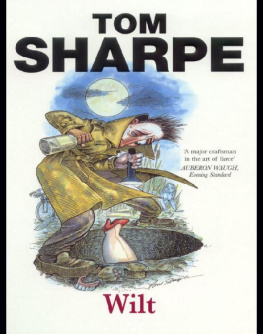

Tom Sharpe - Wilt

Here you can read online Tom Sharpe - Wilt full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1999, publisher: Overlook TP, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Wilt

- Author:

- Publisher:Overlook TP

- Genre:

- Year:1999

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wilt: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wilt" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wilt — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Wilt" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Whenever Henry Wilt took the dog for a walk, or, to be more accurate, when the dog took him, or, to be exact, when Mrs Wilt told them both to go and take themselves out of the house so that she could do her yoga exercises, he always took the same route. In fact the dog followed the route and Wilt followed the dog. They went down past the Post Office, across the playground, under the railway bridge and out on to the footpath by the river. A mile along the river and then under the railway line again and back through streets where the houses were bigger than Wilts semi and where there were large trees and gardens and the cars were all Rovers and Mercedes. It was here that Clem, a pedigree Labrador, evidently feeling more at home, did his business while Wilt stood looking around rather uneasily, conscious that this was not his sort of neighbourhood and wishing it was. It was about the only time during their walk that he was at all aware of his surroundings. For the rest of the way Wilts walk was an interior one and followed an itinerary completely at variance with his own appearance and that of his route. It was in fact a journey of wishful thinking, a pilgrimage along trails of remote possibility involving the irrevocable disappearance of Mrs Wilt, the sudden acquisition of wealth, power, what he would do if he was appointed Minister of Education or, better still, Prime Minister. It was partly concocted of a series of desperate expedients and partly in an unspoken dialogue so that anyone noticing Wilt (and most people didnt) might have seen his lips move occasionally and his mouth curl into what he fondly imagined was a sardonic smile as he dealt with questions or parried arguments with devastating repartee. It was on one of these walks taken in the rain after a particularly trying day at the Tech that Wilt first conceived the notion that he would only be able to fulfil his latent promise and call his life his own if some not entirely fortuitous disaster overtook his wife.

Like everything else in Henry Wilts life it was not a sudden decision. He was not a decisive man. Ten years as an Assistant Lecturer (Grade Two) at the Fenland College of Arts and Technology was proof of that. For ten years he had remained in the Liberal Studies Department teaching classes of Gasfitters, Plasterers, Bricklayers and Plumbers. Or keeping them quiet. And for ten long years he had spent his days going from classroom to classroom with two dozen copies of Sons and Lovers or Orwells Essays or Candide or The Lord of the Flies and had done his damnedest to extend the sensibilities of Day-Release Apprentices with notable lack of success.

Exposure to Culture, Mr Morris, the Head of Liberal Studies, called it but from Wilts point of view it looked more like his own exposure to barbarism, and certainly the experience had undermined the ideals and illusions which had sustained him in his younger days. So had twelve years of marriage to Eva.

If Gasfitters could go through life wholly impervious to the emotional significance of the interpersonal relationships portrayed in Sons and Lovers, and coarsely amused by D.H. Lawrences profound insight into the sexual nature of existence, Eva Wilt was incapable of such detachment. She hurled herself into cultural activities and self-improvement with an enthusiasm that tormented Wilt. Worse still, her notion of culture varied from week to week, sometimes embracing Barbara Cartland and Anya Seton, sometimes Ouspensky, sometimes Kenneth Clark, but more often the instructor at the Pottery Class on Tuesdays or the lecturer on Transcendental Meditation on Thursdays, so that Wilt never knew what he was coming home to except a hastily cooked supper, some forcibly expressed opinions about his lack of ambition, and a half-baked intellectual eclecticism that left him disoriented.

To escape from the memory of Gasfitters as putative human beings and of Eva in the lotus position, Wilt walked by the river thinking dark thoughts, made darker still by the knowledge that for the fifth year running his application to be promoted to Senior Lecturer was almost certain to be turned down and that unless he did something soon he would be doomed to Gasfitters Three and Plasterers Two and to Eva for the rest of his life. It was not a prospect to be borne. He would act decisively. Above his head a train thundered by. Wilt stood watching its dwindling lights and thought about accidents involving level crossings.

Hes in such a funny state these days, said Eva Wilt, I dont know what to make of him.

Ive given up trying with Patrick, said Mavis Mottram studying Evas vase critically. I think Ill put the lupin just a fraction of an inch to the left. Then it will help to emphasise the oratorical qualities of the rose. Now the iris over here. One must try to achieve an almost audible effect of contrasting colours. Contrapuntal, one might say.

Eva nodded and sighed. He used to be so energetic, she said, but now he just sits about the house watching telly. Its as much as I can do to get him to take the dog for a walk.

He probably misses the children, said Mavis. I know Patrick does.

Thats because he has some to miss, said Eva Wilt bitterly. Henry cant even whip up the energy to have any

Im so sorry, Eva. I forgot, said Mavis, adjusting the lupin so that it clashed more significantly with a geranium.

Theres no need to be sorry, said Eva, who didnt number self-pity among her failings, I suppose I should be grateful. I mean, imagine having children like Henry. Hes so uncreative, and besides children are so tiresome. They take up all ones creative energy.

Mavis Mottram moved away to help someone else to achieve a contrapuntal effect, this time with nasturtiums and hollyhocks in a cerise bowl. Eva fiddled with her rose. Mavis was so lucky. She had Patrick, and Patrick Mottram was such an energetic man. Eva, in spite of her size, placed great-emphasis on energy, energy and creativity, so that even quite sensible people who were not unduly impressionable found themselves exhausted after ten minutes in her company. In the lotus position at her yoga class she managed to exude energy, and her attempts at Transcendental Meditation had been likened to a pressure-cooker on simmer. And with creative energy there came enthusiasm, the febrile enthusiasms of the evidently unfulfilled woman for whom each new idea heralds the dawn of a new day and vice versa. Since the ideas she espoused were either trite or incomprehensible to her, her attachment to them was correspondingly brief and did nothing to fill the gap left in her life by Henry Wilts lack of attainment. While he lived a violent life in his imagination, Eva, lacking any imagination at all, lived violently in fact. She threw herself into things, situations, new friends, groups and happenings with a reckless abandon that concealed the fact that she lacked the emotional stamina to stay for more than a moment. Now, as she backed away from her vase, she bumped into someone behind her.

I beg your pardon, she said and turned to find herself looking into a pair of dark eyes.

No need to apologise, said the woman in an American accent. She was slight and dressed with a simple scruffiness that was beyond Eva Wilts moderate income.

Im Eva Wilt, said Eva, who had once attended a class on Getting to Know People at the Oakrington Village College. My husband lectures at the Tech and we live at 34 Parkview Avenue.

Sally Pringsheim, said the woman with a smile. Were in Rossiter Grove. Were over on a sabbatical. Gaskells a biochemist.

Eva Wilt accepted the distinctions and congratulated herself on her perspicacity about the blue jeans and the sweater. People who lived in Rossiter Grove were a cut above Parkview Avenue and husbands who were biochemists on sabbatical were also in the University. Eva Wilts world was made up of such nuances.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Wilt»

Look at similar books to Wilt. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Wilt and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.