To the memory of Pedro Boadas Rivas, direct-action anarchist.

Circumstances of My Relation with Some of the Protagonists

In 1946, I was twenty-two years old and imprisoned at Miguelete Jail for some serious acts of bloodshed that had taken place in Mercedes, my hometown. It was under these circumstances that I met Pedro Boadas RivasCatalan, anarchist, and one of the participants of the robbery of Cambio Messina currency exchange. He had been temporarily transferred from Penitentiary.).

Although I must admit that, for me, some of the values of that barbaric culture still hold true entirely, the truth is that when I met Boadas Rivas and the other direct-action anarchists, my ideological universe was poor and limited; those things I was interested in were simplistic and few.

A couple of days or weeks after my meeting with Boadas Rivas, I became fully identified with anarchist doctrine. My very first libertarian readings happened during my time in Miguelete Jail, but they werent many, for Boadas Rivas did not have much reading material available.

The following year, 1947, I requested a transfer to Penitentiarysomething that was unrelated to my friendship with Boadas Rivasand it was granted to me promptly. At the time, in order to avoid the overpopulation of prisoners in Miguelete, correctional authorities used to transfer small contingents of prisoners (whose legal condition was that of defendants or indicted) to Penitentiary, where there was a special wing destined exclusively to defendants, which was completely separate from the one reserved for the condemnedcertainly the vast majority of the prison population. The prisoner population of the defendants wing was about one hundred inmates (the condemned were about four hundred, if I remember correctly). Thats where I met the rest of the direct-action anarchists. On average, they were men of about fifty years of age; a human generation lay between them and I, and they had been imprisoned since the 19271933 period. Due to an old flaw in the Uruguayan penal system, all of them spent most of their time as defendants. In the early 1950s, they became condemned and wore the respective uniform. A little later, between 1951 and 1953, they were released. Their time of incarceration lasted an average of twenty-two years.

For my part, I spent seven years in Miguelete Jail and Penitentiary (and one year and several months in Mercedes jail prior to that), regaining my freedom in April 1952. During that time, I spent six years behind bars with the direct-action anarchists, including a few months when I was the cellmate of Domingo Aquino and Jos Gonzlez Mintrossi, whom we will speak of further on.

When I got my transfer to Penitentiary in April 1947, my relation with Boadas Rivas and his ideological universe was a year old, and though he had remained behind in Miguelete (if I recall the dates correctly), my contact with the anarchists in Penitentiary was instant. There, I met Vicente Moretti, Domingo Aquino, Jos Gonzlez Mintrossi (El Chileno or the Chilean), Virginio Toms Denis, and Rudecindo Rodolfo Musso (released a short time after I arrived).

Later on, in 1949, I met Gabino Ortells, who had been brought from Miguelete Jail.

As we shall see when we address the story of their past actions, the little group of direct-action anarchists in Penitentiary in 1947 could be divided into three subgroups if we consider the events in which they had participated: a) Cambio Messina: Pedro Boadas Rivas and Vicente Salvador Moretti; b) Shootout in Paso Molino: Gabino Ortells and Virginio Toms Denis; c) Attacks against Pesce and Pardeiro, Lecaldare case: Domingo Aquino, Jos Gonzlez Mintrossi (El Chileno), and Rudecindo Rodolfo Musso.

The rest of the participants in the fifteen cases that make up our investigation into the direct-action anarchists in Montevideo between 1927 and 1937 had already been released by 1947, were on the run, had died, or had disappeared. One of them (Bonaparte) was incarcerated in Vilardeb Hospital.

In this chapter, we will deal only with the seven individuals mentioned above, who I knew personally. Let us begin with Pedro Boadas Rivas. He was a tireless talker; his topics were the critique of society in general; the anarchist militancy in Barcelona during the 1920s; different episodes of his long time behind bars; football (he was a Barcelona fan); gambling ( quiniela ). In regard to the latter (played clandestinely in Penitentiary), Boadas Rivas had a sort of lucky charm or formula to always win, which entailed intricate arithmetic operations on long sheets of paper. His character was open, rather joyful. His health, strong, through and through. His vice was smoking, quite over the top. Like everyone else in the prison world, he rolled his own cigars, but in his case, such was the urgency that he hadnt even finished smoking one that he was rolling the next. He was careless in his attire and, apparently, in his cell hygiene. A prison superintendent visited his cell once and said to him, Boadas, I dont like this cell at all, to which the Catalan replied, Me neither. Nothing happened, of course. That superintendent, who didnt seem to hate anarchists much, left without pressing further.

Boadas Rivas corresponded, albeit very few and far between, with two female cousins who lived in Barcelona. He spoke with earnest affection of those cousins, and he once had his photo taken and sent it to them. I dont recall, however, that his former companion ever wrote to him, though its possible she did so without Boadas mentioning it. A little after his release in 1952, Boadas Rivas managed to bring his old companion from Europe; his eldest daughter, Carmen; and his grandson. Im not aware of the details, but he probably did it, at least in part, with his earnings as a newspaper seller in Cerro. It was during that time that I met Boadas Rivass family. His former wife suffered an illness that obliged her to use a wheelchair to move around, but one could see that Boadas was happy in her presence. (Perhaps true love does not need to be requited.)

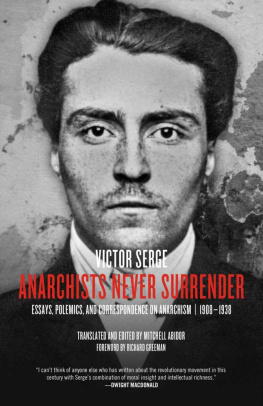

Between 1952 and 1972, I met Boadas Rivas several times in Cerro, where he lived and worked as a newspaper seller. I once asked him to hide a gun for me; he agreed but warned me he wouldnt have it in his home. (Boadas Rivas was solidary but didnt chew glass.) Another time, I said that I wished to write about his life, and he replied that he didnt mind answering any queries to satisfy my knowledge, but with the condition of not publishing anything. Nevertheless, he agreed to an interview about the same subject a little later. (This is not the same article that appeared in Marcha in September 1971.) He died in exile in 1972, when I left for Chile.

Vicente Salvador Moretti was a man of short height; he suffered from a stomach ulcer; his temper was a little irascible and tough (perhaps his ulcer had something to do with this); he used to say his father had been mateo, a coach master or liveryman, in Buenos Aires. He also loved to talk or be heard (but given that it is so hard to find someone prone to true dialogue, this should not be taken as a criticism). I believe his favorite topic was social critique from an anarchist perspective. During one of those discussions, Vicente ranted against the eliminatory security measures of the Penal Code, which can sentence a person for life in prisontheoretically, at leastand he claimed that a death sentence was, ultimately, much more benign. (Luckily for him and Boadas Rivas, they had been sent to prison before the introduction of this juridical instrument in the Penal Code.) At the time, I mentioned to him that an inmate subjected to such a situation had in the end the chance to kill himself; that is, he had a choice. On the other hand, a death sentence denied this final liberty to him. So I did not share his philosophical appraisal. I dont recall what his reply was, but Vicente surely did not like my sharp retort; he was too sensible to acknowledge the evidence. Moretti had a remarkable ability and the patience to raise birds as difficult to domesticate as a sparrow. He kept one in his cell, which flew freely inside its walls. Needless to say, his owner would never have caged it. During recreation hour, Vicente used to go out into the yard with the sparrow on his shoulder, and once he reached the enclosure, the little bird would flutter about in the huge yard without straying too far, returning every now and then to its owner. He also had two or three canaries in the same condition as the sparrow, with no cage whatsoever. Besides this hobby for birds, Vicente cooked in his cell some delicious puff pastry cakes, which he used to share with me, in compensation for my contribution of eggs and quince cheese. He said that ulcerous men like himself and pre-ulcerous men like I could eat lightly fried puff pastry dishes, like his cakes. I was starting to feel stomach crunches that tormented my sleep at times, and I owe Vicente my very first conceptions of antacids to quell them. In regard to visits, the protagonists of the Messina case received very few, which stretched throughout the years. One of these visitors was Abelardo Pita, an old anarchist militant and secretary of the bakers union, whom I had the chance to meet after my release from prison. (Pita is part of the list of direct-action anarchists, and later on we will find him involved in a serious episode that took place in 1931.)