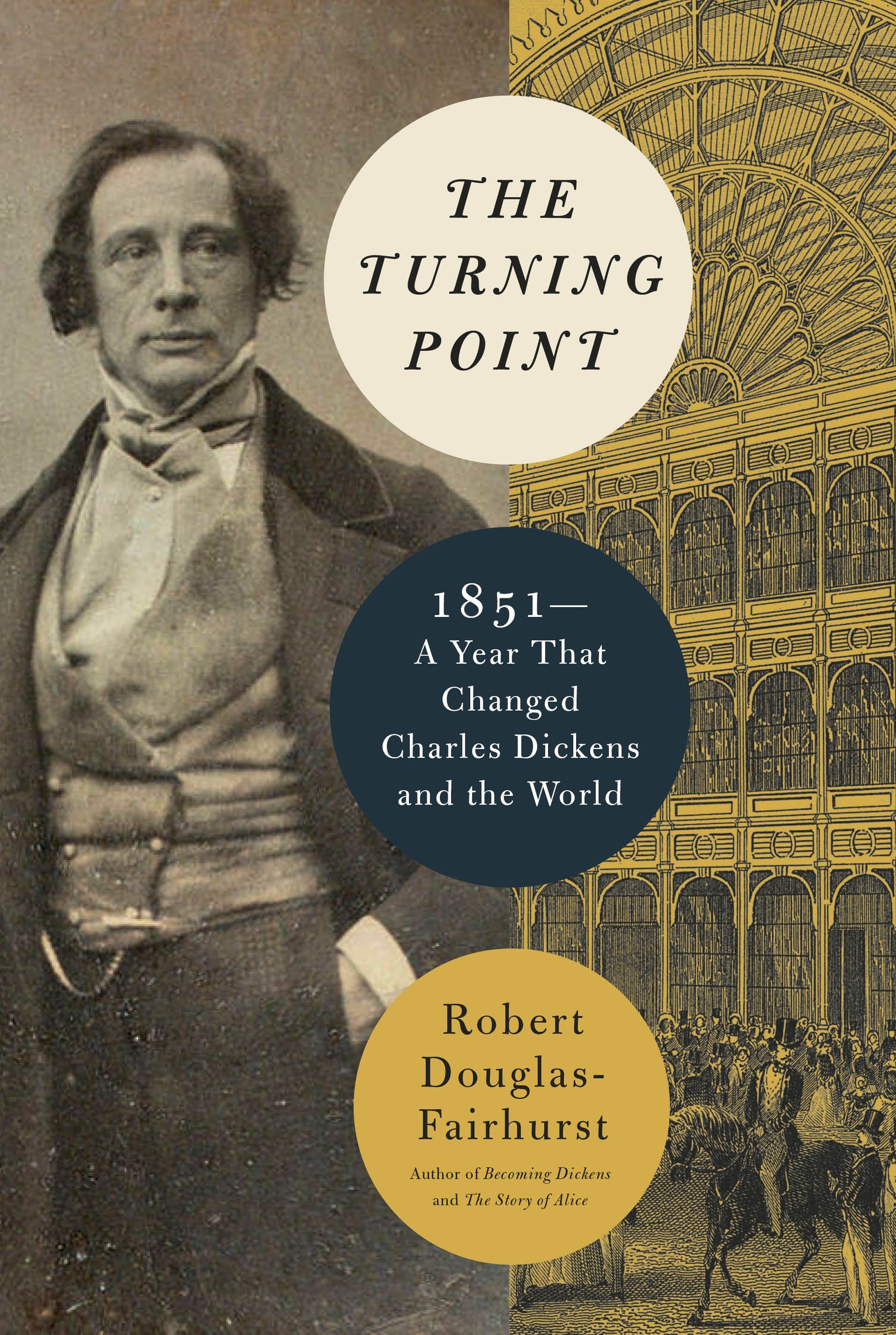

also by robert douglas-fairhurst

Victorian Afterlives: The Shaping of Influence in Nineteenth-Century Literature

Becoming Dickens: The Invention of a Novelist

The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and The Secret History of Wonderland

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2021 by Robert Douglas-Fairhurst

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage Publishing, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London, in 2021.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Douglas-Fairhurst, Robert, author.

Title: The turning point : 1851a year that changed Charles Dickens and the world / Robert Douglas-Fairhurst.

Description: First United States edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021021682 (print) | LCCN 2021021683 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525655947 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525655954 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Dickens, Charles, 18121870. | Novelists, English19th centuryBiography.

Classification: LCC PR 4582 . D 68 2022 (print) | LCC PR 4582 (ebook) | DDC 823/.8 [ B ]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021682

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021021683

Ebook ISBN9780525655954

Cover photographs: Charles Dickens by Antoine A. Claudet, courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia; engraving of the Crystal Palace, London, at the time of the Great Exhibition of 1851 Photo 12/Alamy

Cover design by Jenny Carrow

ep_prh_6.0_139378369_c0_r0

For Mac

The novelist demolishes the house of his life and uses its bricks to construct another house: that of his novel.

Milan Kundera, The Art of the Novel

Contents

London. December 1850. So far it has been an unusually mild winterin Kensington there are reports that a tree is already sending out the first green shoots of spring. Not that everyone can see them. In fact some people can scarcely see past their own feet. Fog. Its dirty fingers probe and stroke the buildings, and make a ghost of anyone who ventures outside. It muffles the sounds of everyday life: the distant cries of street sellers, the clockwork chime of church bells, the steady rattle of horse-drawn cabs punctuated by the curses of foot passengers slipping on wet pavements. It is beautiful: in some places it is pale yellow or green in colour, creating halos around the hissing gas jets and turning every street scene into an impromptu stage set. It is also dangerous: on the evening of 23 December there is a collision in dense fog between two trains near Brick Lane, causing many passenger injuries after a carriage is shattered in all directions. Fog everywhere.

Approaching the end of one year and the start of the next, the nation is getting used to seeing life as a series of pivots between the old and the new. Joseph Paxtons Crystal Palacea nickname coined that summer by the playwright and wit Douglas Jerroldis rapidly being assembled in Hyde Park, and already it is one of the most remarkable sights in London: a giant glass bubble wrapped around a cast-iron skeleton, like an experimental skyscraper gathering its strength for a final push upwards. On the ground there is a steady bustle of activity, as girders are bolted together and glass panels are slotted into place. Excitement about the forthcoming Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations is also building. The Illustrated London News is carrying advertisements for sheet music featuring The Great Exhibition Polka, and it is also possible to buy a Grand Authentic View of the Crystal Palace engraved on steel nearly Two Feet in Lengthalthough that is a mere dolls house design compared to the real building, which when completed will be 1,848 feet long by 456 feet wide, or roughly three times the size of St. Pauls Cathedral.

Elsewhere things are not progressing nearly so fast. Although mortality rates are falling, the latest official statistics show that they remain considerably higher in cities like London than elsewhere in the country, largely because of the diseases spread by contaminated water and overflowing graveyards. (A recent outbreak of cholera in Jamaica has given a terrible warning of what can happen when a city is gripped by infectious disease: in Kingston more than two hundred people have been dying every day, and with no more coffins left their bodies have been rotting in heaps under the tropical sun.) In December a young servant hired from the local workhouse achieves an unhappy kind of fame when it is revealed that she has been so badly mistreated by her employerswho have starved her, beaten her, and forced her to eat her own excrementthat when she is rescued the hospital surgeon who examines her declares that she is the most perfect living skeleton I have ever seen. The newspapers are also full of reports describing how the convict George Hacket has recently escaped from Pentonville Prison, after levering up a part of the chapel floor and hauling himself down the prison wall using a rope made from knotted sheets; the next evening he sends a letter to the prison governor, in which he presents his compliments and announces that he is in excellent spirits and in a few days intends to proceed to the continent to recruit his health. For all the visible signs of progresseverywhere ambitious modern buildings are rising out of the rubble of construction sites, and the streets are full of fresh scars as new sewers and gas pipes are laidin some ways not much appears to have changed since the notorious thief Jack Sheppard achieved folk-hero status by repeatedly escaping from prison more than a century earlier.

The literary world is also caught between the old and the new. At her house in Chester Square, Mary Shelley is suffering from the brain tumour that will kill her in a matter of weeks; in her writing desk is a copy of Shelleys poem Adonais, wrapped around a silk parcel containing the charred remains of his heart and some of the ashes from his cremation on an Italian beach in 1822. Leigh Hunt, formerly a political radical and Keatss literary mentor, has recently celebrated his sixty-sixth birthday with the publication of a three-volume autobiography, in which he boasts that over a career spanning more than four decades he has somehow managed to avoid ever growing up: accused of being the spoiled child of the public, he claims this is a title he is proud to possess. At the same time there are signs the Romantic age is finally giving way to a more modern alternative. Alfred Tennyson has recently become Poet Laureate, following Wordsworths death in April and the 86-year-old Samuel Rogers declining the office on account of his great age, with Tennyson only deciding to accept after Prince Albert came to him in a dream and kissed him on the cheek. (I said, in my dream, Very kind, but very German.) The same month a revised edition of Elizabeth Barrett Brownings