Prologue

It is strikingly evident that we are witnessing a remarkable renewal of libertarian ideas and practices. The corresponding movements, which have often been taken for dead, demonstrate a surprising capacity for survival that is ultimately sustained by an undeniable fact: we stand before a current of thought and action whose constant presence can be verified since time immemorial. The interest in anarchism is growing at a moment when the word crisis resounds everywhere, along with a growing awareness of the terminal corrosion of capitalism and the general collapse that may accompany it. And it is becoming increasingly obvious that the discourse of capitalthere is no alternative other than our own, they tell usis crumbling. There are ever more people who take notice of this and ask in vain for some explanation about the presumed suitability of that which, given the evidence, no longe r has any.

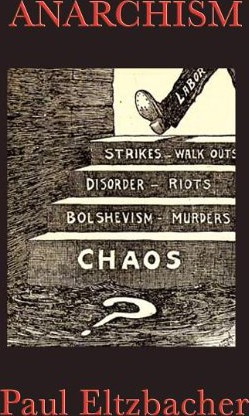

The perception of what constitutes anarchisms virtues and flaws has changed continuously, often notably, over the course of timein particular over the last quarter-century with the collapse of social democracy and Leninism. Many appear to have been mistaken, especially those who saw in anarchism a project completely incapable of addressing the problems of complex societies. The arguments today appear farcical; arguments that continue to be repeated, which suggest that anarchism is a worldview of the past, only imaginablewhatever these terms may meanin the minds of simple people who inhabit backward countries. And it is surprising that there are people who fail to appreciate greater problems with growth, industrialization, centralization, mass consumption, competition, and military discipline. Anarchism does indeed imply restoring many of the characteristic elements of particular communities of the past, but it also involves an effort at a complex understanding of the miseries of the present, venturing in favor of self-management, decommodification, and an awareness of limits.

None of the above should be taken to mean that libertarian thought offers answers to all our concerns, much less that an aggiornamento is unnecessarysomething that at times seems to be indispensable. We are obliged to rethink, or to qualify, many of the concepts that we have inherited from the nineteenth-century classics . We urgently need to adapt anarchist thought to new realities, even more so when the problems it identified a century or a century and a half agoauthoritarianism, oppression, exploitationhave in no way abated. In some sense, we find ourselves before two interrelated paradoxes. The first one reminds us that, while anarchism encounters unquestionably serious difficulties in positioning itself within the societies in which unfortunately it has been our lot to live, there seems to be a growing necessity to confront the calamities of these very societies. The second one underscores the evident weakness of those organizations that claim an anarchist identity, in contrast to a remarkable and more general influence of the libertaria n project.

Therefore it appears ever more pressing to break with the isolation inherent in many identitarian forms of anarchism and to consequently do so from the nondogmatic perspective of those who are necessarily doubtful and who know that they do not holdand I will say this againthe answers to everything. We must face the tension between the inescapable radicalness of the ideas we advocate and the knowledge that these ideas ought to reach out to many human beings and have practical consequences. Unsatisfied with what we are, convinced of our necessity, and conscious of the glories and the miseries of the past, it often becomes clear that we talk a lot, but we do not act in a desirab le manner.

What I refer to above is the mental scenario wherein this book unfolds, which incidentally is a breviary due to its being a compendium of reduced dimensions and not through an imagined pretense that includes some sort of liturgical wisdom. Several years ago, I submitted to print an anthology of libertarian thought that aimed mainly at rescuing texts by the classics , who as far as Im concerned, shed light on many of the challenges we must now face. That is certainly not the aim of this modest volume the reader has in her hands. In no way do I pretend to address in these pages the various debates surrounding such pluralist and complex thought as the anarchist idea. I am content to offer some material open to discussionnever a hermetic and unquestionable textdirected first and foremost to those individuals who possess some kind of militant experience, or a knowledge of it, within social movements or unions, material whose objective is essentially to reflect on what we have done so far, the stigmas we have been cursed withindividualists, hostile to all sort of organization, chiliastics, infantile prepoliticals, et ceteraand what we are supposed to do. So, in case it is not sufficiently evident to the reader, I would like to clarify that this book is in no way an introduction to anarchism that may assess, for instance, the differences between mutualists, collectivists, and communists. It is neither a post-anarchist nor a post-structuralist text, much less a postmodern one, however much it feigns perspectives influenced by a weary zeal upon certainties and established truths as well as an express design to consider at all times the multiple forms of exploitation and alignment that t orment us.

This may be the appropriate moment, then, to warn about a terminological choice that permeates most of this work. Although the adjectives anarchist and libertarian will be taken as synonyms throughout and in such a way that they may be employed without any distinction whatsoever, more often than notas I will explain later onI will reserve the latter to portray positions and movements that are not necessarily anarchist but that nonetheless agree with basic tenets, like those linked to direct democracy, assemblies, or self-management. When I make use of such meaning, the usage of the adjective anarchist will remain circumscribed to the description of positions and movements that assume a clear doctrinal identification with anarchism, understood in its most restric ted sense.

During the task of writing of this work, I have consulted some of the material I have been publishing over the last few years, which has been heavily edited for the current volume; namely, the chapter A vueltas con el Estado del bienestar: espacios de autonoma y desmercantilizacin, from the collective effort Espabilemos! Argumentos desde el 15-M (Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata, 2012); the epigraph Un capitalismo en corrosin terminal, from my book Espaa, un gran pas: Transicin, milagro y quiebra (Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata, 2012); the text Ciudadanismo y movimientos sociales, which appeared in the May 2013 bulletin of the Fundacin Anselmo Lorenzo; and the articles La CNT cumple cien aos, Los modelos latinoamericanos: una reflexin libertaria, and Por qu hay que construir espacios autnomos, which I have published on my website, www.carlostaibo.com, in October 2010 and in April and May 2013, res pectively.

Ca rlos Taibo

Libertari@s. Antologa de anarquistas y afines para uso de las generaciones jvenes (Barcelona: Del Lin ce, 2010).