Four sons of Vernon Dahmer (from left) U.S. Army Sgt. George W. Dahmer, U.S. Air Force Staff Sgt. Martinez A. Dahmer, U.S. Air Force Master Sgt. Vernon F. Dahmer Jr., and U.S. Army Specialist 4th Class Alvin H. Dahmer, called from military service to attend his funeral, inspecting the ruins of his home. (P HOTOGRAPH BY C HRIS M CNAIR )

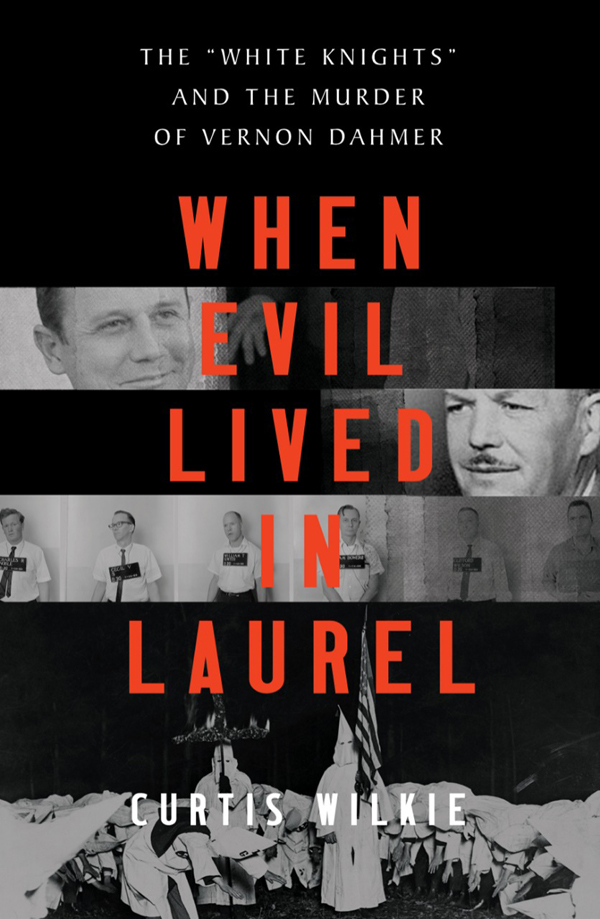

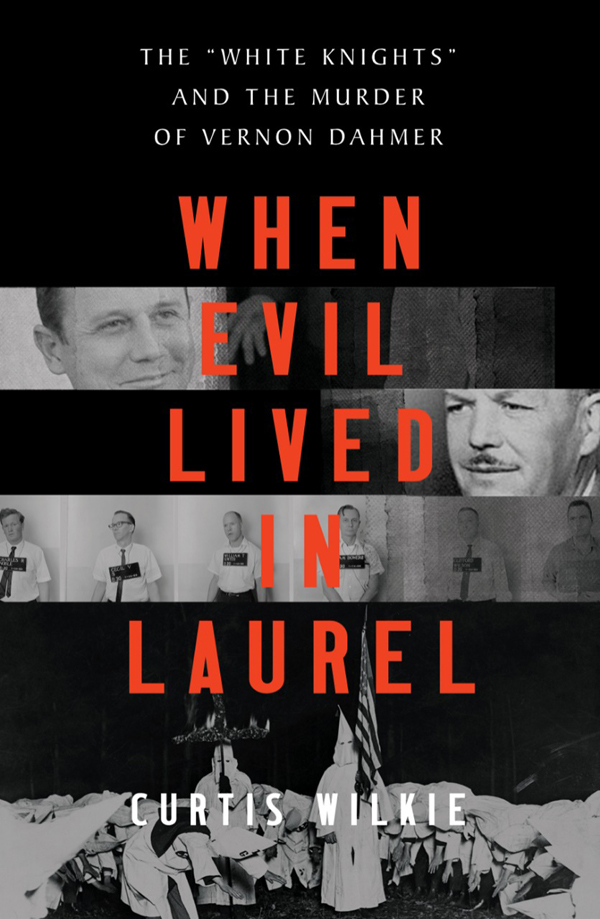

CURTIS WILKIE

WHEN EVIL LIVED IN LAUREL

The White Knights and the Murder of Vernon Dahmer

For Mimi

The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.

attributed to EDMUND BURKE

Authors Note

The quotations in this book come from several different sources. In many cases, verbatim quotes come directly from Tom Landrums reports and other documents, such as FBI interviews, transcripts of testimony in trials, depositions, and records of congressional hearings. Some direct quotes were found in newspapers and periodicals published during the time when the White Knights were active, while others were taken from books. Specific attributions are in the endnotes.

Many of Landrums conversations were reconstructed by me based on interviews with him and his wife, Anne.

In other cases, I re-created dialogue. In every instance, I relied on available information about specific activities and personal encounters to keep these quotes in the spirit of the actual exchanges among these men.

I realize some of the language may be offensive. The Klansmen were generally rough characters; most of them used racial epithets and profanity freely. There is no good way to sugarcoat their behavior. In the interest of reality I preserved their crude and ugly words.

WHEN EVIL LIVED IN LAUREL

Prologue

M AY 8, 1951. Tom Landrum would remember the night and its grim details for the rest of his life. While the humid evening held the prospect of another searing summer, a carnival atmosphere gripped his hometown of Laurel, Mississippi. More than a thousand people had gathered near the Jones County courthouse to await the execution of Willie McGee, a thirty-five-year-old Black man whose case had become a worldwide cause clbre. McGee had been charged with raping a white woman six years earlier. The truck driver insisted the affair had been consensual, but he was convicted and sentenced to death in 1945 shortly after the woman filed a complaint. The verdict was overturned by a higher court; so was a second decision, following a trial where another all-white jury took only eleven minutes to find him guilty. After a third conviction, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to intervene, even as an international clamor grew over this latest example of Mississippi justice. If a Black man was accused of violating a white woman, it called for the supreme penalty. Even if there was doubt about his guilt.

Scores of other Black defendants had been sent to death row on dubious charges in Mississippi and attracted little notice. Unlike those cases, McGees impending doom attracted countless sympathizers, including Albert Einstein, the Mississippi novelist William Faulkner, and the acclaimed singer-actor Paul Robeson. Demonstrators took to the streets on McGees behalf from London to the lawn of the White House. At the Lincoln Memorial, protestors wearing Free Willie McGee T-shirts chained themselves to pillars near the stone image of the Great Emancipator.

Yet the out-of-state activity had little impact in Mississippi, in part because McGee had been represented during his appeal by firebrand New York attorney Bella Abzug, a dedicated leftist whose arguments questioned Mississippi values. Since his defense was financed by the Civil Rights Congress, Mississippians were quick to link the group to the Communist Party and the far left. Support for McGee by thousands of union members outside the South did little good in a region historically hostile to organized labor.

The outcry by those foreign to Jones County only solidified belief in Mississippi that McGee should be put to deathlegally, yet without more delay. Earlier, National Guard units had to be deployed to prevent his lynching between trials. Now, to ensure that McGees death would be carried out properly, preparations had been made to bring the states portable electric chaira device known as Old Sparkyto Laurel and install it in the same courtroom where McGee had been convicted. To ensure adequate voltage, a cable attached to an outside generator was strung through a courthouse window and connected to the electric chair.

With the climax of the long drama at hand, excitement coursed through the town. As the midnight hour for McGees death approached, a local radio station carried live reports for those who had not come to the courthouse. An announcer commented that an execution was not necessarily a joyful occasion, but he added, When it becomes necessary, it must be done. On the streets surrounding the scene, knots of white people waited, some in lawn chairs as if for a picnic. More youthful spectators climbed into trees to get unobstructed views of the courthouse. When a state highway patrolman announced that the time had come for McGee to die, the news provoked cheers. Inside the courtroom, one hundred privileged witnesses had been allowed to see the execution; hundreds of others surrounded the grounds of the courthouse. They knew the procedure had begun when the generator groaned loudly; some imagined that lights dimmed, as happened in such scenes in the movies. The crowd clapped enthusiastically and shouted. They cheered again, a few minutes later, when McGees lifeless body, covered with a white sheet, was loaded onto the hearse of a funeral home serving Black residents of Laurel.

T OM L ANDRUM , a high school senior dressed in working-class denims, watched on the streets of Laurel that night, drawn with his schoolmates to the spectacle. An offspring of one of Jones Countys largest and best-known families, the boy followed the proceedings from a vantage point outside a downtown theater. Some of his friends were among those clinging to high branches of trees. At first Tom was caught up in the excitement over an event that was winning worldwide attention. But when the exercise ended, he recognized the enormity of the activity. It resulted in the death of a man, scorned by the community and condemned to a final, proverbial last supper. The boy was suddenly gripped by the poignancy of the moment; he felt sickened and personally diminished. He said to himself: I should never have come. And he vowed: I will never do something like this again.

CHAPTER 1

M ORE THAN A DECADE LATER , racial antagonism still burned in Jones County, a south Mississippi setting with a complex history. Though the region had earned curious celebrity during the Civil War for a revolt against the Confederacy by a short-lived Free State of Jones, few of those liberal spirits survived. The countys white population was hard-core conservative, reflecting the fundamentalist religious beliefs that prevailed there. Laurel, one of two county seats, was not established until twenty years after the national conflict over slavery had ended and thus could claim none of the nobility attributed to the Old South. No antebellum mansions or stately cypress and oaks dripping with silver threads of Spanish moss graced its streets, as in New Orleans, which lay 150 miles to the south. Instead, Laurel grew up as a small, rough-natured city named for a toxic native bush but nurtured by a timber industry fed by dense surrounding pine forests. Because Jones County often displayed its violent passions in public, few were surprised when in 1964 it became the headquarters for a new and virulent organization known as the White Knights of the Mississippi Ku Klux Klan. The ranks of the local group were mostly made up of resentful men who worked the small farms, oil fields, or logging camps or held jobs on the line at Masonite, a monstrous factory that loomed over the landscape like a brutal force, converting waste wood into fiberboard.

Next page