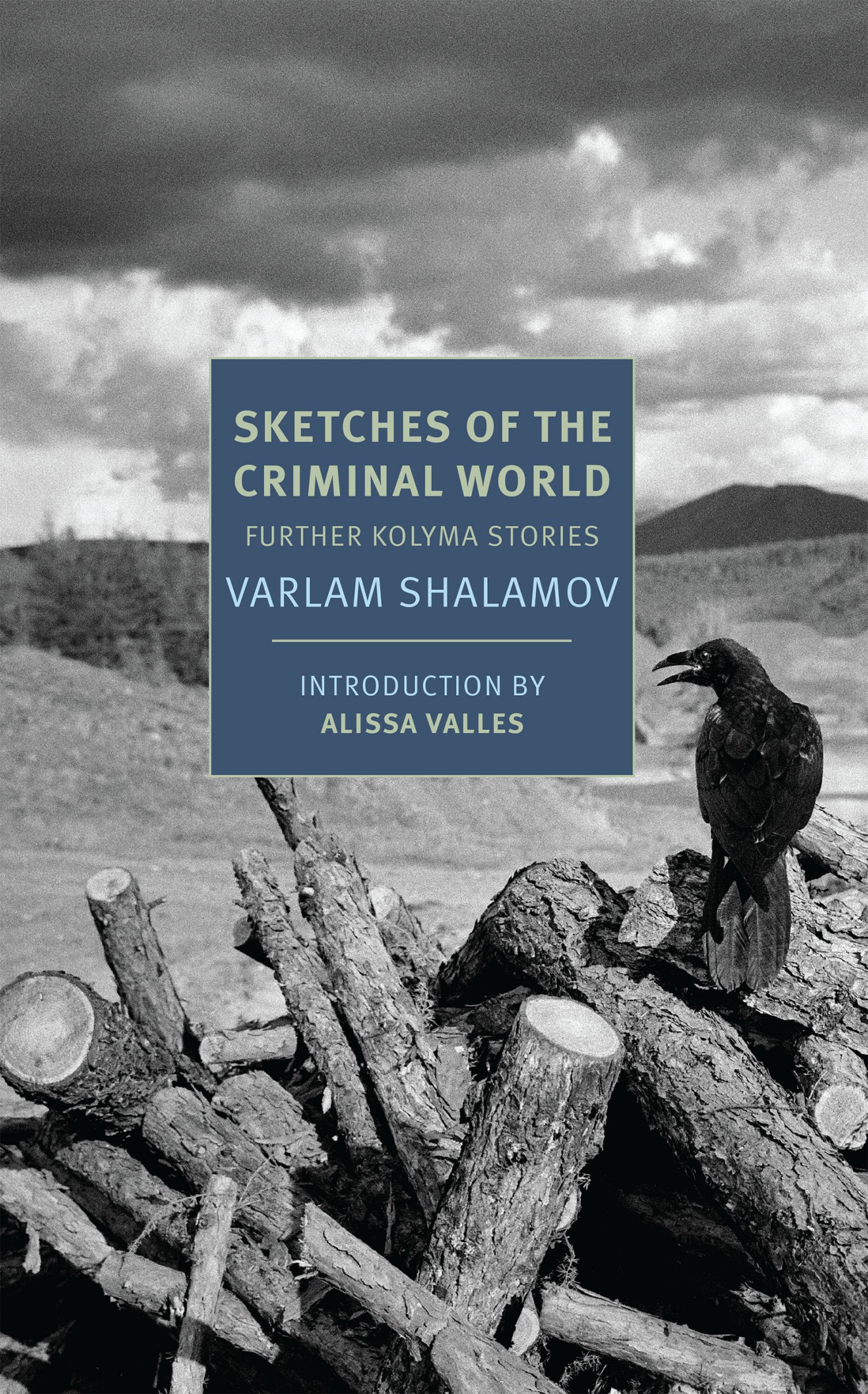

Varlam Shalamov - Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories

Here you can read online Varlam Shalamov - Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

VARLAM SHALAMOV (19071982) was born in Vologda in western Russia to a Russian Orthodox priest and his wife. After being expelled from law school for his political beliefs, Shalamov worked as a journalist in Moscow. In 1929, he was arrested at an underground printshop and sentenced to three years of hard labor in the Ural Mountains, where he met his first wife, Galina Gudz. The two returned to Moscow after Shalamovs release in 1931; they were married in 1934 and had a daughter, Elena, in 1935. Shalamov resumed work as a journalist and writer, publishing his first short story, The Three Deaths of Doctor Austino, in 1936. The following year, he was arrested again for counterrevolutionary activities and shipped to the Far North of the Kolyma basin. Over the next fifteen years, he was moved from labor camp to labor camp, imprisoned many times for anti-Soviet propaganda, forced to mine gold and coal, quarantined for typhus, and, finally, assigned to work as a paramedic. Upon his release in 1951, he made his way back to Moscow where he divorced his wife and began writing what would become the two-volume Kolyma Stories. He also wrote many books of poetry, including Ognivo (Flint, 1961) and Moskovskiye oblaka (Moscow Clouds, 1972). Severely weakened by his years in the camps, in 1979 Shalamov was committed to a decrepit nursing home north of Moscow. Following a heart attack in 1980, he dictated his final poems to the poet A.A. Morozov. In 1981, he was awarded the French PEN Clubs Liberty Prize; he died of pneumonia in 1982.

DONALD RAYFIELD is Emeritus Professor of Russian and Georgian at Queen Mary University of London. As well as books and articles on Russian literature (notably A Life of Anton Chekhov), he is the author of many articles on Georgian writers and of a history of Georgian literature. In 2012 he published Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia, which has recently come out in an expanded Russian edition, as have his A Life of Chekhov and Stalin and His Hangmen. He was the chief editor of A Comprehensive Georgian-English Dictionary. He has translated several novels, including Hamid Ismailovs The Devils Dance from the Uzbek and Nikolai Gogols Dead Souls (an NYRB Classic), as well as Varlam Shalamovs Kolyma Stories (an NYRB Classic).

ALISSA VALLES is the author, most recently, of the poetry collection Hospitium. Her translations include Zbigniew Herberts Collected Poems and Collected Prose, Ryszard Krynickis Our Life Grows (NYRB Poets), and Jzef Czapskis Memories of Starobielsk, forthcoming from NYRB Classics in 2020.

E very story of mine is a slap in the face of Stalinism, Varlam Shalamov wrote to his friend Irina Sirotinskaya in 1971, and like any slap in the face, has laws of a purely muscular character. He returns to the idea a little later in the letter, contrasting his own ideal of prose to the expansive spade work of Tolstoy: A slap in the face must be short, resonant. Most of Shalamovs stories are indeed short, some extremely so, and constitute an argument both with the great nineteenth-century Russian novels and with the wretched ones of the Stalinist era that sought to pour the pap of socialist realism into a pseudo-epic form. The slap works simultaneously as a figure for aesthetic form and political protest, and in Shalamovs late essays and letters, it functions as a motto of sorts, a creed of laconic defiance echoing, distantly, the Russian futurist manifesto A Slap in the Face of Public Taste andmore intimately and immediatelythe famous opening of Nadezhda Mandelstams memoir Hope Against Hope: After slapping Aleksey Tolstoy in the face, M. immediately returned to Moscow.

Mandelstam sent the manuscript of her memoir about life with the poet Osip Mandelstam to Shalamov in 1965, and while neither could hope to publish their prose in the Soviet Union at that time, the two established in the correspondence that followed a shared sense of purpose. He writes: If I had to give a literature course on the second half of the twentieth century, I would start by burning all the textbooks on the podium, in front of the students. The link between eras, between cultures has been broken; the exchange has been interrupted and our mission is to pick up the ends of string and tie them back together. She replies: I dont think we should burn textbooks: its too classical a gesture... Lets just not use any; her main concern, too, she writes, is the link that connects one era to another, the only thing that allows society to be human, a human being to be human.

The task Shalamov took on as a writer was what Osip Mandelstam in the celebrated and chilling poem The Age (Vek) figured as piecing together the broken back of an animal.

My age, my beast, who will look you

straight into the eye

And with his own life blood fuse

Two centuries vertebrae?

Shalamov conceives of his writing not only as an act of witness (to a crime) but also as an act of healing or at least of treating an illness or injury. The crimes of Stalinism were committed by a country against itself, in a self-consuming process by which each generation of executioners soon became the next group of victims. Giving an account of the Gulag means finding a form for a suicidal cycle of alienation and death. What is being documented has no end, either logically (since to rid the Soviet state of all its possible enemies Stalin would have had to exterminate every single citizen) or historically (there was no liberation of the camps, no formal end to the system, even after Stalins death and Khrushchevs denunciation). The literary means to find an escape from a vicious cycle is necessarily elliptical. A narrative slap in the face, as opposed to a physical one, is the opposite of mimetic violence: it is a transformation of pain into artistic forma form that, like a set fracture, makes the bone stronger than it was before.

But the Stalinist years brought with themalong with the torture, starvation, and destruction of millions of human beingsan assault on language that systematically subverted and diminished the power and viability of words. To resurrect the dead in living memory Shalamov had to bring words back into an organic relation with reality. He found help in the Acmeist movement to which Mandelstam had belonged, the work of a group of poets reacting against the mystical vagaries of symbolism and striving to plant poetry firmly back in the soil of the physical, perceptible world. The essays that Shalamov wrote alongside his stories in the 1950s and 60sincluding one titled Diseases of Language and Their Treatmentare his continuation of that struggle. In their polemical, battle-ready tone and their call for a new prose equal to the new crisis conditions of Soviet life, they bring to mind the manifestos of the prewar avant-garde. Challenge and disputation are methods of tying the ends together no less than reverence and emulation.

Shalamovs insistence on the direct participation of literature in life has its roots in the 1920s, when he was a student and, briefly, a journalist in Moscow. Few environments in modern history can have been more exciting to an aspiring writer than the Moscow of those years, a revolutionary city teeming with artistic movements, publications, performances, and quarrels. The futurist movement, the radical formal explorations of the journal LEF, and slightly later Novyi LEF and its promotion of factography, all had a profound appeal for Shalamov, who sincerely believed in the aim of raising millions out of illiteracy and out of the poverty he himself had known growing up in Vologda. Inclined to believe in the place of art in that struggle, he spent several years exploring the contending ideas of art as political instrument and the work of art as a sovereign creation.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories»

Look at similar books to Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Sketches of the criminal world : further Kolyma stories and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.