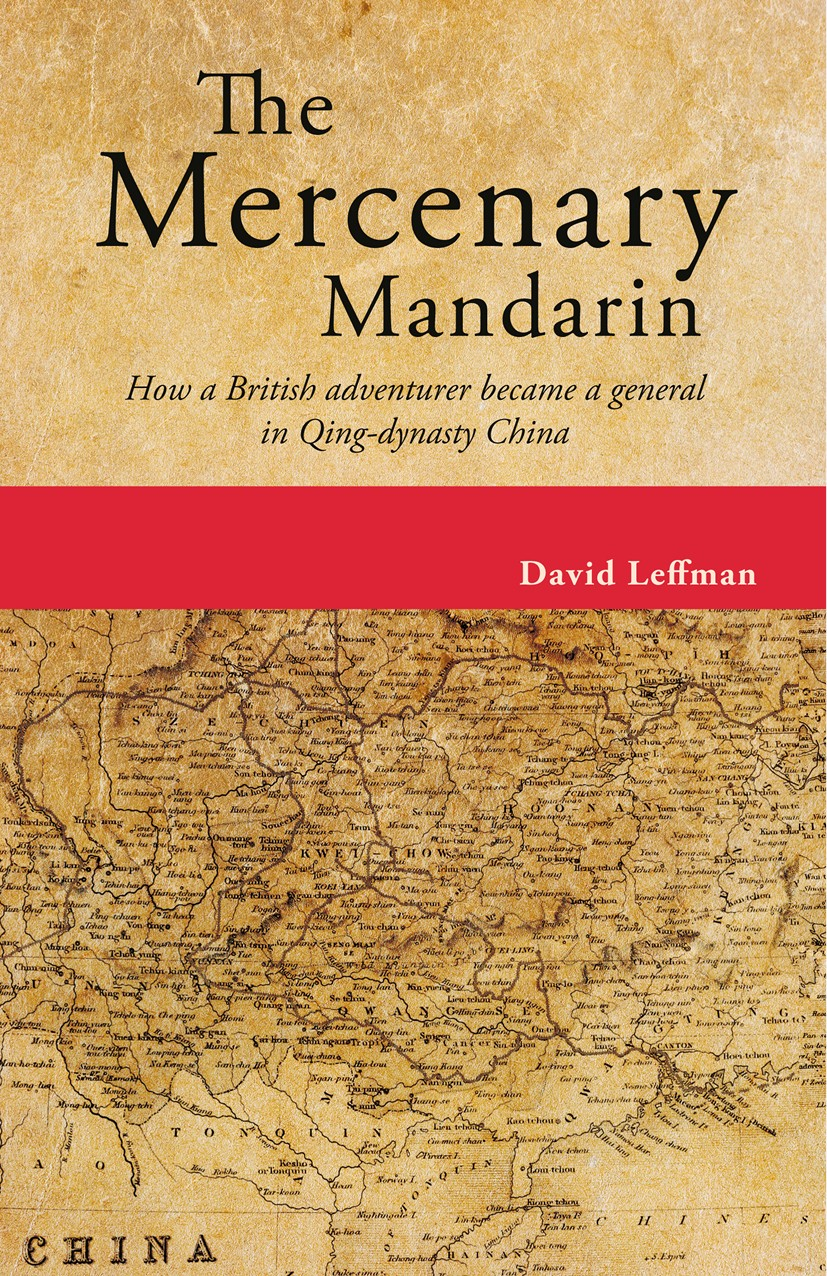

The Merce nary Mandarin

How a British adventurer became a

general in Qing-dynasty China

Davi d Leffman

Paperback ISBN 978-988-13765-4-1

eBook ISBN 978-988-75547-0-7

Published by Blacksmith Books

Unit 26, 19/F, Block B, Wah Lok Industrial Centre,

37-41 Shan Mei Street, Fo Tan, Hong Kong

Tel: (+852) 2877 7899

www.blacksmithbooks.com

Edited by Samuel Rossiter

Copyright David Leffman 2021

For hundreds of photographs, research notes and extracts from

early versions of the book, check out The Mercenary Mandarin

on Facebook or visit www.davidleffman.com.

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author

of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be

reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise,

without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Contents

I have often been told that rolling stones gather no moss, but I have a weakness for travelling, having contracted the habit when I was only nine years old.

William Mesny, 1883

Acknowledgements

F irst thanks are due to Narrell for her unwavering support, both at home and on many long trips around Chinas backblocks; and to Peter and Shelagh Hardie, who have encouraged my interest in China, art and history since 1980.

Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou by Robert D. Jenks introduced me to Mesny and the Miao war. Jim Thompson, a descendant of Mesnys sister, set up a website on Mesny (www.mesny.org) and generously provided scans of Tungking and the Miscellany on disc, without which I could never have begun to research his life.

Professor Gary Tiedemann and the late Keith Stevens shared hospitality and decades of hard-won research; in particular, Stevens 1992 biography of Mesny became the framework for my original timeline, while Professor Tiedemann alerted me to Mesnys uncredited articles in the North China Herald , encouraging me to search elsewhere for more. Tony Hadland gave feedback via his blog (hadland.wordpress.com) about his great grand-uncle, Captain William Gill; and Joyce Hill, another descendant of Mesnys sister, supplied family reminiscences and photographs.

My research was greatly helped by staff at the British Library, the National Archives at Kew, the Royal Geographical Society, the School of Oriental and African Studies Library (University of London), the Central Library and Public Records Office in Hong Kong, Macaus Leal Senado Library and the Shanghai Municipal Archives.

Id especially like to thank Anna Baghiani, Karen Biddlecombe and Gareth Syvret of Socit Jersiaise; Martin Barrow at Matheson & Co. and John Wells at Cambridge University Library; Lorna Cahill at Kew Gardens and Jonathan Gregson and Jacek Wajer at the Natural History Museum, London; Carol Westaway of the Royal Horticultural Societys Lindley Library; David of www.gwulo.com; Emily Walhout of Harvard Universitys Houghton Library; and Professor Rudolf Wagner, Ruth Wilcock and Hope Justman.

In Guizhou, Li Maoqing cheerfully interpreted from Hmong, guided me around Qiandongnan and chased down history and folklore about the Miao war. At Zhaitou village, Granny Ve Me Ou sang about the death of Guan Baoniu while Mr Wan Guoshen recited an oral history of the Dingpatang campaign and pointed out the battlefield. The Zhou family at Jiuzhou confirmed Mesnys account of the towns destruction by the Sichuan Army and retold the tale of Guo Moruos grandfather. Villagers at Shidong located sites connected with Su Yuanchun, a cook at the canteen beside Mesnys bridge at Chongan offered personal insights into the campaign, while Mr Wu Guomin, a farmer at Huangpiao, gave the Miao version of the Hunan Armys defeat. Two girls at Wengan shared a late cab ride to Niuchang along the worst main road in all China and tracked down the site of the Sichuan Army camp; villagers at Bandeng fed me sour hotpot, escorted me around Zhang Xiumeis grave and set me off down the old track down the mountain towards Shidong; Mister Wu at Jiuzhou gave directions to the flagstoned post road to Wengan; and Mr Tian Xinlong of Jiaba Niuchang village filled in details of the Jiaba campaign and told me where to find remains of the Miao stockade.

Along the way Simon Lewis, Derek Sandhaus and Paul Tomic handed out sound advice and solid backup, Wendy Van Duivenvoorde translated from Dutch and CK Lau translated from Chinese, Google Maps sometimes got things brilliantly right, and in 2012 the National Library of China published a facsimile of the complete four-volume Miscellany , some 107 years after Mesny brought out the final issue. My gratitude to Daniel Kadar for further translations and reading the manuscript through, Philip Kenny for hospitality, Chris Carroll and Mike Broom for their support, James Lucas for website design and Pete Spurrier for agreeing to publish the book.

Finally, thanks to the many, many people in China foreign expats, guesthouse owners, teachers, policemen, bus and taxi drivers, students, shop staff, martial artists, villagers, passers-by and chefs who have fed me, ferried me around, chatted to me, taught me, hit me, plied me with baijiu and otherwise helped out over the last thirty years.

David Leffman

Chinese characters and names

Theres no alphabet in Chinese: Chinese characters embody meanings, not sounds or spellings. The idea is similar to numerals in the West, where the symbol 8 means the same thing in Britain, France or Iceland regardless of local pronunciation. This way, people from different parts of China a country with many regional dialects and languages can at least communicate with each other in writing.

However, without an alphabet there is no correct way of transliterating the sounds of Chinese characters. Various systems have been used over the years, so that the Taiping leaders name written in Chinese appears in different English-language accounts as Hong Xiuquan, Hung-sui-tshuen, Hung sew tseuen and Hung Hsiu-chan.

Some Chinese place names have also changed since Mesnys day. In Sichuan, Tachienlu has become Kangding and Paoning is now called Langzhong; Guangzhou, the capital of Guangdong province, was known to the colonial British as Canton; the island village of Hwai Yuen Hsien in Guangxi province has been renamed Danzhou, and so on. Working out which settlement Mesny was talking about often involved seeking local knowledge of the old names and hours spent picking over contemporary maps.

To minimise confusion Ive used modern place names and the current standard system, pinyin , for transliterating Chinese. The main exceptions are where original sources are quoted and where historic or local names are still in use, such as Hong Kong (derived from the Cantonese pronunciation heung gong , instead of the pinyin spelling, Xiang Gang). This should make it easier to follow Mesnys journeys on a modern map, but these are not necessarily the spellings or place names used in the Miscellany or other original sources.

Brief biographies of the major players in Mesnys story can be found at the end of the book.

Foreword

I m not sure exactly when I first heard about the Miao Rebellion. I do know that I was very, very drunk.

It was springtime in southwestern Chinas Guizhou province and the Sisters Meal festival was in full swing. Thousands of Miao girls had descended from outlying villages on the small country town of Taijiang, dressed in jackets that theyd spent years embroidering in beautiful, nit-picking detail for this very event. Defying the historic Chinese norm of arranged marriages, the girls were hunting for husbands, and everything was display and competition. Proud mothers made sure that their daughters looked their best, fixing complex hairdos in place with fluorescent pink combs or, more traditionally, long silver hairpins shaped like writing brushes. Groups danced in concentric circles in the town square, the men playing long gourd pipes and banging drums, the girls jingling as they stamped to the beat underneath huge assemblages of silver necklaces and headpieces. They sang flirty, dirty songs to one another in a strange falsetto. There were buffalo fights between bulls in the surrounding paddy fields, drawing a mostly male crowd, dragon-boat races on the river for the young men to show off their strength and lantern fights at night along the main street, where village teams attempted to torch their opponents giant paper dragons with hand-held fireworks. Much collateral damage was inflicted on the crush of spectators.

![David Leffman - The Rough guide to China [2014]](/uploads/posts/book/197581/thumbs/david-leffman-the-rough-guide-to-china-2014.jpg)