Porch - The conquest of Morocco

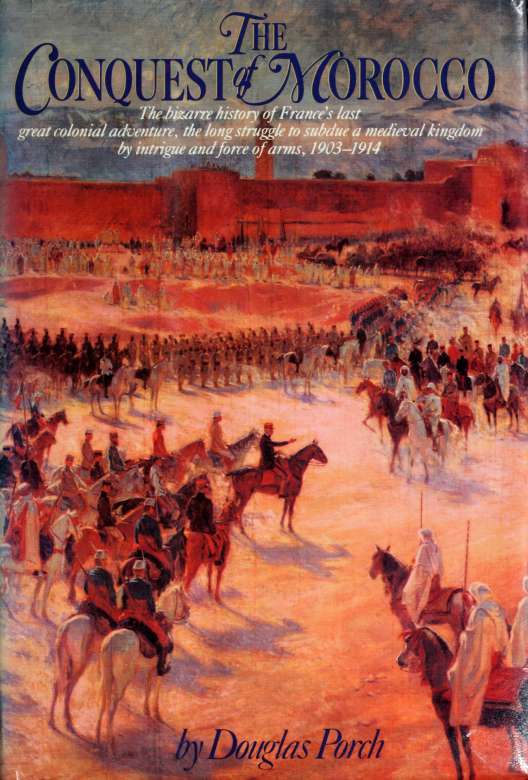

Here you can read online Porch - The conquest of Morocco full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1983, publisher: New York : Knopf, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The conquest of Morocco

- Author:

- Publisher:New York : Knopf

- Genre:

- Year:1983

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The conquest of Morocco: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The conquest of Morocco" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The conquest of Morocco — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The conquest of Morocco" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This book made available by the Internet Archive.

FOR CHARLES

Contents

XV THE FIRST SIEGE OF FEZ 213

XVI THE RESCUE 223

XVII THE MASSACRE 256

XVIII THE SECOND SIEGE OF FEZ 248

XIX MARRAKECH 2^8

XX THEZAER 27/

XXI CONSOLIDATION AND DEFEAT 279

Epilogue 289

Notes 2gg

Selected Bibliography ?; ^

PREFACE >

The origins of this book lie in my interest in the French Army and, more specifically, a faction of itthe French Army in the colonies. In our own era, when so much of the world's disorder since 1945 in Algeria, black Africa, Afghanistan and the dreadful and tragic conflict which still continues in Indochinahas assumed the shape of the "war of the flea," a book that attempts to explain the origins of colonialism and the methods of its conquests may be relevant.

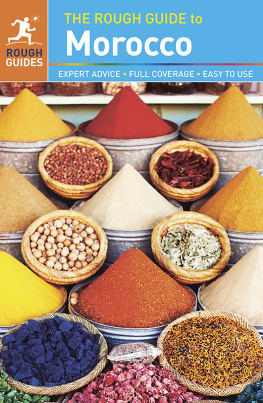

But history is not about parallels. It tells its own story, and that of the conquest of Morocco by France is a particularly compelling one. Morocco is a beautiful country and, in the early years of this century, it was still a wild and primitive one. Europeans were simultaneously drawn to Morocco and repelled by it, charmed by its savagery and, at the same time, the conscious if sometimes reluctant agents of its "civilization." The story of the conquest is that of the meeting of two cultures. Islamic and Christian. It is also about what contemporaries saw as the meeting of the modern age and the medieval world, of two peoples so distinct in mental, moral and physical condition as to belong not only to different continents but to separate historical epochs. I have attempted, through the use of documents and memoirs of the period, to convey something of the shock of that meeting. Where possible, I have offered the Moroccan point of view. But the documentary evidence is overwhelmingly European.

The French took ninety years to absorb Morocco, from the Battle of Isly in 1844 to the final submission of the Tafilalet in 1934. However, I have concentrated on the decade or so before the outbreak of the Great War. This offers a more manageable period, and one that includes the major events of the conquest. Before Lyautey's arrival in the South Oranais in 1903, the French advance had been spasmodic and unsustained. After 1914, when France proved that she could hold both on the Marne and in Morocco, all that remained to be accomplished, the Rif War apart, was to clean up a few pockets of "dissidence" in the mountains.

The actors in the drama were extraordinary people. The forty-three

Preface

years of peace that began with the Treaty of Frankfurt in 1871 and ended abruptly in August 1914 appear in retrospect to be the last heroic age. This perhaps explains, at least in part, our current nostalgia for the world of Victoria and Edward. If our moral certainties appear to have disintegrated before forces too complex to understand, much less to counter, it is refreshing to step back into an era that appeared convinced of its values and confident of its future. It was this confidence in themselves and in their world that sustained the great figures of pre-1914 Europe, and that made subsequent generations of leaders, deprived of any basic set of beliefs in a world fragmented by war, economic chaos and political confusion, appear hesitant, shallow and opportunistic by comparison.

No one aspect of this period of European history was more obviously heroic than the exploration and conquest of Africa. The movement which made Livingstone and Stanley, Gordon and Kitchener, Marchand and Lyautey, household names has been regarded as the prime expression of the age. The more I study this period, however, the more I am convinced that colonial expansion, at least for the men who carried it out, was a countermovement, antiprogressive, a rejection of the age rather than an expression of it. Despite the talk of filling in the blank spaces on the map, of civilizing the natives, of providing markets and raw materials for European industry, Africa in fact offered an escape from a Europe in which technology was already allocating to everyone their minor tasks in an increasingly complex economic and social structure. Post-1871 Europe was changing rapidly. Men of strong religious conviction like Livingstone and Gordon, dissatisfied in a society devoted almost exclusively to increasing its material comfort, or, like Marchand, Lyautey, or any number of colonial soldiers, unhappy with the functionary's role assigned to them at home, sought asylum in Africa. "Renown," said Tacitus, "is easier won among perils." The explorers and conquerors of Africa were not so much thrown up by an expanding Europe as thrown out by it. Africa became a catchbag for European misfits, lionized abroad, unhappy and out of place at home.

Of no one was this more true than Hubert Lyautey. For the man whom Lloyd George called "the prince of proconsuls," whose name is indelibly linked with the conquest of Morocco, no good biography exists. Why has Francewhich cherishes her great men as servants of her civilization deliberately chosen to ignore one of her greatest sons? The answer probably lies both in Lyautey's character and in the relationship of France with her

Preface

colonies. Lyautey was both an eccentric and a colonial. While both characteristics earned for him, despite his rabid Anglophobia, a place in British esteem, in France they conspired to deflate his claims as a serious subject for biography. Colorful eccentricity has never enjoyed the acceptance in France which it can expect in Britain. But Frenchmen feel uncomfortable with Lyautey for reasons other than those connected with his personality. His ideas and politics cannot be slotted into a recognizable modern intellectual pattern, as can those even of other archreactionaries like Charles Maurras. Lyautey stands out as a loner, an individualist, a magnificent anachronism, a man with admirers perhaps but with no disciples. For French scholars, Lyautey is an isolated phenomenon, an intellectual cul-de-sac, a mere spectator who stands apart from the mainstream of French cultural life.

None of Lyautey's ideas was less fashionable, even in his own lifetime, than colonialism. While the empire was a source of pride in Britain, Frenchmen were at best ambivalent about the acres of desert, scrub and jungle brought under the flag by ambitious soldiers. The brutal methods of the colonizers frequently proved a source of scandal. While no particular opprobrium is attached to Lyautey's name, his association with an enterprise regarded by many in his country, then as now, as shameful is in part responsible for his being largely passed over by historians. Perhaps, too, the Marxist bias of much of French academic history, which tends to denigrate the influence of personality in favor of impersonal economic forces, has worked against Lyautey: why blow the penny whistle when one can summon up le grand orchestre'!

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The conquest of Morocco»

Look at similar books to The conquest of Morocco. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The conquest of Morocco and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.