Contents

Guide

Contents

Foreword

Stefi Orazi

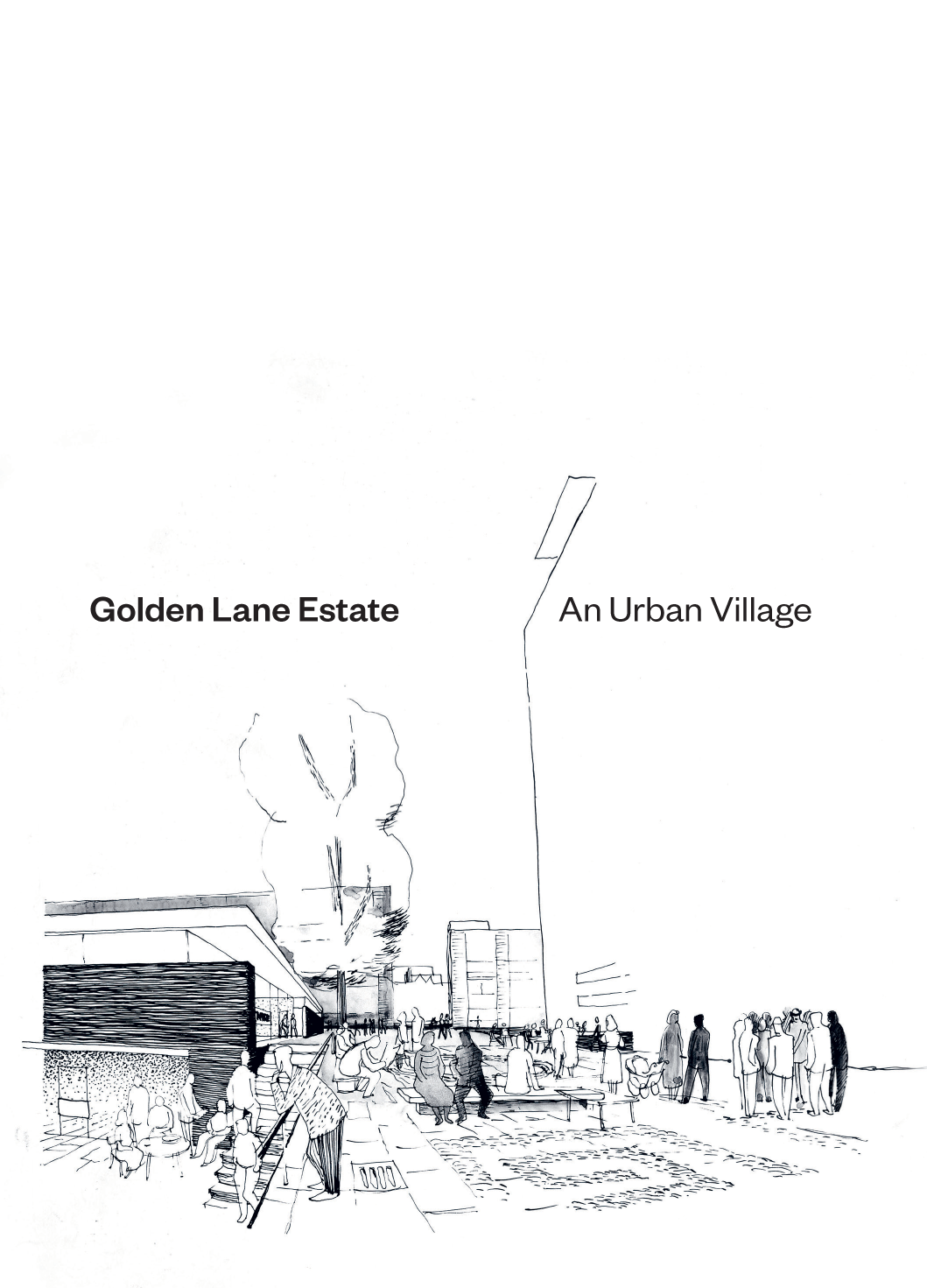

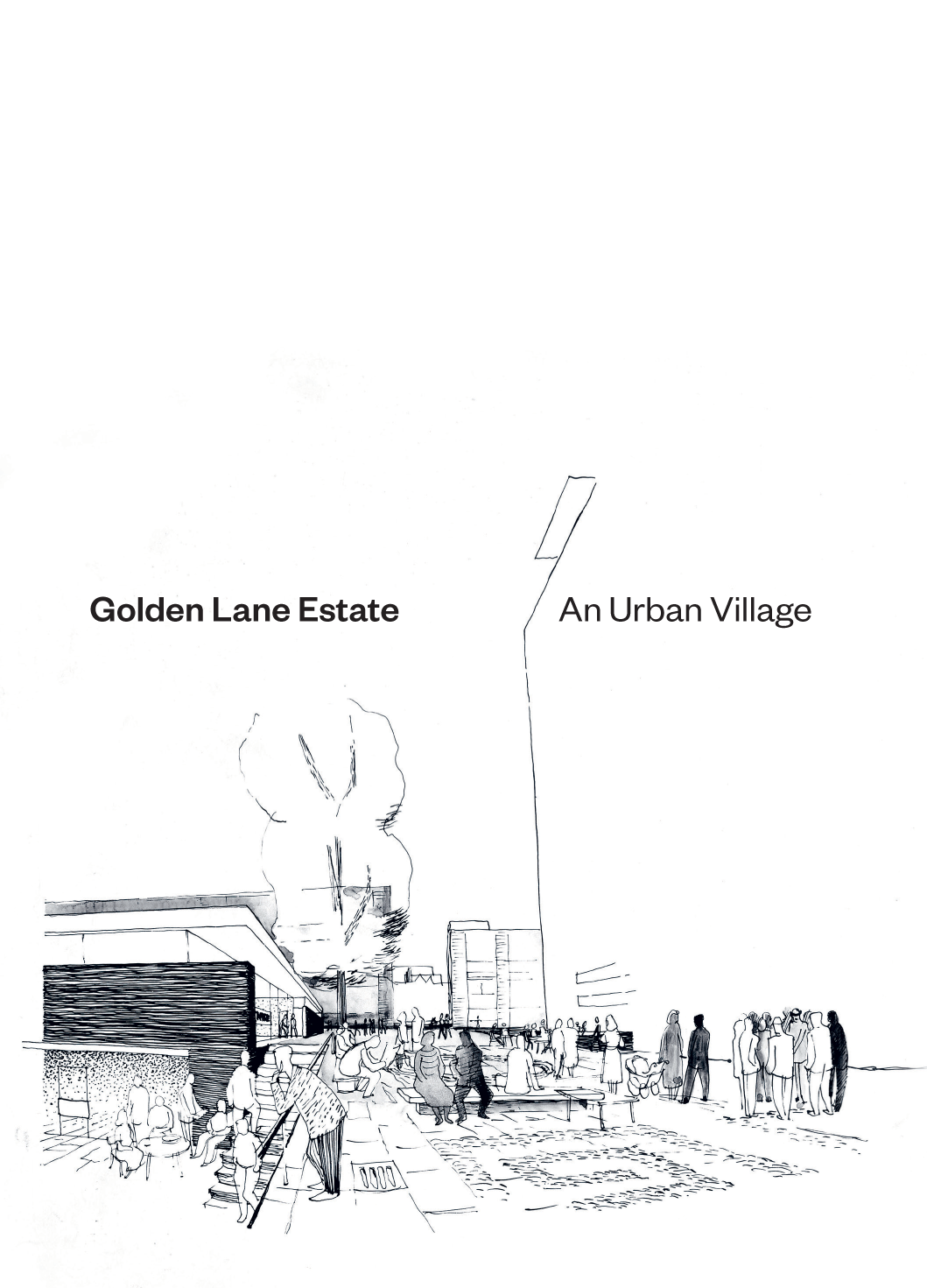

A month before my 30th birthday, I moved into the Golden Lane Estate with my then partner. It was our first home together. After the initial realization of how much renovation the flat needed, we soon became obsessed with its idiosyncratic details: a three-quarter-height partition wall with uplighters integrated into the top; built-in wardrobes with more drawers than anyone with a sock fetish could dream of; a little two-way cupboard next to the front door for milk deliveries; unique cast aluminium door numbers; huge full-width timber windows that pivoted in the centre for easy cleaning the list goes on. Every detail had been thoroughly considered, and as a whole, made the flat utterly charming.

We soon got ourselves involved in the residents association. It was at a time when there was an influx of young creatives moving onto the estate, and the long-standing residents association embraced this new younger generation and, in fact, wanted to attract more of us to join. I volunteered to become the associations graphic designer and produced leaflets and posters to encourage new members. Through this process, I met lots of the residents and many have become life-long friends.

I lived on the estate for nearly ten years, and in three different types of flats, each unique in character, and in each the hand of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon could be felt. It is this relationship with the architecture and its architects that makes the estate feel so personal, and my attachment to it, as with many residents, is an emotional one. It was, therefore, with a degree of reservation that when I was approached by Batsford to create this book, I agreed to take it on. During the time I lived there, I saw a decline in the maintenance of the buildings. The once regular cyclical works programme seemed to have been abandoned, the promise of new windows across the estate was regularly shelved and delayed. Residents had begun to become increasingly frustrated and their voices not listened to. I knew that interviewing residents for this book would not be an easy listen (its worth mentioning that my request to interview the estate management for this project was declined). Of course, this is not a problem unique to Golden Lane: any estate, particularly one that is coming up to 70 years old and is Grade II and Grade II* listed, faces the challenge of how to bring it up to 21st-century standards, especially within the constraints of a limited budget. In many ways, it has fared better than other council estates due to the quality of its design and wealthy central London location, and it has not faced the antisocial behaviour some estates have.

Many of the original residents have sadly passed away since I first moved there, and this is a very different book to one that would have been made a decade ago. The sense of community, however, is still very strong and like nowhere else I have experienced before or since. With the successful refurbishment of the community centre a few years ago, and the recladding of the Great Arthur House tower recently, the estate has been given a new lease of life. With firm plans for an estate-wide upgrade of the windows now in place, I hope that Golden Lane is now given the attention it deserves, and that the City of London seeks the knowledge of the people who know and care for it most its residents.

Childrens paddling pool (now turfed over), views south towards Cullum Welch House and Great Arthur House beyond, 1964

Introduction

Elain Harwood

The History of the Golden Lane Estate

Golden Lane, running north from the City of Londons boundary, was first developed in the thirteenth century. The dominant feature by the late sixteenth century was a brewery, which stood amid small houses and shops roughly on the site of Stanley Cohen House and the lawn behind it () suggests that Golden Lane had similarities with present-day Whitecross Street, which runs parallel to the east. To the west, behind the brewery, there lay a jumble of short residential terraces between the slightly grander Bridgewater Square to the south and the more orderly Hatfield Street to the north. To meet the demand of the expanding city, lots of local builders had developed tiny plots of land, leaving open space between them and creating a singularly haphazard, incoherent maze of culs-de-sac and alleyways.

The open spaces did not last long. As the breweries fell into the hands of a few large companies from the mid-nineteenth century onwards and their number was rationalized, so the area became the centre of Londons rag trade, with showrooms, warehouses and factories. The Builder magazine in March 1879 reported that Golden Lane was about to be doubled in width on its west side and rebuilt with large warehouses and business premises, following a similar operation nearing completion along Fann Street. The rest of the site became a dumping ground for rubble cleared from the surrounding streets.

The Golden Lane Competition

The City of London boundary cut across Golden Lane, and so the site off Fann Street was subject to the strictures of both the London County Council (LCC), as overall planning authority, and the City of London Corporation. The County of London Plan produced by J H Forshaw and Patrick Abercrombie for the LCC in 1943 proposed a continued business use for the area, as in 1944 did the Corporations City of London Plan, the work of the chief engineer, Francis J Forty. In practice, however, the Second World War hastened the westward migration of the fashion wholesalers and showrooms to the area north of Oxford Street, which had already begun in the 1930s. The LCC and Royal Fine Art Commission criticized Fortys plan as too conservative with its limited proposals for new roads and more open space, and in response the City brought in two well-respected architects, Charles Holden and William Holford, to make revisions.

Aerial view of the Genuine Beer Brewery, Golden Lane, 1807

Map of London (detail) by R.ichard Horwood, 1795

The City of London Corporations Public Health Committee turned its eyes towards cheaper land on the boundary with the working-class borough of Finsbury. Its chairman, Eric F Wilkins, was drawn to the derelict site off Golden Lane, where Finsbury Borough Council was slowly removing the rubble at the rate of 7,000 cubic yards (5,300 cubic metres) per month; such was the height of the mound that he estimated that it would take three years to clear.

The first major housing competition since that held by Westminster City Council for Churchill Gardens in 1945, Golden Lane attracted 178 entries from across Britain, many by young architects. They were exhibited for a week in March 1952 at Londons Guildhall. The Public Health Committee reported that a large majority of the entries reach a high standard of design, many being valuable contributions to the study of urban housing.