Contents

Guide

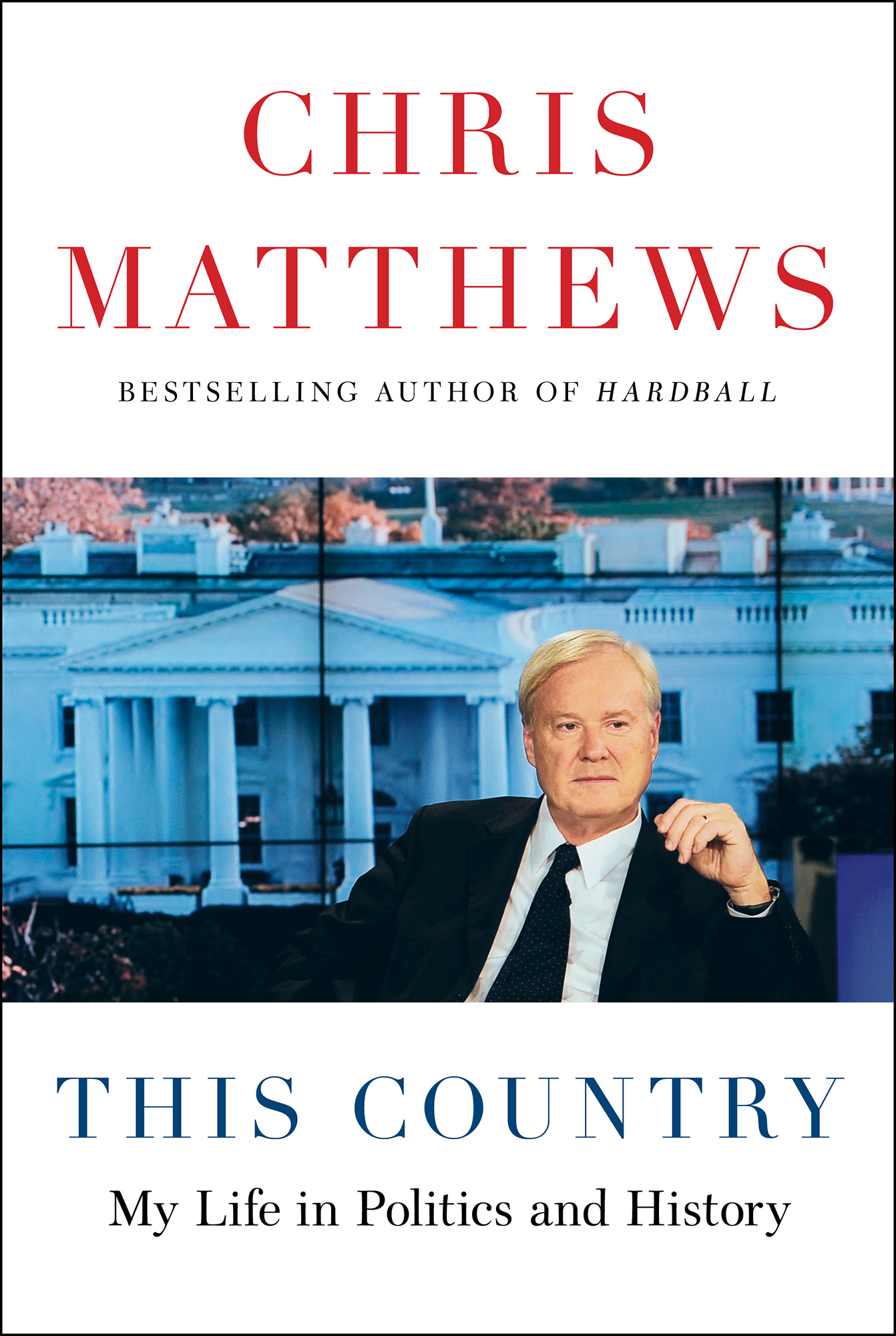

Chris Matthews

Bestselling Author of Hardball

This Country

My Life in Politics and History

ALSO BY CHRIS MATTHEWS

Hardball: How Politics Is PlayedTold by One Who Knows the Game

Kennedy & Nixon: The Rivalry That Shaped Postwar America

Now, Let Me Tell You What I Really Think

American: Beyond Our Grandest Notions

Lifes a Campaign: What Politics Has Taught Me About Friendship, Rivalry, Reputation, and Success

Jack Kennedy: Elusive Hero

Tip and the Gipper: When Politics Worked

Bobby Kennedy: A Raging Spirit

Simon & Schuster

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by Christopher J. Matthews

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Simon & Schuster Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition June 2021

SIMON & SCHUSTER and colophon are registered trademarks of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Kyle Kabel

Jacket Photographs: (Front) by The Washington Post/Getty Images; (Back) Charles Ommanney/Contact Press Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-1-9821-3484-6

ISBN 978-1-9821-3486-0 (ebook)

All photos courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

These pages are dedicated to the faithful fans of Hardball. For twenty years we shared a nightly quest for truth. You were always great company.

There are some things which cannot be learned quickly, and time, which is all we have, must be paid heavily for their acquiring.

Ernest Hemingway, Death in the Afternoon, 1932

INTRODUCTION

A lmost a half century ago, I was working in a congressional race in Brooklyn. It was a case of my doing what I was afraid to do. My instinct told me that an election campaign in the old borough might be rough, scary, even life-changing.

Brooklyn electioneering back then wasnt on the level. It was not the place for the young, clean-cut candidate I was helping make his start. Only later did the campaigns hard-boiled strategist tell me he could have bought the seat for a quarter million. It didnt shock me. A reporter for a borough weekly had previously warned me that if our candidate wanted any coverage at all, he had better pony up some ad money.

That seedy business in Brooklyn didnt kill my lifelong romance with politics. Just the opposite. As those harsh winter months of 1974 passed, I made the bold decision to make a go of it on my own. I would head home to Philadelphia and run myself.

On the face of it, the idea made no sense. I would be running against one of this countrys last big-city political machines and an entrenched US congressman who was one of its top leaders.

What gave me hope was what was happening in the country. The Watergate scandal was all over the news. Wasnt this the perfect time, if there ever would be, to offer myself as an alternative to the old ways? Who knew? Maybe the voters were in a mood to, in that time-honored phrase, throw the bums out.

What made driving across the Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge toward the New Jersey Turnpike that morning so gutsy-crazy were the hard facts. I had no moneyreally no moneyand no political backing whatsoever. I hadnt even lived at home since heading up to Holy Cross College in Massachusetts at seventeen, and, outside of my family, I didnt know a single person in the city of my birth who could help me.

The strange thing is, it wasnt all that strange for me. My life at this point had already begun to etch a pattern: take a leap, live the adventure, learn what I could. Here I was making another dive into the unknown; yet another case of doing what I was afraid to do.

What I had going for me in this instance, perhaps all I had, was a message. It was the corruptive influence of money in politics. To dramatize my crusade, I would declare that I would accept no campaign contributions whatsoever. Not only did this grab the attention of the newspapers, but it also was the heartbeat of the effortespecially among our hearty brigade of young volunteers. It put wind in my sails. While I didnt come all that close to beating the incumbent, it confirmed some powerful lessons. One is to ask. Just as Id started in Washington, DC, three years earlier by asking for someone to hire me, I learned that basic willingness to ask is what campaigning for office is all about.

A second lesson is to show up! If you want something, you have to go where its available and grab for it. Nobodys knocking on your door to connect you to your dreams. You have to knock on theirs.

With that perilous decision to drive home and run for office in the winter of 1974 I was diving deeper into the world of politics. Its a place where, having seen both the good and the bad, I still recognized the essential promise. I knew that the whole process of going out and asking someone to vote for you is the heart of our democracy. Its how the American people choose not just their leaders but also the kind of country they want to live in.

So much of what Ive written in newspaper columns and books over the years and said on Hardball for a generation comes directly from such personal adventures as that race for Congress. There were the years I spent in Africa, the campaigns from Utah to Brooklyn, my time serving the US Senate and later as a White House speechwriter for President Jimmy Carter.

It was that latter experience that continues to stir golden memories: of writing alone in my grand office in the Old Executive Office Building, having lunch at the roundtable in the White House Mess and hearing the scuttlebutt from other staffers, of working at the typewriter on Air Force One writing the presidents remarks for the next campaign stop.

Next came my once-in-a-lifetime role as a top aide to Speaker of the House Tip ONeill from 1981 through 1986. Following that were the exciting years of reporting on great historic moments, such as the Democratic and Republican conventions, the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the first all-races election in South Africa in 1994, the Good Friday peace accord in Northern Ireland in 1998, and the funeral in Rome of Pope John Paul II in 2005.

More than anything else, of course, its been a life spent watching the people running this country and those who wish they were.

I owe this life and its lessons to a half dozen leaps into the unknown.

Africa leads the list.

In June 1968 I sat alone on a public park bench in Montreal a block up from Sainte-Catherine Street and decided where I was going to go in my life. My graduate school deferment had expired. Rated 1-A in the military draft, I now listed on the back of an old business card my limited options regarding a war I opposed. I could join VISTA, the domestic volunteer program; teach high school; or enlist in the army as a public information officer. That last choice, though it required a four-year hitch, would have one big advantage: it would help me really learn how to write.