Table of Contents

Also by Mary Cappello

Night Bloom

Awkward: A Detour

Called Back: My Reply to Cancer, My Return to Life

For Jeannie and Jim,

for Malaga, and for Russell.

I gulp. You gulp.

We are always at, or on, the oral stage wherever else we are.

ADAM PHILLIPS, The Beast in the Nursery

AUTHORS NOTE

I use the following abbreviations throughout this book to refer to texts by Chevalier Jackson that I rely on most frequently: LCJ for The Life of Chevalier Jackson: An Autobiography; DAFP for Diseases of the Air and Food Passages of Foreign-Body Origin; NMP for New Mechanical Problems in the Bronchoscopic Extraction of Foreign Bodies from the Lungs and Esophagus; B&E for Bronchoscopy and Esophagoscopy: A Manual of Peroral Endoscopy and Laryngeal Surgery. I rely throughout on Jacksons abbreviated coinage fbdy to refer to foreign body. I capitalize the word thing when I want it to refer to an object that has undergone a transformation once it has been swallowed, retrieved, studied, and placed in Jacksons collection, or for objects that, by way of over-valuation, exert an auratic charge.

I.

WHOWASTHAT MAN?

What was so potent about these protected objects? Was it that my world was kept out? Or that some imaginary world was kept in?... It took very little time to see that the objects spoke to one another, and to me.

ALLEN KURZWEIL, The Case of Curiosities

Alone on Floor with Pile of Buttons

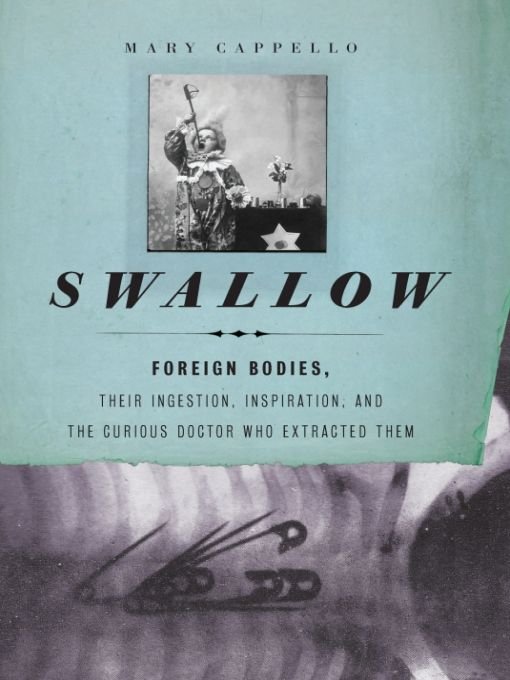

This is a book about stowage and retrieval.

A book made of things found in a cabinetnot just any cabinet, but a recess containing a plenitude beyond all human measure. Not just any things, but wondrous, weird, and even sacred things. Many things that had one thing in common: a strangeness that conjoined them without making them into twins. Common objects turned into mysterious markers because of what theyd been through, where theyd gotten lost, and how they were later found. Here are capital Things, and so I will capitalize them. Here are trinkets not reducible to trifles.

The regularity of living (or its pretense) seems at odds with the fabulous specimens in Philadelphias Mtter Museum, a repository of medical curiosities created to instruct nineteenth-century practitioners. The building is unprepossessingit could be an elementary school with its Aladdin lamp insignia and shoe-buckle window designs, offset by its stately marble floors; the edifice is small, not grand, made intimate by its adjacent medicinal garden and cherrywood doors. But does anyone who enters its hallways afterward forget what he has seen? In 1858, Thomas Dent Mtter, a prominent Philadelphia surgeon who specialized in treating cases of clubfoot and harelip, endowed the museum and contributed his collection of seventeen hundred anatomic and pathological specimens and other assorted items to the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. One of the oldest private medical societies in the country, the college included Benjamin Rush among its founders; it was at Rushs suggestion that the garden was created to stock doctors individual medicine chests and to inform a pharmacopoeia-in-the-making.

Whats the distance between a face caught in a cornice on an apartment building across the way and the human skulls arranged on shelves inside the Mtter Museums glass cabinets? Across the street from the museum on Twenty-second Street, theres a facade made of bodiless singing baby heads stuck inside bonnets made from their cut-off armsor are they the wings of angels into which their heads are nestled, out from which their open mouths protrude? I think they are diminutive gargoyles, hark-the-herald pudge-ims who have forgotten their origins as gargoyles, hewn from gargouille (Old French) and gurgulio (Old Latin), words that refer to the throat, or to the gurgling sound of water a gargoyle displaces through the spout that is its mouth.

Its impossible to escape a sense of the uncanny herethe sudden recognition of what was once believed, later strenuously forgotten, and now again confirmed, and I wonder how many are tempted to follow a particular item in the museum to an end and a beginning and back again. Toward multiple beginnings, and multiple ends. Even those who havent been to the Mtter Museum may have heard of its horned woman replica, its displays of Siamese twins, its wall of eyes, or its numerous anatomical figures in wax that so closely approximate human flesh they animate that all-too-narrow threshold between the living and the dead. On the ground floor of the museum, as I round a bend past the skeleton of a giant, my eyes widen to take in, in adjacent glass cases, an enormous bowel, better suited to a dinosaur than a man but nevertheless extracted from a diseased human body, and the tiny, handsomely articulated bones of a fetal skeleton arranged in perfect rows of white against black. Between the bowel in its waterless aquarium and the baby bones inlaid into velvet like a set of numbered jewels sits an unremarkable oaken girth, a solid piece of furniture that you might have to be bookish to notice at all. In fact, in my fascinated stupor, I had missed it; I was busy examining an ill-lit collection nearby that seemed to contain a cross between seashells and miniature musical instruments but that was actually a gathering of cartilaginous labyrinths and cochleas, the significant bits of bone that govern balance, when my friend called to me: Get a load of this! Take a look at this!

The case, at the time of this writing, is awkwardly situated beneath a staircase, so if you stand to one side of it, you can hear the patter of other visitors on the stairs; in order properly to view it, you might have to bend so as not to hit your head on the stairways metal underside. Resembling an old waist-high library card catalog, the cabinet is heavy and windowless but features rows of handles waiting to be pulled. The Mtter Museum isnt, like Philadelphias childrens museum, a Please Touch museum, so one might feel wary of the invitation offered by a placard to OPEN the drawers.

Might the slender crypts be filled with slabs or parts of bodies? The crude and unpliable instruments of early medical practice? The scarily heavy shackles used in the eighteenth century to subdue the mad? The jaw tumor of Grover Cleveland? Human placenta? No. These items are all on plain view in other corners of the museums small rooms and alcoves, whose wooden cabinets loom in chorus as if to echo the seriated arches of the Unitarian church next door. Could the cabinet be the apothecary accompaniment to the medicinal garden? A pullout drawer whirs on its ball-bearing casings to reveal a carefully arrayed collection of small objects mounted inside little squares, numbered, secured in place with a thread or a wire, and framed. But what order of things are these, and who could have been responsible for their steadfast arrangement? What form of wondrous derangement have we here?

The objects in this set of drawers are items that have come into unnatural contact with the human body: not butterflies, moths, or beetles, these are indigestible and undigested things, Things that people have swallowed or inhaled. A pioneering laryngologist named Chevalier Jackson and the colleagues whom he trained extracted nonsurgically more than two thousand foreign bodies from peoples airways and stomachs and then preserved them in this cabinet, and in this way gave back to them a local habitation and a name. (See .)