PENGUIN BOOKS

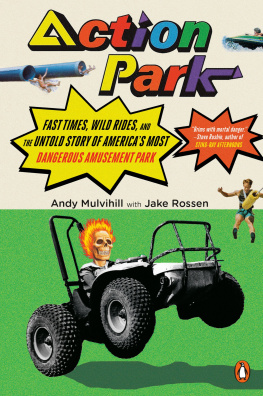

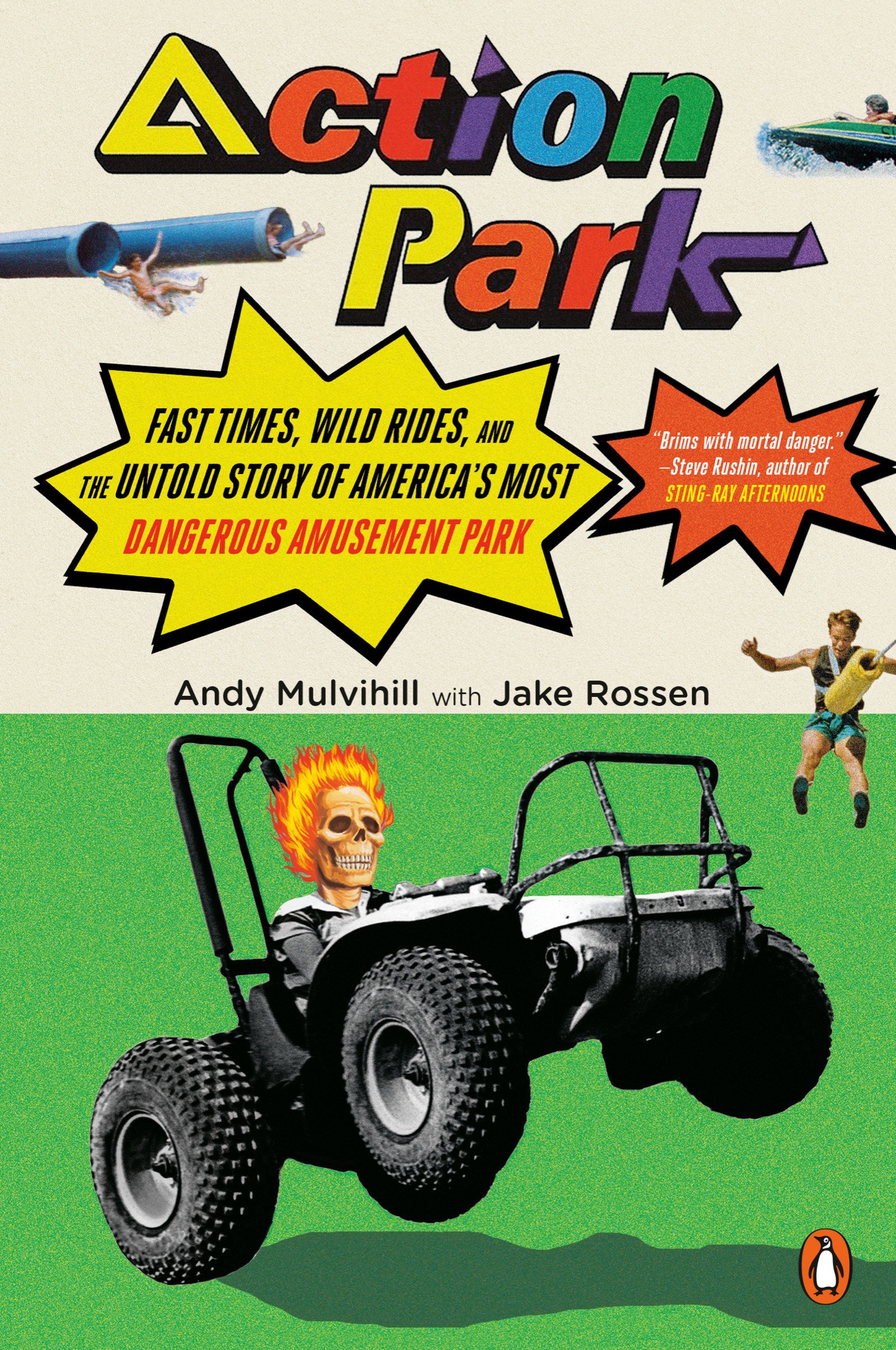

ACTION PARK

Andy Mulvihill is the son of Action Park founder Gene Mulvihill. At the park, Andy worked testing rides and as a lifeguard before moving into a managerial role. He is currently the CEO of Crystal Springs Resort Real Estate.

Jake Rossen is a senior staff writer at Mental Floss. His byline has appeared in The New York Times,Playboy, The Village Voice, ESPN.com, and Maxim, among other outlets. He is also the author of Superman vs. Hollywood, which examines the life of the Man of Steel from 1940s radio dramas to big-budget features.

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2020 by Andrew J. Mulvihill

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

All photos courtesy of the author.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Mulvihill, Andy, author. | Rossen, Jake, author.

Title: Action Park : fast times, wild rides, and the untold story of Americas most dangerous amusement park / Andy Mulvihill with Jake Rossen.

Description: New York : Penguin Books, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020011878 (print) | LCCN 2020011879 (ebook) | ISBN 9780143134510 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9780525506294 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Action Park (Vernon, N.J.)History. | New JerseySocial life and customs20th century.

Classification: LCC GV1853.3.N52 A476 2020 (print) | LCC GV1853.3.N52 (ebook) | DDC 791.06/874976dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020011878

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020011879

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Cover design: Alex Merto

Cover images: courtesy of the author

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

For Gene

Contents

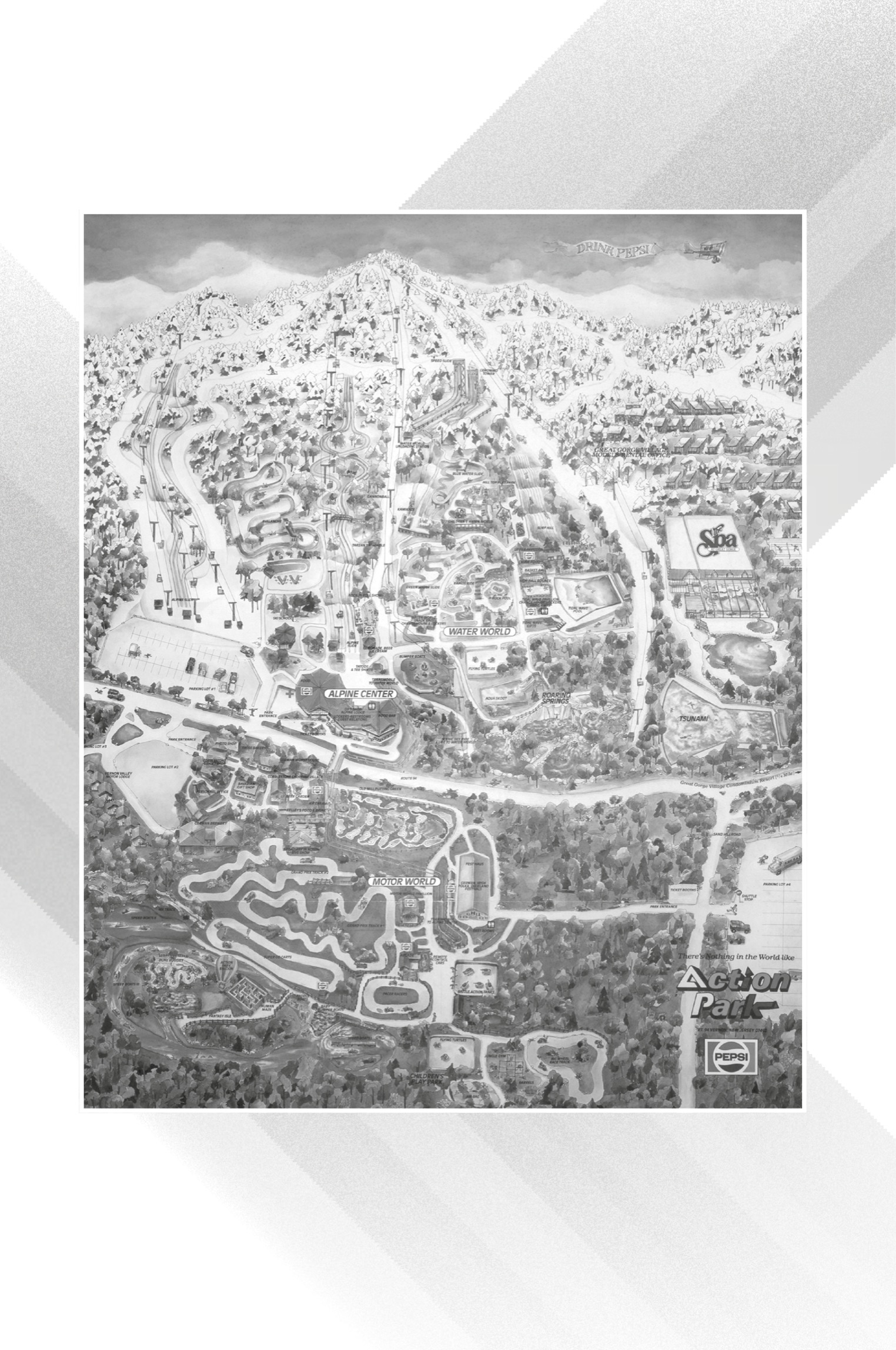

The Cannonball Loop, open only sporadically over the years due to its uncanny ability to maim our guests.

PROLOGUE

My knees will not stop trembling.

Im standing some sixty feet in the air at the mouth of an enclosed water slide, padded hockey equipment cinched tightly to my arms, legs, and torso. The artificial bulk is intended to protect my adolescent body against whatever trauma is waiting at the other end. Leaning precariously against a dirt-strewn hill in an empty parking lot, the blue tube resembles a giant drinking straw with a knot inexplicably tied at the bottom.

The hope is that, if I jump in, my momentum will push me through the improbable three-hundred-and-sixty degree vertical turn at the far end and out the other side. It feels like the kind of thing NASA would force astronauts to do to assess their fitness for space. I envision a doctor using a penlight to look at my unfocused pupils in the aftermath, offering a dismissive shake of his head at my poor judgment.

As he wraps my head in bandages, I will tell him it was not my idea. It was my fathers.

According to my older sister, Julie, Im the first human to make the attempt. Prior to this, someone had tied off the ankles and sleeves of an old janitorial jumpsuit, stuffed it with sand, and fabricated a head out of a plastic grocery bag. The makeshift dummy cleared the loop but emerged decapitated.

We havent told Mom youre doing this, she says, by way of encouragement.

Today, a mechanical engineer would use computer software to calculate the exact pitch of the chute required for riders to make it through successfully. An army of lawyers would pour over the injury statistics for comparable attractions and demand changes based on risk mitigation. A feasibility expert would evaluate plans and anticipate logistical issues.

This being 1980, none of that happened. Instead, my father drew the slide on a cocktail napkin and hired some local welders, who had just been laid off from a nearby car factory, to cobble it together. On windy days, it wobbles back and forth, perilously unanchored to its temporary location in the lot.

Looks feasible, he said.

I peer into the opening. The smell of the industrial glue that adheres the foam to the tubing stings my nostrils. (Later, the fumes from this same glue, combined with a lack of ventilation, will cause workers erecting other rides to pass out, angering my father with their reduced productivity.) Its so completely and utterly dark inside that jumping in seems like attempting interdimensional travel. Ive tested rides for my fathers amusement park before, and teenage bravado has always trumped common sense, but this thinghe calls it the Cannonball Loopis giving me second thoughts.

Im sixteen years old and about to become the Chuck Yeager of this monument to the total perversion of physics.

Andy!

I look down at my father. Hes tall, about six-two, with a booming voice that adds a few inches. His hair, neatly combed, gives him the immaculate appearance of a G.I. Joe doll. Bellowing is a standard method of communication for him. Its strange to see him look so small.

Come on!

Today he is impatient. Theres just a month left before we open for the summer season. The Loop is supposed to be a flagship attraction. It looks like it promises total mayhem, an illusion of risk that is the backbone of any amusement park.

Except that here, in the place my father calls Action Park, risk has never been an illusion. If something looks dangerous, thats because it is.

Andy! We dont have all day!

Paranoia enters my thoughts. There are six of us kids. Maybe six is too many. Maybe hes decided five is better.

My hands grip the edges of the Loops entrance. My father never twists my arm. He never has to. If I dont test it, hell offer an employee a hundred bucks to do it. I know its my choice, the same one he gives anybody who passes through the turnstiles. Buy the ticket, take the ride. I think Hunter S. Thompson said that, but surely, even if he were on all the drugs in the world, Hunter S. Thompson would not go down the Cannonball Loop.

I blink sweat from my eyes. The words my father recently uttered to a visiting newspaper reporter ring in my head. Im going to be the Walt Disney of New Jersey, he said, gesturing at the tangled and dysfunctional aberration he expected would launch him into amusement park history.

Being the son of the Walt Disney of New Jersey sounded pretty good, I had to admit.

I take a deep breath, tuck my arms into my chest, and do what I always do when my father calls me to action.

I jump in.

When Disneyland opened its gates for the first time on July 17, 1955, seventy million people were watching on television. In less than a years time, Walt Disney had turned 200 acres of orange groves in Anaheim, California, into a wonderland. Cinderella hugged little girls. Rides spun, and children laughed like they were on helium. A future president, Ronald Reagan, hosted the opening ceremony. Staring into the ABC cameras, Disney beamed. He had willed his $17 million dream into reality.