The right of Euripides Altintzoglou to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Routledge Advances in Art and Visual Studies

This series is our home for innovative research in the fields of art and visual studies. It includes monographs and targeted edited collections that provide new insights into visual culture and art practice, theory, and research.

Contemporary British Ceramics and the Influence of Sculpture

Iconoclasm, Monument, and Multiples

Laura Gray

Contemporary Citizenship, Art, and Visual Culture

Making and Being Made

Edited by Corey Dzenko and Theresa Avila

The Evolution of the Image

Political Action and the Digital Self

Edited by Marco Bohr and Basia Sliwinska

Artistic Visions of the Anthropocene North

Edited by Gry Hedin and Ann-Sofie N. Gremaud

Contemporary Artists Working Outside the City

Creative Retreat

Sarah Lowndes

Design and Visual Culture From the Bauhaus to Contemporary Art

Optical Deconstructions

Edit Tth

Changing Representations of Nature and the City

The 1960s1970s and Their Legacies

Edited by Gabriel Gee and Alison Vogelaar

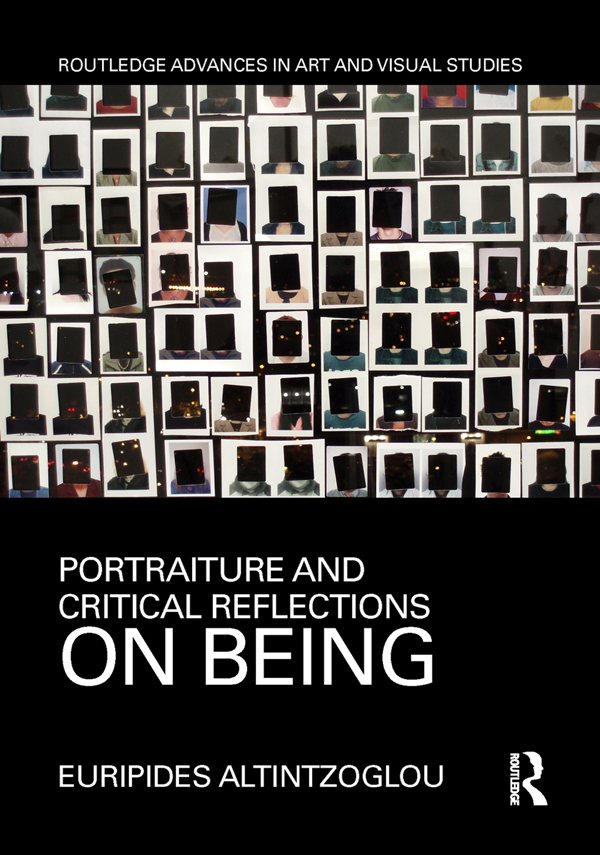

Portraiture and Critical Reflections on Being

Euripides Altintzoglou

For a full list of titles in this series, please visit www.routledge.com/Routledge-Advances-in-Art-and-Visual-Studies/book-series/RAVS

Contents

Guide

Portraiture and Critical Reflections on Being

This book analyses the philosophical origins of dualism in portraiture in Western culture during the classical period, through to contemporary modes of portraiture. Dualismthe separation of mind from bodyplays a central part in portraiture, given that it supplies the fundamental framework for portraitures determining problem and justification: the visual construction of the subjectivity of the sitter, which is invariably accounted for as ineffable entity or spirit, that the artist magically captures. Every artist who has engaged with portraiture has had to deal with these issues and, therefore, with the question of being and identity.

Euripides Altintzoglous practice explores the correlation of being, politics, and change. He is the co-editor (with Martin Fredriksson) of Revolt and Revolution: The Protester in the 21st Century (Oxford, UK). His work has been exhibited internationally in private galleries, public museums, and biennales. He currently holds the post of Senior Lecturer in Fine Art and Photography at the Wolverhampton School of Art est. 1851, University of Wolverhampton.

There are a number of factors that must be considered in analysing a portrait in order to establish its meaning: the historical conditions within which the work is produced; the representational intentions and social identities of the artist and sitter; the conventions of the portrait; and its context of reception. We are then in a position to ask: has the artist created a reasonable likeness, an idealisation, or a counterfeit image of the subject? Has the artist incorporated a hidden symbolism, or biographical referencessuch as the subjects profession or social class, or for instance, their allegiance to a cause, principle, or ideology? Knowing these things, we can then surmise what the likely function of the portrait is, its relationship to other works of a similar kind, and the relationship between the artist and the person represented. My work on the place and function of the portrait in pre-modernist, modernist, and postmodernist art will apply these kinds of analyses to a range of works, paying specific attention to the demise of the traditional monadic and painted academic portrait and the rise of the multiple and allegorical installation-based portrait. In doing so it will attempt to map the development of portraiture in relation to the philosophical position of dualism, and its subsequent modifications and rejection.

The traditional, academic portrait has clearly been subject to various forms of denaturalisation over the last hundred years, but it is only with the incorporation of photography, and text, into 1960s avant-garde art, and as such its rejection of the expressive model of representation generally, that the claims of the traditional portrait to reflect or mirror the identity of the sitter have been questioned in any explicit fashion, producing a widespread critique of the Cartesian self. These transformations have brought into being new forms of portraiture and new kinds of working relationships between the artist and the person depicted, and new accounts of the representation of subjectivity in art. In this respect, an understanding of the history of the dualist portrait format is absolutely crucial in understanding the extensive turn to the representation of subjectivity in contemporary practice. Indeed, once portraiture is freed from conventional dualist modes of representation in the conceptual art of 1960s, portraiture dissolves itself into a discursive politics of the self.

The first chapter of this book offers a historical overview of the origins and development of the Western portrait, beginning with the Egyptian and Greek portrait and stretching to the Renaissance. In doing so, it focuses initially on a selection of Greek and Christian myths of the origins of the portrait, in an effort to underpin the role and function of the portrait in these cultures. The emergence of the Western portrait is presented through an analysis of the key notions of the honorific and exemplary in classical portraiture, which derive from Platonic and Aristotelian positions on art. In this respect, the Hellenistic and Roman employment of portraiture as forms of self-promotion is reviewed in relation to the Aristotelian notion of idealisation. Similarly the abstraction of the figure in Byzantine art is examined in relation to the Platonic origins of the Christian prioritisation of the spiritual. These two fundamental positions form the basis for the subsequent analysis of religious, state, and humanist portraiture during the Renaissance.

In addition, the first chapter traces the philosophical origins of Cartesian dualism in classicism, and presents an overview of anti-dualist positions, spanning from classicism to the present day. The central Cartesian notion of an eternal and immutable soul is located in Platonic philosophy, while it is discussed in relation to the Aristotelian (materialist) position of hylemorphism. Furthermore, this chapter traces the gradual assimilation of Aristotelian philosophyparticularly the unresolved question of the intellectinto the realm of Christian dogma, which led, through the work of Thomas Aquinas and Augustine of Hippo, to Descartess formation of the cogito argument. Once this framework is in place, Cartesian dualism is reviewed in relation to Lockes proto-empiricism, Hobbes and Spinozas materialism, and Humes early reductionist view of the self. This section of the chapter ends by focusing on various materialist accounts, such as Gilbert Ryles behaviourism, Derek Parfits version of reductionism, Daniel Dennetts functionalism, Charles Taylors notion of the self as a socially and culturally bounded agent, John Searles dualist materialism, and W. Teed Rockwells network theory of consciousness.