Copyright 2012 by Robert McKimson Jr.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part or in any form or format without the written permission of the publisher.

Published by: Santa Monica Press LLC

P.O. Box 850

Solana Beach, CA 92075

1-800-784-9553

www.santamonicapress.com

Printed in the United States

Santa Monica Press books are available at special quantity discounts when purchased in bulk by corporations, organizations, or groups. Please call our Special Sales department at 1-800-784-9553.

ISBN-13 978-1-59580-069-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McKimson, Robert, Jr.

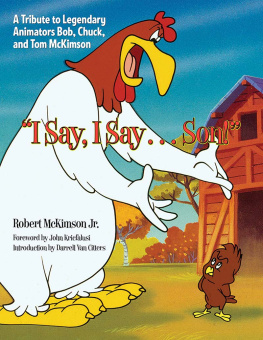

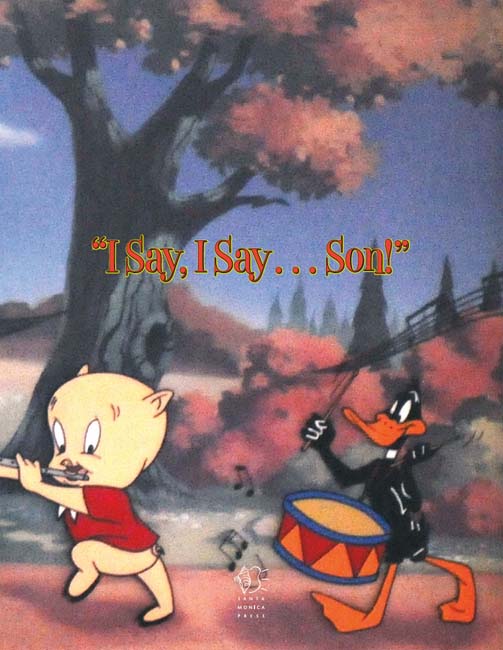

I Say, I Say Son! : A Tribute to Legendary Animators Bob, Chuck, and Tom McKimson / by Robert McKimson Jr.; Foreword by John Kricfalusi.

pages cm

ISBN 978-1-59580-069-5 (hardback)

1. McKimson, Robert, 1910-1977Criticism and interpretation. 2. McKimson, Thomas, 1907-1998Criticism and interpretation. 3. McKimson, CharlesCriticism and interpretation. I. Kricfalusi, John, 1955- II. Title.

NC1766.U52M3836 2012

741.580922dc23

2012010797

Cover image provided by Clampett Studio Collections.

Cover and interior design by Future Studio

This book is dedicated to the two women in my life:

Viola McKimson, my dear and wonderful mother, who saw to it that I was raised and schooled so I could move ahead not only in my chosen career but in life itself. I miss her every day.

Nancy, my wonder wife, whom I met late in life and who has not only supported me, but has been there whenever needed. There are not enough words to express my feelings for her.

Contents

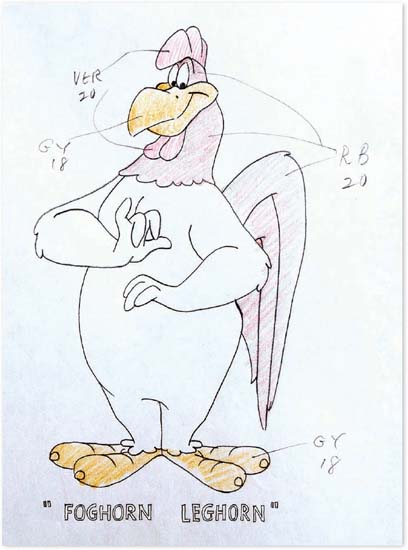

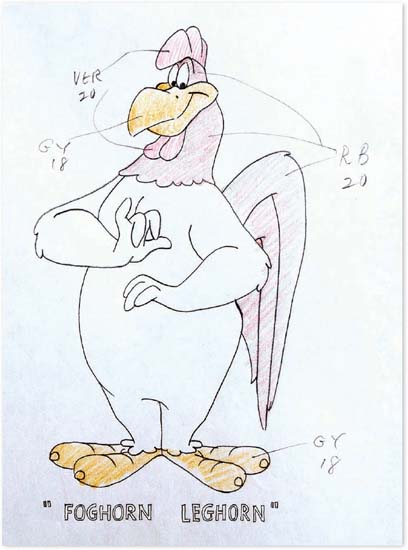

Color model drawing by Bob McKimson.

Foreword

by John Kricfalusi

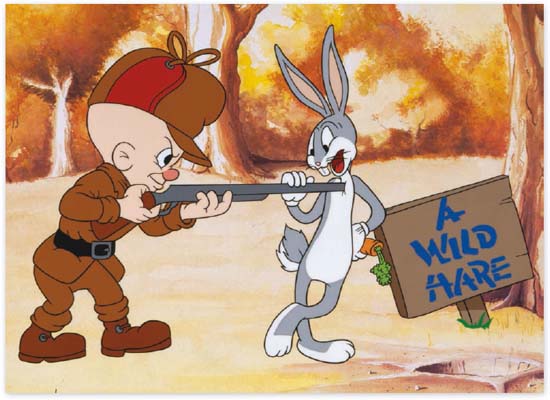

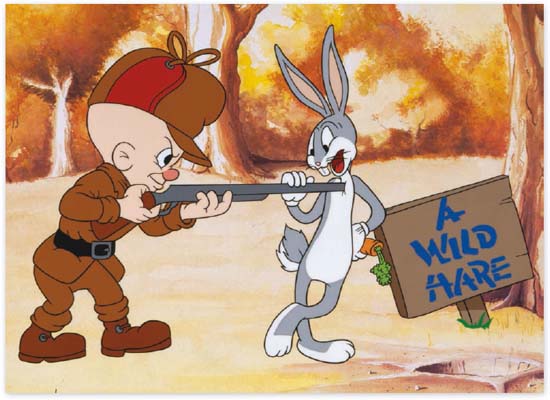

Limited edition cel from A Wild Hare (1940), with animation by Bob and Chuck McKimson.

I magine how proud you would be to have one top animator in the family. Robert McKimson Jr. has three! He is the son of Robert McKimson, one of the greatest animators in history, and the nephew of Tom and Chuck McKimson, also wonderful animators and comic artists. Robert has written a touching tribute to his talented relations and tells us much about their early years and influences, as well as fascinating details about their work that are not generally known.

The style of animation from the 1930s to the 1950s was largely dominated by Walt Disney. The main alternative to Disneys sugary-sweet, sentimental cartoons was Warner Bros., whose loud, brash, and more individual work gave us not only funnier cartoons but also characters that were much more nuanced, specific, and believable.

Bob McKimson

While Disneys personality often overshadowed the contributions of his very talented animators, Warner Bros. allowed varied and unique talents like Tex Avery, Bob Clampett, and Chuck Jones to put their personal stamp on their work. Warners animators and directors developed quirky individual styles that would have been buried at the larger and more homogenized Disney factory. But in the midst of all these personal touches and individual approaches, the studio needed a foundation upon which to build these variations. Bob McKimson was that foundation.

Bob as an Animator

One of my biggest personal heroes, Bob has to be one of the most important figures in animation history. He was the strongest draftsman at Warner Bros. (and maybe even in the whole industry), played the part of teacher in the studio, and was the anchor of the animation department. In the 1930s, the other directors relied on him as head animator to create the most difficult scenes and train the other animators. He did all this while cranking out the most footage of all the animators50 feet a week, which was double the quota!

Bob developed his own unique way of animating that was less bouncy and floppy-looking than the Disney style. His animation was very direct and down to earth, and it was drawn solidly. He set the standard for the quality of Warner Bros. cartoons during the 1930s. The huge talents who became famous later all developed individual variations of Bobs basic style. Ken Harris (The Pink Panther, How the Grinch Stole Christmas) often said how grateful he was to Bob for teaching him to animate.

Bob did animation work for almost all the other directors at some point during the 30sChuck Jones, Tex Avery, Friz Frelengand always turned out solid, impressive stuff. He animated the formative design for Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny in Elmers Candid Camera and A Wild Hare (both released in 1940), setting the pattern for both the series and the studio itself.

I think Bob did his best animation work while in Bob Clampetts unit, from 1941 to 1944. I knew Clampett, and he told me with great reverence that Bob McKimson was his top animator and that he always gave him the most difficult scenes, the ones the other animators would be afraid to do. Clampett had a way of pushing his artists to do things beyond what they thought they could do on their own. He discovered that McKimson not only drew and animated very solidly, but that he had a photographicand, even more astounding, a filmographicmemory.

Directors, including Clampett, usually drew many of the characters poses for their animators and then left it up to the animators to polish the work. In Bobs case, Clampett took advantage of his extra sensory power. Instead of giving him drawings to work with, Clampett acted out the scenes live in front of Bob. This resulted in a more nuanced and realistic sort of animation. As he watched Clampett perform, Bob memorized every little subtle expression and human gesture, then turned around and animated the whole thing perfectly. One example of this remarkable new kind of animation acting is Falling Hare (1943), in which Bugs Bunny sits on the wing of a plane in a relaxed pose and reads a fairy tale about gremlins sabotaging planes.

One of the hardest things to animate is a character moving slowly. Facial features tend to float around the head and detach themselves from the form. But Bob seemed to relish this most difficult task. Add to that the extra impossibility of animating subtle and realistic facial expressions, body language, and hand gestures, as opposed to the floppy, squashy-stretchy style of animation that purposely avoids difficult drawing, and you get a completely new kind of animation, one that Ive only seen in Clampett-McKimson team-ups.

It was this revolutionary kind of animation that largely contributed to Bugs Bunnys personality, and Elmer Fudds, for that matter. Bobs subtle animation of Bugs pretending to die in Elmers arms in A Wild Hare is classic, one of the funniest scenarios in cartoon history, so funny that both Avery and Clampett used it, and always had Bob animate it. I dont know anyone else who could have pulled it off.

Bob is also known for his dynamic and solid posing and wildly exaggerated perspective. He could animate characters leaning toward and away from the camera while still controlling all the dialogue acting and overlapping arm gestures. He animated the best Hitler ever in Clampetts Russian Rhapsody (1944). In the cartoon, Hitler is delivering a typically nutty speech, pounding the podium and leaning forward as he sputters and drools on his audience before rearing ridiculously far back to anticipate the next forward lean. Bob exaggerated the perspective in his acting beyond what you would think is possible and used that technique to great effect later in his Foghorn Leghorn cartoons. Even as a kid, I always looked forward to those scenes and used to imitate them to entertain my friends. I didnt know at the time who had invented them.

Next page