As a young uniformed constable, I was encouraged by my boss to apply for the detective training course at the police college in Chelmer. It was an exciting and challenging course that, if successfully completed, could lead to a sought-after posting at the Criminal Investigation Branch.

I was accepted and began the course in March 1974. Guest speakers gave lectures about all areas of policing: breaking and entering; homicide; fraud; auto theft; and vice. One of our lecturers was Detective Sergeant Jack Herbert of the Licensing Branch. Tall, well-groomed and immaculately dressed, he captivated the room as soon as he walked in. All of us looked up to him.

Herbert gave an impressive lecture, emphasising that if we wanted to join the CIB we would have to apply ourselves and diligently pursue our goal. Of all the qualities we would need to have, the one he stressed most was loyalty to the people we served with.

Before the end of the year I learnt that Jack Herbert had retired from the police force on medical grounds. The next time I heard Herberts name mentioned was more than a decade later in the Four Corners report entitled The Moonlight State, which named Herbert as the bagman who collected bribes for corrupt police.

I often think back to that lecture he gave at the police college in 1974. Was Herbert sizing us up, wondering which of us he would one day be able to recruit into his network of crooked detectives? As the only Indigenous man in the room, I reckon I would have stuck out. One way or another, I usually have.

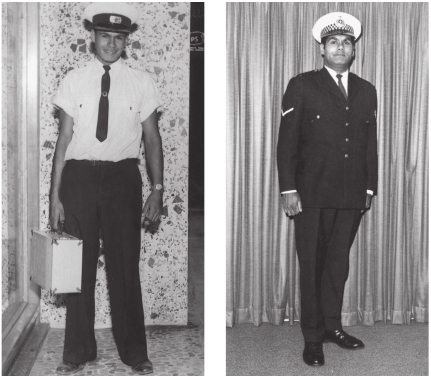

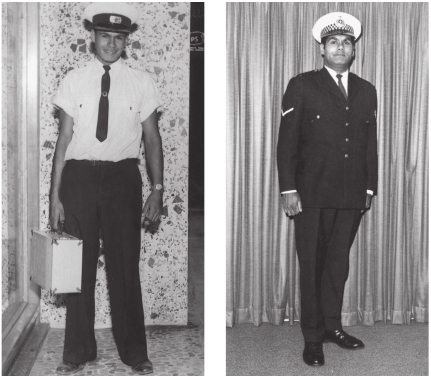

(Left) Aged sixteen and studying first aid.

(Right) Constable First Class, aged twenty-five

Me and a friend. Im seventeen years old and the world is ahead of me.

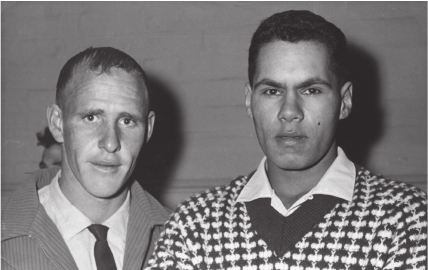

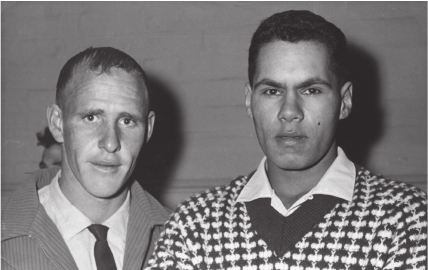

(Left) With my two children, Sandra and Anthony.

(Right) On the set of Police State, 1989.

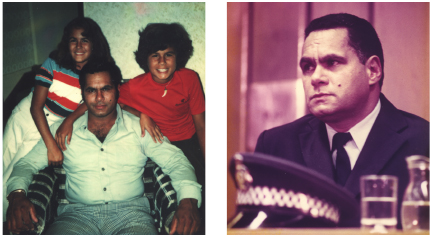

Outside my barristers chambers after giving evidence

to the Fitzgerald Inquiry, 17 September 1987.

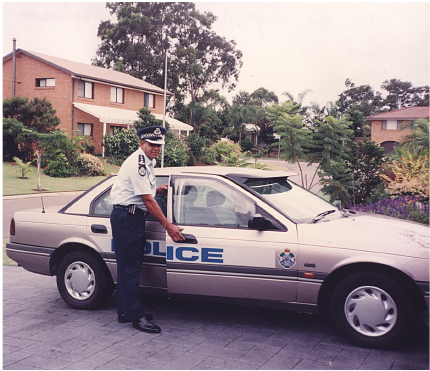

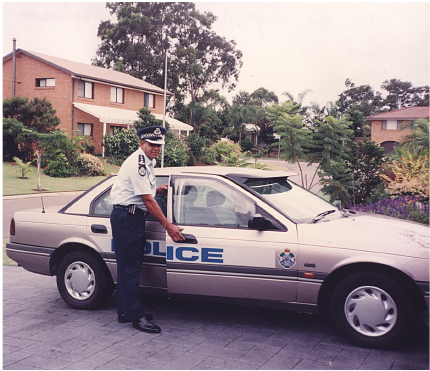

An inspector in the Professional Standards Unit, 1991.

Just before my retirement.

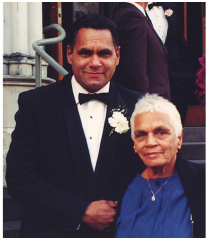

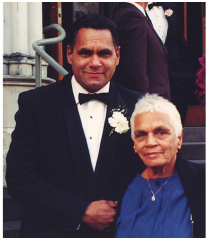

With my mother, who gave me the

ethical framework and resilience

to stand up to corruption in the

Queensland Police Force.

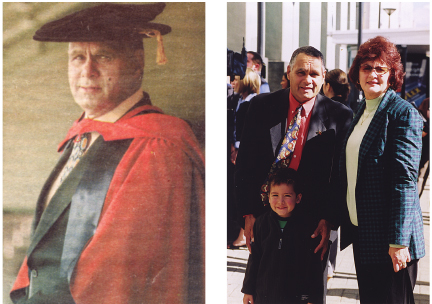

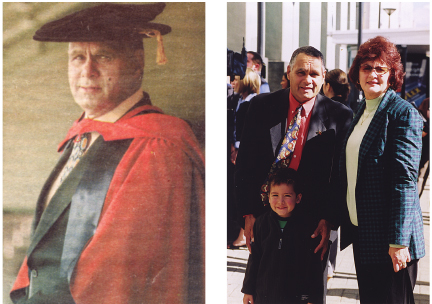

(Left) From my clipping folder. Receiving an honorary

doctorate from Queensland University of Technology, 2000.

(Right) With Linda and my grandson Jackson.

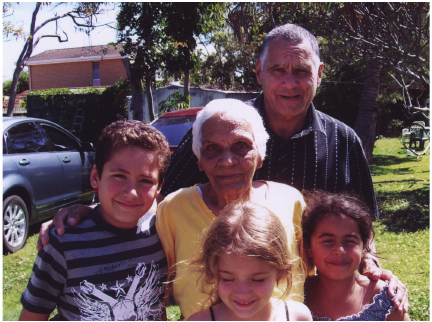

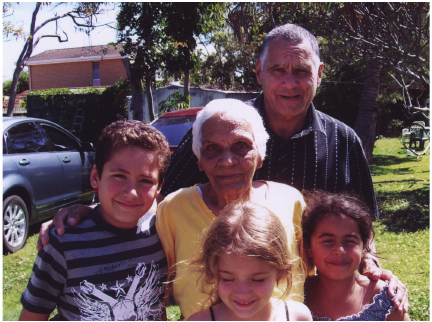

In happy retirement, with Mum and my three grandchildren,

Jackson, Ashleigh and Magnolia.

I contacted the Fitzgerald Commission of Inquiry by telephone on Wednesday, 9 September 1987, the day after being discharged from Prince Charles Hospital, Brisbane where I had undergone heart surgery. After stating my name, address, rank and where I was stationed, I said that I wanted to come in to talk about my time at the Licensing Branch. The person who answered said that I would be contacted in due course but that it was not possible to give me a date. It seemed to me that he didnt care whether I came in or not. The lukewarm response was a bitter disappointment after all the agonising that had gone into my decision to make the call. I consoled myself with the thought that other honest cops would soon be coming forward to tell the commission what they knew about corruption in the Queensland Police. Little did I know that most of the honest cops would remain silent.

Detective Senior Sergeant Harry Burgess, who was up to his neck in corruption, had already confessed to taking bribes. As a result of Burgesss admissions, on 31 August 1987 Commissioner Fitzgerald had declared that the issue is no more whether there was any corruption as how much and by whom. He went on to say:

This inquiry is going to succeed with or without the information provided by honest policemen. Without that information it may be harder and it may take longer but the result will be the same We are quite aware of the desperate campaign which is being waged within the force to seek to maintain the closed ranks which provide a shelter for any culprits.

I did not need Fitzgerald or anyone else to tell me what it would mean to break ranks. I hadnt slept properly for weeks. My stress levels were through the roof. I had recently suffered a near-fatal heart attack and was still recuperating from follow-up heart surgery. I had been inside enough courtrooms to know that once I was in the witness box I would be subject to relentless cross-examination by lawyers being paid to destroy my credibility. I knew that the people I was accusing of corruption would do everything they could to intimidate me. When the moment of truth came, would I stand strong or would I buckle? I really didnt know.

At about 8 p.m. on Sunday, 13 September 1987 I was surprised to hear a knock at my front door. I answered and was greeted by Ralph Devlin, junior counsel assisting the Fitzgerald Inquiry. He hadnt bothered to telephone me beforehand to let me know he was coming. We went upstairs to my study where Devlin told me that he had come to take a statement from me about my service at the Licensing Branch. He had brought an A4-sized writing pad on which he scribbled notes. I told him that it would be far better for me to be interviewed at the commissions offices where I could givemy statement and have it typed up in one go, but Devlin explained that the commission was short-staffed and that the only way they could keep on top of their work was by interviewing witnesses at weekends.

I remember saying to him that I hoped other police were coming forward to give supporting evidence of corruption, because without their corroboration it would be impossible to flush out the system.

Devlins response was, Dont worry, Col. Youve got a lot of mates following you.

Talking to Ralph Devlin at home in my study was one thing, but the thought of giving evidence in public was giving me the terrors. I told Devlin I was worried about my health. The pressure was killing me. I said I needed a couple of weeks to pull myself together before giving evidence and Devlin gave me the impression that the commissioner was prepared to wait. Two days later I received a call from a lawyer called Pat Nolan, representing the Queensland Police Union of Employees. He said, Col, I have been contacted by the senior staff at the inquiry and they have advised me that they need you to appear and give evidence tomorrow.

Next page