally. Human anatomy and physiology is a complicated subject, and it takes a long time to get a handle on how the body runs under typical, pain-free circumstances. There are several good A&P textbooks, and all of them are more than 1,000 pages long. In the early years of my career, I was not thinking about the origins of conditions like myopia or bunions or gestational diabetes. I was more concerned with distilling those 1,000-plus pages into two semesters of course content in order to teach scores of future nurses and doctors how eyes, feet, and uteruses typically work. Questions about issues like choking, torn menisci, and the pain of childbirth came to me later after I had established a foundation of knowledge about how our bodies work.

How Questions

Biologists, and their students, learn about bodily systems by asking questions. They can ask proximate questions in which they try to understand how something works. They can also ask ultimate questions where they try to answer why a structure, process, or behavior is the way it is. Proximate questions take up most of the time in an A&P class. How do heart valves control blood flow? How does the ACL restrict the movement of the knee? How does the cornea refract light? Most of what we know about human anatomy and physiology comes from answers to those types of how questions. It makes sense because if you need to repair a heart valve, put a knee back together, or use a laser to correct someones vision, you need to know how the structures work in order to fix them.

How questions can have tremendously complicated answers. Teaching and learning A&P often does not extend beyond the proximate level because it takes so long to understand proximate-level questions and answers. For example, to teach just the basics of muscle contraction it takes several drawings, considerable discussion, and more than an hour of class time to cover physiology that, in real time, occurs in a fraction of a second. And, mind you, this happens in a lower-level undergraduate class. If students revisit the subject in graduate or medical school, they learn many more layers of detail.

Why Questions

Even while spending so much time on proximate mechanisms in A&P, I never completely broke the habit of asking ultimate questions because of the other classes I teach. Ultimate questions get at the evolutionary roots of a topic. For example, in my class on animal behavior, instead of teaching how dolphins jump out of the water (which involves much of the same minutiae about nerve conduction and muscle contraction covered in A&P), I ask my students to think about

Next page