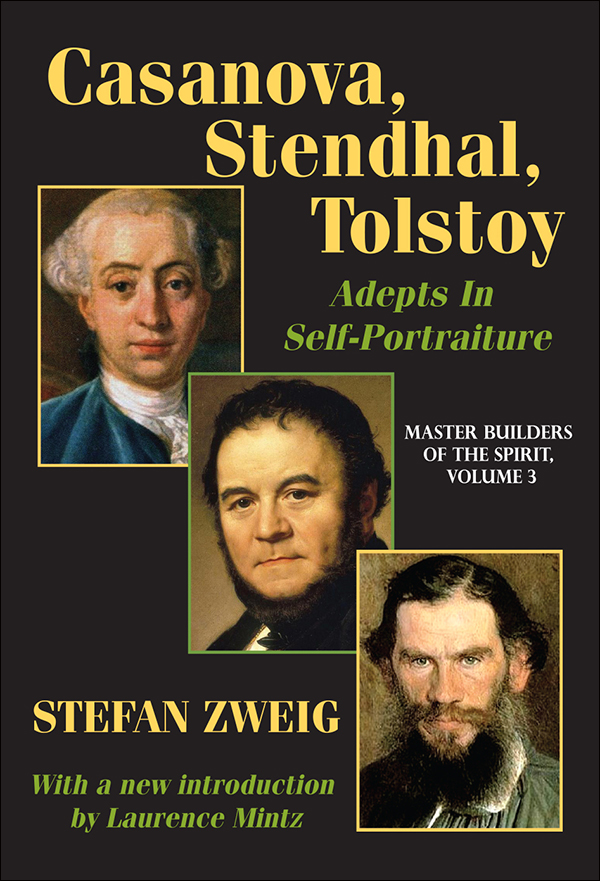

Zweig - Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture

Here you can read online Zweig - Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2012, publisher: Taylor & Francis (CAM), genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture

- Author:

- Publisher:Taylor & Francis (CAM)

- Genre:

- Year:2012

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Zweig: author's other books

Who wrote Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Casanova,

Stendhal,

Tolstoy

Stendhal,

Tolstoy

Adepts In Self-Portraiture

MASTER BUILDERS OF THE SPIRIT, VOLUME 3

STEFAN ZWEIG

With a new introduction by Laurence Mintz

Originally published in 1929 by Allen & Unwin

Published 2012 by Transaction Publishers

Published 2017 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

New material this edition copyright 2012 by Taylor & Francis.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 2011039504

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zweig, Stefan, 1881-1942.

[Drei Dichter ihres Lebens. English]

Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy : adepts in self-portraiture : master builders of the spirit / Stefan Zweig (new introduction by Larry Mintz).

p. cm. -- (Master builders of the spirit ; 3)

ISBN 978-1-4128-4595-3 (acid-free paper)

1. Casanova, Giacomo, 1725-1798--Criticism and interpretation.

2. Stendhal, 1783-1842--Criticism and interpretation. 3. Tolstoy, Leo, graf, 1828-1910--Criticism and interpretation. 4. Self in literature. 5. Autobiography--Authorship. I. Title. II. Title: Adepts in self-portraiture.

PN514.Z82413 2012

809'.93592--dc23

2011039504

ISBN 13: 978-1-4128-4595-3 (pbk)

"Safety first!" Moritz Zweig

"There is no safety."Arthur Schnitzler, Paracelsus

I N the decades between the two world wars, Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) was probably the most widely translated and read "serious" author in the world. He was the writer who most thoroughly embodied the popular image of "the good European" and the ideals (as they were then conceived) of humanist universalism and apolitical internationalism. Amazingly prolific, his indefatigable activity as fiction writer, poet, essayist, biographer, translator, dramatist, librettist, and cultural ambassador at large was driven by a fervent, near religious faith in the supranational unity of Western culture that bore its finest fruit in the Renaissance humanist and Enlightenment values of reason, tolerance, progress, peace, and the intellectual figures who personified them while facing down their enemies.

The cultural readjustments of the postwar years changed all of that. Zweig's reputation and popularity, at least in the English-speaking world (he has always been popular in France) dwindled along with those of such now dusty names as Jules Romains, Ren Schick-ele, Georges Duhamel, Lion Feuchtwanger, Jakob Wassermann, Henri Barbusse, and Romain Rolland.

Most of his books went out of print, and he was remembered mainly for a single short story, "Letter From an Unknown Woman," the source of Max Ophuls' great film of the same title; thus, his name became associated (somewhat misleadingly) with the alt Wien of Strauss music, moonlit walks in the Prater, cafes, closed fiacres, and chambres separes. His Viennese friends and contemporaries, Arthur Schnitzler, Joseph Roth, and Hugo von Hofmannsthal suffered a similar eclipse, but in the case of Zweig this had less to do with literary fashion than with his very public role as literary statesman and the dated, naive quality of his above-the-fray idealism in the shadow of the war's devastation, the Holocaust, and the ideological battles of the Cold War.

Something of Zweig's postwar fall from grace was anticipated in Hannah Arendt's scornful review (1943) of his posthumously published memoir, The World of Yesterday. Zweig, together with his second wife, had committed suicide in Brazilian exile, a gesture of despair that unsettled and angered the German migr community. Thomas Mann, the erstwhile unpolitischen, now its unofficial leader, had turned all his extra-literary efforts to the fight against Nazism, and refused to write more than a perfunctory tribute, considering Zweig's act a dereliction of duty. By contrast, Arendt, then at the height of her Zionist commitment, went after Zweig without mercy, portraying him as an ivory tower aesthete who regarded Nazism first and foremost as an affront to his personal dignity and privileged way of life. Lacking any coherent political viewpoint, he is unable in his recollections, she charged, to trace the chain of causality from the false security of the late Habsburg decades to the present catastrophe. His blinkered portrayal of Viennese life, in Arendt's view, hardly ventures beyond the closed circle of its cultivated bourgeoisie with its even more circumscribed and oblivious Jewish component. She views with contempt the generational transition from money making to cultural activity among Jewish families (which Zweig records with defensive pride) as a regressive retreat from worldly responsibility and knowledge. In its place, Arendt, like the Viennese critic Karl Kraus, sees, not the cultural renaissance Zweig claimed, but a sham theatrical culture of aesthetic surfaces and actorly gestures, not greatness but the image of greatness, a portent of Hollywood.

There is some rough justice to Arendt's criticism, but her portrayal of Zweig departs markedly from both the tone and substance of his memoir. (A small example: Zweig does not praise Karl Lueger, the anti-Semitic mayor of Vienna as "'an able leader' and kindly person." Like every subsequent historian of Vienna, he acknowledges Lueger's undeniable political skills, but emphasizes that underneath the suave exterior der schdne Karl was Hitler's prototype with his own Streicher, "a certain mechanic named Schneider.") At points, Arendt elides her ostensible subject to create a composite figure of the typical Viennese-Jewish intellectual caring only for fame and success and who may or may not be identifiable with Zweig. Thus,

[c]ontemporary success was also the only criterion that remained for the "general geniuses," detached from their achievements and considered only in light of their "inherent greatness." In the field of letters this took the form of biographies describing no more than the appearance, the emotions and the demeanor of great men. This approach not only satisfied vulgar curiosity about the kind of secrets a man's valet would know; it was also prompted by the belief that such idiotic abstraction would clarify the essence of greatness.

Zweig was, of course, famed for his best-selling biographies of "great men," but these books (the Master Builders trilogy in particular) intended to distill the creative psychology and historical significance of their subjects. Personal trivia and gossip of the sort to debunk the subject (the Great Man is not so great) or flatter the reader (the Great Man is just like me) are not to be found.

Something in Arendt's tone suggests a north German contempt for the Viennese and the condescension of the philosophic mind for the "merely" artistic, but when she points to Zweig's failure to recognize the significance of Kafka and Brecht in the post-WWI years ("They were not successes") she correctly discerns in him an intellectual conservatism or reserve that was unable to embrace the more aggressive, adversarial, or ambiguous currents of what came to be seen as characteristically modernist, and thus left him at a disadvantage in the cultural reckoning to come. This, in turn, reflects what was until fairly recently the comparative outsider status of Viennese art, literature, and music in the grand and rather exclusivist narrative of high modernism.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture»

Look at similar books to Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Casanova, Stendhal, Tolstoy: Adepts in Self-Portraiture and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.