Mishi Saran was born in Allahabad in 1968, but has not lived in India since the age of ten. She graduated with a degree in Chinese studies from Wellesley College, USA, and spent two years in Beijing and Nanjing. In 1994 she moved to Hong Kong, where she worked as a news reporter until she became more interested in travel writing and fiction. She is currently working on her next book.

Authors Note

In AD 627, the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang

At that time Chinese translations of Buddhist texts were garbled and imperfect, particularly those of the Yogacara school, which most interested Xuanzang. Driven by a hunger to know exactly what the texts said, and perhaps also by a sense of adventure, Xuanzang travelled 10,000 miles, and spent about ten years in India. He studied with the great philosopher Silabhadra at Nalanda University in Bihar, and carried 657 sutras back with him.

China was then under the rule of the great emperor Taizong of the Tang dynasty, while much of northern and central India was under the rule of the great king Harshavardhana, who was a patron of Buddhism, although by then Buddhism in India was in decline. Xuanzang notes the many dilapidated and abandoned monasteries he found in the country, in contrast to the accounts of another visiting Chinese monk, Fa Xian, 200 years earlier.

Xuanzangs records of his travels provide an extraordinarily comprehensive account of western China, Central Asia, Afghanistan, the Gandharan regions and India in the seventh century, just before Islam became a dominant influence in some of these areas. On his return to China, Xuanzang set up his own, short-lived, school of Buddhist thought, and his greatest service to Buddhism in China was translating the texts he carried back from India. Many no longer exist in Sanskrit but are preserved in their Chinese translation.

We are lucky to also have a biography of Xuanzang, penned by a contemporary monk, the Shaman Hui Li. It is likely that the two spent much time discussing the travels and, despite his hagiographic bent, Hui Lis accounts are often more vivid than Xuanzangs own records.

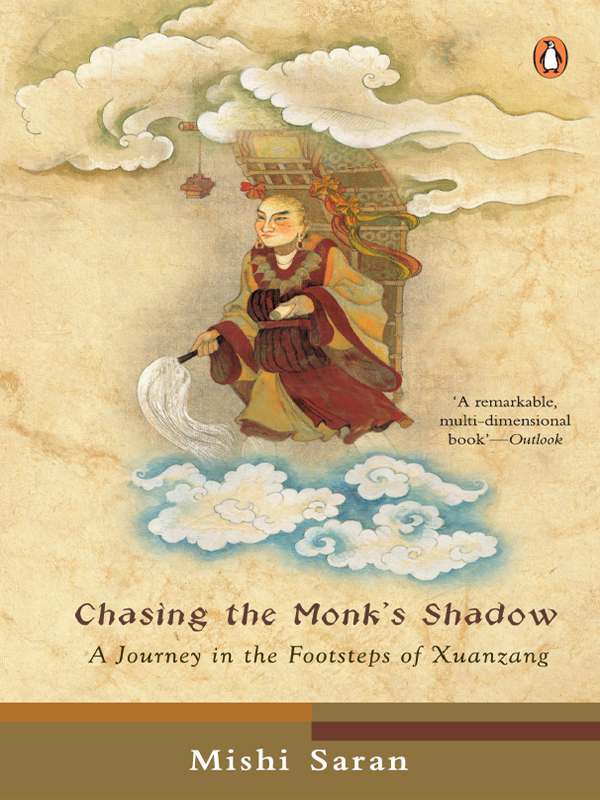

Xuanzangs epic journey has become the stuff of legend in China and has inspired considerable literature. In the sixteenth century, Chinese author Wu Chengen created a splendid mythical journey based on Xuanzangs voyageJourney to the West. Wu added a monkey king with magical powers and threw in demons and battles. The account is so popular that people in China today often confuse the fictional monka rather spineless, trembling creature protected by the heroic monkeyand the real Xuanzang.

To follow the monks route to India, I set off from my home in Hong Kong in May 2000. That summer, I took the train across China and continued overland into Kyrgyzstan. From the capital, Bishkek, I flew to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and then hired a car to take me south to the Afghan border. As it was still closed and I did not have a Pakistan visa, I returned to Tashkent, from where I flew to Delhi to begin retracing Xuanzangs journeys in India. From November to June 2001, I travelled around India by bus, train, car and occasionally by plane. When I finally got my visa to Pakistan in the summer of 2001, I took the bus across the Wagah border to Lahore and travelled through northern Pakistan by road. From there I went to Afghanistan in August 2001, through the Khyber Pass. My journey in Xuanzangs footsteps ended in Kabul, then still under Taliban rule, just a month before 9/11.

Chapter One

The Road to India

AD 600.

AD 600.

One chilly morning deep in a village in China, a woman gave birth as snowflakes fell over fallow fields and the river Chen purled and looped. She sweated and pushed, screamed and cursed under cotton quilts. Her fourth child came with crunched eyes, bunched fists, slippery with blood. She named him Chen Yi. Outside, they say, a phoenix flapped its wings and settled in a tree. It dripped gold light from the tips of its feathers, shuffled along a branch and twittered softly. What is born must suffer and then die, this is the law.

When the time came, Buddhist monks knelt the child on the floor to shave his head, and dark, silky hair fell in piles. They inducted him as a novice and changed his name to Xuanzang.

Before he died, a journey took shape, a tale penned by the fragile light of candles, a brush lifted, a wrist poised for the first stroke of history. The story was one mans truth, about his travels to India in search of scriptures, a journey as he chose to tell it, written in the classical Chinese of the Tang dynasty.

Xuanzangs account was precise. It consisted of directions, the number of days he walked, distances, crops, rivers, kings and customs. He recorded information from the conversations he heard in monastic corridors, from traders roughened by travel and accustomed to risk.

Ta Tang Xi You Ji, Xuanzangs Records of the Western World (written in) the Great Tang Dynasty, was completed in AD 648 by order of the Tang emperor Taizong. The Chinese tome was translated into English by the Reverend Samuel Beal, professor of Chinese at the University College London, and first published in 1884. It was an erudite work in several volumes. It had explanatory footnotes with cross-references to Greek historians and Sanskrit specialists.

So exact had the monk been in his directions, that archaeologists in each of the countries he traversed had used his pointers to fix and then dig up the old cities of the seventh century. As for historians seeking a picture of the Indian subcontinent in medieval times, it was a rare source of information. Between its pages lay the road to India.

I flipped through Xuanzangs records almost 1400 years later, and thought that the written word was a fragile truth. His records were meticulous, but there was a vastness left unsaid. There were spools of thought that fell through the cracks and were swallowed by time. I hungered to know if he ever lost sight of his training, if on empty mountain roads loneliness crept into the sides of his mind till he thought he was mad, if in foreign marketplaces he succumbed to desire or greed or temper.

AD 600.

AD 600.