SHE GOES TO WAR

For my late father Inder Sahai, who instilled in me a love for the written word and a spirit of enquiry, subsequently rejoicing when I broke into what was then an all-male citadelthe newsroom of an English dailyto become a reporter.

AND

For my grandson Ayaan, who at six, is already quite a wordsmith!

Contents

Authors Note

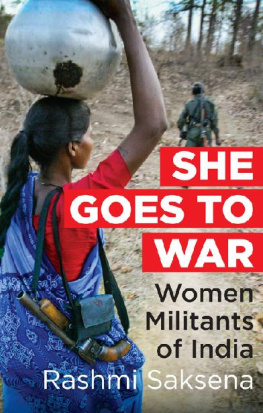

THEY STARTED TO CROSS MY PATH IN THE MID 1990s. AS I chased news stories across the country, ranging from political to human interest, they were there. They came in various avatars. Killers, victims, mercenaries, lured innocents, misguided youth, double agents and even as the bewitched following their love to the end. On dusty trails of election campaigns across regions of Madhya Pradesh, now renamed Chhattisgarh, they were the girls the rebel Maoists had drafted into their cadres. In the remote villages of the earthquake-devastated Kashmir Valley they were conduits for Pakistan-based terror groups routing money, blankets and food to the devastated, to show sympathy for the locals. In Andhra Pradesh they were pragmatic daughters of starving handloom weavers who had exchanged a kitchen fire gone cold for two square meals in the forest camps of outlawed Naxals. At times they were the bold ones who had taken up the gun for an ideological armed struggle to overthrow elected authority. They stood large in the ranks of resistance movements in Indias northeastern states of Assam, Manipur and Nagaland.

They stared down at me from posters pinned to trees or stuck to walls of ramshackle tea shops. They looked up at me from stamp-size photographs in musty police files. They jumped out of itsy-bitsy newspaper reports. They cropped up in my conversations with administrators, security personnel and intelligence gatherers. They brushed past me in courtrooms. They demanded attention as protagonists in local tales of suspicious activity, spunk and romance. Tantalizing as they were, I could not go after them simply because they were not my story of the day. Or should they have been? After following the news flash of the assassination of former Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, I had worked frantically to garner details of Dhanu, his assassin. She was the first known human bomb in India. I had barely spent a day on the 24-year-old when it emerged that she was an LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam) operative. The story moved out of my city. I was left wondering what this woman, who had so calmly bent down to touch Rajiv Gandhis feet seconds before detonating the belt of explosives hidden in her kurta and hours earlier had devoured a huge portion of her favourite chicken biryani, was really like. I had also noted that another woman, Nalini, was an accomplice and standby at the Sriperumbudur site of the assassination.

I had also made a mental note of the alleged role of a Kashmiri woman, Farida Dar, in the May 1996 bomb blast in New Delhis busy Lajpat Nagar area and of another Srinagar-based woman, Anjum Zamarud Habib, who had stirred a diplomatic crisis when she was apprehended in February 2003 after she had allegedly been given money by a senior diplomat in the Pakistan High Commission to fund terrorist groups in the Valley. Stored away in my minds file on women militants operating in India was Ishrat Jahan who was killed by the police on the outskirts of Ahmedabad, Gujarat, on 15 June 2004. According to the police she was part of a team planning to kill Prime Minister Narendra Modi then the chief minister of Gujarat. Later it was alleged that she could well have been a suicide bomber working on orders of the Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), the Pakistan-based terror group known to target India.

However sketchy my introduction to women insurgents in India had been, I could not forget these figures lurking in the shadows. They refused to be trashed from memory as redundant information picked up on my journalistic travels. Their brief mentions, references made in passing and their sketchy stories were like enticing blurbs of a book or the trailer of a mystery movie or a new drink aggressively advertised, beckoning to be savoured when time permitted. I flagged them to pursue some day.

I began my chase in August 2015 just before women militants started to make international headlines as never before.

The generic term, women militants, told me little about them as persons or the lives they led. What I had read or heard about them had merely boxed them under the terrorist label. I was curious to discover the person behind a bomb explosion, an ambush, a courier ferrying arms or missives and delivering recruitment spiels. I was fascinated by these women who were trekking an unconventional path from the gender point of view, considering that they came from traditional backgrounds and social milieu. I wanted to meet them and ask them umpteen questions that would help me understand them as persons. Why had they traded the security of home and family for a life of risk and physical hardship? Were they rebels against a system that put them in a slot? Was it really a choice to break out of the traditional societal mould cast for them or was it merely coming to terms with an existence in which options were a luxury they could not afford? Were they romantics heady on ideology or simply free-spirited adventurists? What or who had motivated them to exchange the sari for army fatigues? Was it money, fear or favour done for a dear one? Did they know what they had bargained for when they took up the gun, committed to kill on order and put their lives on the line as they carried out assigned tasks? What for them fell in the line of duty? Were they aware of the fate that awaited them if apprehended, arrested and convicted? Did they know how vulnerable they were, once on the radar of law enforcement agencies? What was life like in the cadre of an underground organization? Did it mean empowerment and status as equals with the men, something which had eluded them in life over-ground? Were they heroines for their families and people they had left behind back home or viewed as women gone astray? Was joining banned movements a one-way street? What did going back hold for them?

When I began my search for women from underground outfits they became as elusive as they had been obvious before I went looking for them. I returned to those who had spoken about them but the leads went cold. The girls were either lost to them or dead. But I did get lucky in a few cases. My chase took me to places still in the grip of insurgency as well as those where it was petering off. Here I came up against a wall. Those who knew of one-time women insurgents did not want to point them out for fear of treading on toes or courting trouble from active outfits. The code of conduct was live and let live. The one-time players seemed determined to let their monochromatic present mask their colourful past. Painstakingly, I searched police and court records, worked sources and, using them as links in a chain, established contact with about 100 women from the ranks of resistance movements in Kashmir, Chhattisgarh, Manipur, Assam and Nagaland. I enjoyed getting to know them, hearing their stories, and the time spent with them. I have selected sixteen profiles because each represents a different personality and highlights the varied sort of work they do as women militants.

Tracing them was only part of the two-year exercise. The bigger challenge was to get them talking. Suspicion and caution were what they had lived and survived by underground. It was ingrained in them and had become part of their personality. Even when I saw a chink in their protective cloak, holding promise of their opening up, it often disappeared quickly. But once they started to ask me questions about myself I knew I stood a chance. I knew they were checking me out...a habit cultivated during days of hiding. When I passed scrutiny it was always rewarding. Over many meetings, they shared their stories with no full stops. I am grateful to these women for letting me into their world which they have now put behind them, some with regret, others, happily. Their stories and the texture of their personalities vary, but the single dominant trait they have in common is to fearlessly take a chance. They did it with me. With no one to stand guarantee that I was not there to sell them out, they looked me over and agreed to be part of my book. I hope I have not let them down when I paint their portraits.