The

THINGS

THAT

NOBODY

KNOWS

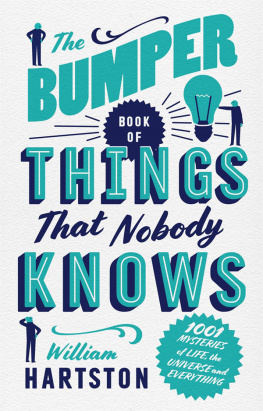

William Hartston is a Cambridge-educated mathematician and industrial psychologist. In his ill-spent youth, he played chess competitively, becoming an international master and winning the British chess championship in 1973 and 1975. He runs a competition in creative thinking for the Mind Sports Olympiad.

He writes the off-beat Beachcomber column for the Daily Express, for which he is also the opera critic, and has written a number of books on chess, numbers, humour, useless academic research and trivia.

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright William Hartston 2011

The moral right of William Hartston to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 184887 825 9

eISBN: 978 085789 716 9

Printed in Great Britain

Design: carrstudio.co.uk

Illustrations Nathan Burton

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

2627 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

How can we remember our ignorance, which our growth requires, when we are using our knowledge all the time?

Henry David Thoreau (181762)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Ignorance, Fruit-Fly Genitalia and the End of the World

There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we now know we dont know. But there are also unknown unknowns. These are things we do not know we dont know.

Donald Rumsfeld, 12 February 2002

The trouble with people like Donald Rumsfeld is that they give ignorance a bad name. The US Secretary of State for Defense was generally derided when he made the clumsy statement quoted above, but he was just trying to remember a line from Confucius quoted by Henry David Thoreau in Walden (1854):

To know that we know what we know, and that we do not know what we do not know, that is true knowledge.

With the wisdom of Confucius supporting him, Thoreau went on to ask:

How can we remember our ignorance, which our growth requires, when we are using our knowledge all the time?

While Rumsfeld was simply categorizing different levels of not knowing, Confucius and Thoreau had a much more positive approach to ignorance, an approach that provides the basic raison dtre of this book. I come to praise ignorance, not to bury it; for there is no better key to understanding the vast and ever-growing expanse of human knowledge. The topics covered in the forthcoming pages are exactly what the book says on the cover: things that nobody knows. Many people, when I have mentioned the title of the book, have unjustifiably assumed it to be another of those not-many-people-know-that collections of useless information. It isnt. There may be a great number of such intriguing facts here, but they are only included when they are crucial to explain what nobody at all knows, and why nobody knows it.

More than three hundred years ago, the French philosopher and mathematician Blaise Pascal likened our knowledge to a sphere which, as it grows larger, inevitably increases the area with which it comes into contact with the unknown. Henry Miller put this more succinctly in The Wisdom of the Heart (1941):

In expanding the field of knowledge we but increase the horizon of ignorance.

This book is a guided tour around Millers horizon of ignorance.

When listening to scientists or other experts talking about the latest advances in their fields, I have always found it more intriguing, and generally more enlightening, when they get on to the subject of the things they dont know. Rumsfelds known unknowns are what determines the direction of future research and that is what makes ignorance so exciting.

According to a recent estimate in the on-line Ulrichsweb periodicals directory, there are around 300,000 academic journals currently being published around the world. These may come out weekly, monthly or less frequently, but the total number of issues of all these journals in any year must be over 3 million, and with an average in the region of ten papers in each journal, each reporting a previously unknown result, that adds up to over 30 million additions to our knowledge every year, which is more than six every second. There has to be a vast amount of ignorance out there to keep all those journals in material, and the things that nobody knows that I have identified in the pages that follow only scratch the surface.

I ought now to write something about ontology, epistemology, Karl Poppers concept of falsifiability, Thomas Kuhns paradigm shifts and everything else that contributes to our ideas of reality, knowledge and what is knowable, but there will be plenty of time for that sort of thing later when we get on to the subject of philosophical unknowns. There is, however, just one more subject that I want to mention: fruit-fly penises.

Male fruit flies have tiny hooks and spines on their penises, the function of which until recently nobody knew. The standard way to resolve such a question would be to shave these bristles off and see what effect this had on the sex life of the subject. In the case of fruit-fly penises, however, the bristles are so small they can only be seen under a microscope, and even the best scalpel is too clumsy an instrument to attempt to use as a razor. At the end of 2009, however, researchers at the University of California published a paper describing a method of shaving fruit-fly penises with a laser. Not only could they shave off the bristles, but they could even perform the task with such accuracy that only the top third of each bristle was trimmed. By comparing the sexual exploits of unshaven, partially shaven, and totally shaven fruit flies, they could then tell everyone what they wanted to know. Answer: the sole role of the hooks and spines is to act as biological Velcro and keep the male fruit fly attached to the female during sex.

And until the paper was published, that is probably something that even Donald Rumsfeld did not know that he did not know.

After toying with various ways of organizing the material, I finally decided to settle for the most systematically arbitrary of all: alphabetical order by subject. Where appropriate, I have included cross-references to related topics at the end of the subject sections. These are introduced by the words see also, followed by the name(s) of the related subject or subjects and the numbers of the relevant unknowns. There are also cross-references embedded within the body of the entries, directing the reader to other entries that shed further light on the topic under scrutiny.

Next page