Tiger: The Life of Tipu Sultan

Preface

Timeline

c. 1720: Haidar Ali born

1750: Tipu Sultan born, 20 November

175152: Siege of Tiruchirappalli

1761: Haidar secures total power in Mysore

1767: Outbreak of First Anglo-Mysore War; Tipu receives first military command

1769: First Anglo-Mysore War ends

1774: Tipu marries first two wives

1780: Outbreak of Second Anglo-Mysore War; Battle of Pollilur

1782: Death of Haidar: Tipu assumes power

1784: End of Second Anglo-Mysore War

1785: Kodagu rebellion crushed

1786: Embassy to Ottoman Sultan sails from Malabar coast; Earl Cornwallis appointed British governor-general of India; Marathas invade northern Mysore

1787: Tipu concludes peace with Marathas; Embassy to French king departs

1788: Kodagu rebels: regains most of its territory

1789: Embassy to French king arrives home

1790: Embassy to Ottoman Sultan arrives home; Outbreak of Third Anglo-Mysore War

1792: End of Third Anglo-Mysore War: princes taken hostage

1794: Princes return to Mysore

1797: Lord Mornington appointed British governor-general of India

1798: Tipus embassy reaches Mauritius; French governor issues proclamation; Proclamation published in Calcutta newspaper

1799: British and allies invade Mysore: Tipu killed 4 May

Myth vs Reality

Windsor Castle, a popular tourist destination not far from London, is an ancient seat of the British royal family. On days when the grand galleries, with their splendid royal portraits and luxurious furnishings, are open to the public, the visitor can view a number of cabinets displaying items from the Queens collection, many acquired as gifts from loyal subjects to whichever sovereign sat upon the throne. Naturally, for a monarch, only the most magnificent of objects would do. Around two hundred years ago, a number of Indian artefacts came into the collection, presented to George III and his successors. They were war loot, seized after the fall of Srirangapattana, the capital of Mysore, in 1799; all had belonged to Tipu Sultan, the late ruler of that kingdom.

The most stunning of the objects in the cabinets is the life-sized gold tigers head that formed part of Tipus throne, known colloquially as the Massy Tiger. Crystal teeth bared, it glares through the glass as if permanently outraged by its owners inglorious end. Nearby is one of Tipus war banners; made of green velvet, it is decorated with a stylised calligraphic tiger mask. Deciphered, the calligraphy reads asad allah ul-ghalib , the victorious lion of God. Among other items of loot gifted to the British king were a jewel-encrusted huma bird that had stood atop the canopy of the throne, a war dress and helmet, a cotton tent panel patterned with tiger stripes, some velvet palanquin cushions, again with tiger stripes and embroidered in silk and gold, and one of Tipus seals. But this was only a tiny fraction of the vast amount of plunder seized by the victorious troops in the aftermath of Tipus death. So extensive was the looting, numerous artefacts associated with him can be found scattered across the British Isles in museums and other collections. From the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh to Powis Castle in Wales to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, todays tourist can see displays of Tipu memorabilia from the martial to the mundane.

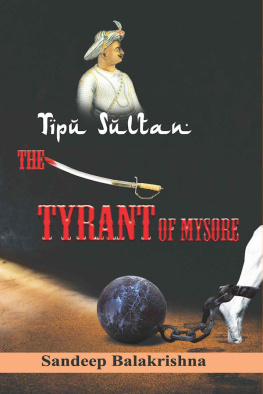

For thirty years, first Haidar Ali, Tipus father, then Tipu himself, had been at the forefront of the British publics consciousness. Terrifying tales of attacks on British forces and threats to trading settlements such as Madras appeared in the newspapers of the day, embellished by distance as they were carried home by sea. Over the decades and through four Anglo-Mysore wars, people hungrily awaited reports of the latest outrage perpetrated by the so-called tyrants. The return of British prisoners of war, some of whom had been held captive in Mysore for several years, led to the writing of books that told harrowing stories of hardship and torture. That many of these accounts were self-serving was of little interest to their avid readers. So by the time he died at the hands of General Harriss troops, as they besieged his island capital in 1799, Tipu Sultan was possibly the most famous Indian, if not villain, in the United Kingdom.

Not surprisingly, celebrations in Britain at the news of Tipus demise fuelled further creative output on the part of not only authors and playwrights but also artists, who put paint to canvas to glorify the victory. Careers were launched and some ended. Arthur Wellesley, later to become the Duke of Wellington, famous for defeating Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo, was placed in charge of Srirangapattana and then went on to overcome the Marathas in 1803, at the Battle of Assaye. India was Wellesleys proving ground. The governor-general, Lord Mornington, who was Arthurs older brother Richard, did not fare so well. Having ordered the attack on Mysore in defiance of his political masters at home, and despite energetic attempts by his supporters to vindicate him, his only reward was an undistinguished Irish peerage and retirement. Well into the nineteenth century, the infamous figure of Tipu Sultan held sway in the public mind. As late as 1868, Wilkie Collins chose the siege of Srirangapattana and its subsequent looting as the setting for the opening of his bestselling novel The Moonstone .

One has to wonder what Tipu would have made of it all. Also, would he have cared? Very probably, he would. To terrorise his enemies was his goal and in that he had succeeded, not only through his actions but also by his clever use of imagery and symbolism. Although he did not realise it, his choice of the tiger motif for his insignia resonated strongly with the British, whose own emblem is the lion. It is no coincidence that the Seringapatam medal, awarded to those who had taken part in the siege, depicts a rampaging lion mauling a supine tiger. The ecstatic celebrations would also have confirmed in Tipus mind that he had been correct in his assumption that the East India Companys expansionist activities were a credible threat to the freedom of the subcontinents inhabitants, that he was the last bulwark against British imperial desires. It is this prescience that distinguishes Tipu and his father from their contemporaries. With Tipu gone, the Company was able, in his own words, to fix [its] talons ever deeper into Indian soil.

Local rulers and chiefs, such as the Nizam of Hyderabad or the Maratha Peshwa, frequently failed to recognise the danger posed by allowing British Residents ostensibly ambassadors but in truth much more than that to be assigned to their courts. In contrast, Europeans were forbidden from entering Mysore territory uninvited, for whatever purpose, on threat of imprisonment. Those who did make the mistake of crossing the boundaries of the realm soon found themselves in difficulties, sometimes forced into military employment even if they were completely untrained. When one man who ended up in this position an English clerk who had unwittingly wandered across Mysores border protested that he had no skill in warfare, Haidar responded that he never doubted the soldiership of a man who wore a Hatt, and proceeded to recruit him. The Mysore ruler and his son understood all too well that what set European armies apart from Indian troops was their technical expertise and superior discipline, and they set about correcting the imbalance through the use of French mercenaries.

Haidar and Tipus closely guarded borders meant that their adversaries were forced to rely on second-hand reports, usually from spies. One of the tasks of the Companys Residents at Indian courts, such as Hyderabad or Pune, was the recruitment and management of secret agents. They also monitored reports the Indian rulers received from their own informants. As is always the case with espionage, the risk of betrayal and double-cross was ever-present, as well as unfounded rumour. In such an environment, of subterfuge and incomplete information, threats can be magnified, feeding the existing paranoia about the enemys intentions. By the time Lord Mornington made the decision to order the invasion of Mysore in February 1799, any semblance of reality concerning the threat Tipu posed had long been lost from sight.