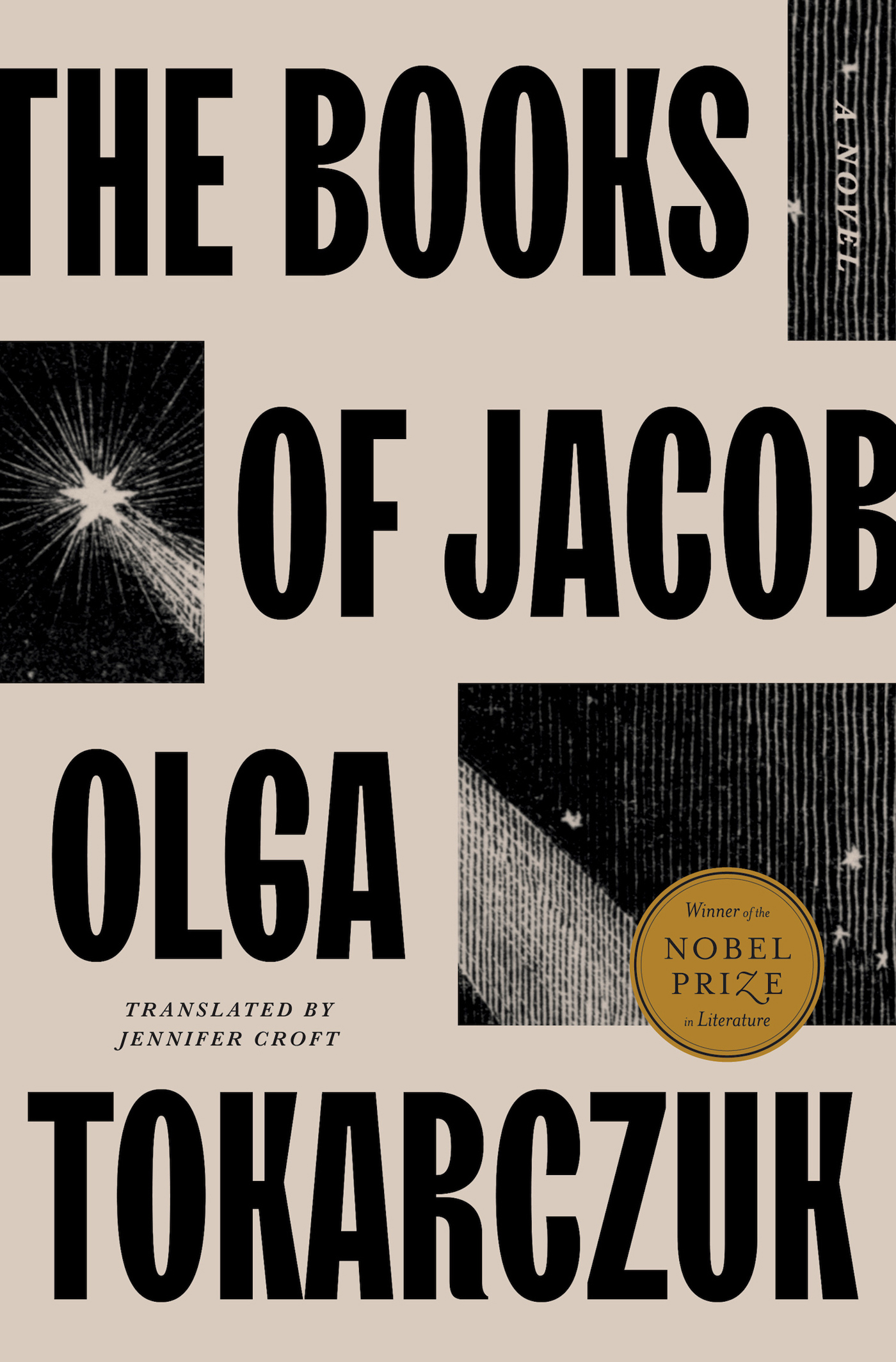

The Nobel Prize-winner Olga Tokarczuks richest and most ambitious novel yet follows the comet-like rise and fall of a messianic religious leader as he blazes his way across eighteenth-century Europe.

As new ideasand a new unrestbegin to sweep the Continent, a young Jew of mysterious origins arrives in a village in Poland. Visited by what seem to be ecstatic experiences, Jacob Frank casts a spell that attracts a fervent following. He reinvents himself again and again, converts to Islam, then Catholicism, is pilloried as a heretic, revered as the Messiah, and wreaks havoc on the conventional order, Jewish and Christian alike, with scandalous rumours of his sects secret rituals and the spread of his iconoclastic beliefs.

The story of Franka real historical figure, a divisive yet charismatic manis the perfect canvas for the genius and unparalleled reach of Olga Tokarczuk. Narrated through the perspectives of his contemporariesthose who revere him, those who revile him, the friend who betrays him, the lone woman who sees him for what he isThe Books of Jacob captures a world on the cusp of precipitous change, searching for certainty and longing for transcendence.

For my parents

Once swallowed, the piece of paper lodges in her esophagus, near her heart. Saliva-soaked. The specially prepared black ink dissolves slowly now, the letters losing their shapes. Within the human body, the word splits in two: substance and essence. When the former goes, the latter, formlessly abiding, may be absorbed into the bodys tissues, since essences always seek carriers in mattereven if this is to be the cause of many misfortunes.

Yente wakes up. But she was just almost dead! She feels this distinctly now, like a pain, like the rivers currenta tremor, a clamor, a rush.

With a delicate vibration, her heart resumes its weak but regular beating, capable. Warmth is restored to her bony, withered chest. Yente blinks and just barely lifts her eyelids again. She sees the agonized face of Elisha Shorr, who leans in over her. She tries to smile, but that much power over her face she cant quite summon. Elisha Shorrs brow is furrowed, his gaze brimming with resentment. His lips move, but no sound reaches Yente. Old Shorrs big hands appear from somewhere, reaching for her neck, then move beneath her threadbare blanket. Clumsily he rolls her body onto the side, so he can check the bedding. Yente cant feel his exertions, noshe senses only warmth, and the presence of a sweaty, bearded man.

Then suddenly, as though from some unexpected impact, Yente sees everything from above: herself, the balding top of Old Shorrs headin his struggle with her body, he has lost his cap.

And this is how it is now, how it will be: Yente sees all.

Its early morning, near the close of October. The vicar forane is standing on the porch of the presbytery, waiting for his carriage. Hes used to getting up at dawn, but today he feels just half awake and has no idea how he even ended up here, alone in an ocean of fog. He cant remember rising, or getting dressed, or whether hes had breakfast. He stares perplexed at the sturdy boots sticking out from underneath his cassock, at the tattered front of his faded woolen overcoat, at the gloves hes holding in his hands. He slips on the left one; its warm and fits him perfectly, as though hand and glove have known each other many years. He breathes a sigh of relief. He feels for the bag slung over his shoulder, mechanically runs his fingers over the hard edges of the rectangle it contains, thickened like scars under the skin, and he remembers, slowly, whats insidethat heavy, friendly form. A good thing, the thing thats brought him herethose words, those signs, each with a profound connection to his life. Indeed, now he knows whats there, and this awareness slowly starts to warm him up, and as his body comes back, he starts to be able to see through the fog. Behind him, the dark aperture of the doors, one side shut. The cold must have already set in, perhaps even a light frost already, spoiling the plums in the orchard. Above the doors, there is a rough inscription, which he sees without looking, already knowing what it sayshe commissioned it, after all. Those two craftsmen from Podhajce took an entire week to carve the letters into the wood. He had, of course, requested they be done ornately:

HERE TODAY AND GONE TOMORROW. O USE TO MILK IS YOUR SORROW

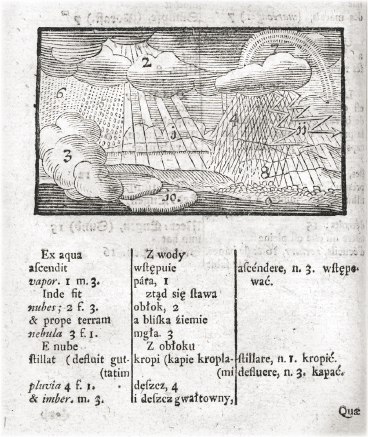

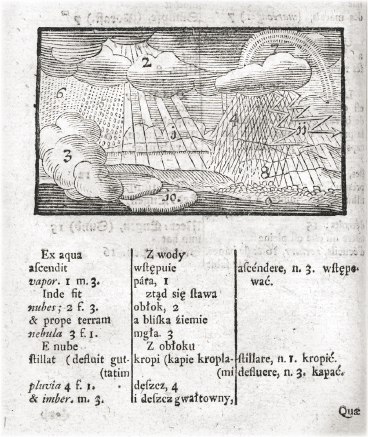

Somehow, in the second line, they wrote the very first letter backward, like a mirror image. Aggravated by this for the umpteenth time, the priest spins his head around, and the sight is enough to make him fully awake. That backward... How could they be so negligent? You really have to watch them constantly, supervise their each and every step. And since these craftsmen are Jewish, they probably used some sort of Jewish style for the inscription, the letters looking ready to collapse under their frills. One of them had even tried to argue that this preposterous excuse for an N was acceptablenay, even preferable!since its bar went from bottom to top, and from left to right, in the Christian way, and that Jewish would have been the opposite. The petty irritation of it has brought him to his senses, and now Father Benedykt Chmielowski, dean of Rohatyn, understands why he felt as if he was still asleephes surrounded by fog the same grayish color as his bedsheets; an off-white already tainted by dirt, by those enormous stores of gray that are the lining of the world. The fog is motionless, covering the whole of the courtyard completely; through it loom the familiar shapes of the big pear tree, the solid stone fence, and, farther still, the wicker cart. He knows its just an ordinary cloud, tumbled from the sky and landed with its belly on the ground. He was reading about this yesterday in Comenius.

Now he hears the familiar clatter that on every journey whisks him into a state of creative meditation. Only after the sound does Roshko appear out of the fog, leading a horse by the bridle; after him comes the vicars britchka. At the sight of the carriage, Father Chmielowski feels a surge of energy, slaps his glove against his hand, and leaps up into his seat. Roshko, silent as usual, adjusts the harness and glances at the priest. The fog turns Roshkos face gray, and suddenly he looks older to the priest, as though hes aged overnight, although in reality hes a young man yet.

Finally, they set off, but its as if theyre standing still, since the only evidence of motion is the rocking of the carriage and the soothing creaks it makes. Theyve traveled this road so many times, over so many years, that theres no need to take in the view any longer, nor will landmarks be necessary for them to get their bearings. Father Chmielowski knows theyve now gone down the road that passes along the edge of the forest, and theyll stay on it all the way to the chapel at the crossroads. The chapel was erected there by Father Chmielowski himself some years earlier, when he had just been entrusted with the presbytery of Firlejw. For a long time he had wondered to whom to dedicate the little chapel, and he had thought of Benedict, his patron saint, or Onuphrius, the hermit who had, in the desert, miraculously received dates to eat from a palm tree, while every eighth day angels brought down for him from heaven the Body of Christ. For Father Chmielowski, Firlejw was to be a kind of desert, too, after his years tutoring His Lordship Jabonowskis son Dymitr. On reflection, he had come to the conclusion that the chapel was to be built not for him and the satisfaction of his vanity, but rather for ordinary persons, that they might have a place to rest at that crossroads, whence to raise their thoughts to heaven. Standing, then, on that brick pedestal, coated in white lime, is the Blessed Mother, Queen of the World, wearing a crown on her head, a serpent squirming under her slipper.