TWELVE CAESARS

THE TWELVE CAESARS

TWELVE CAESARS

IMAGES OF POWER FROM THE ANCIENT WORLD TO THE MODERN

MARY BEARD

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

THE A. W. MELLON LECTURES IN THE FINE ARTS

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON

Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Bollingen Series XXXV: 60

Copyright 2021 by Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorised edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

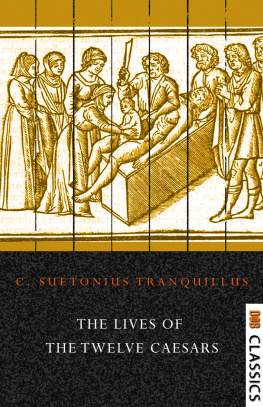

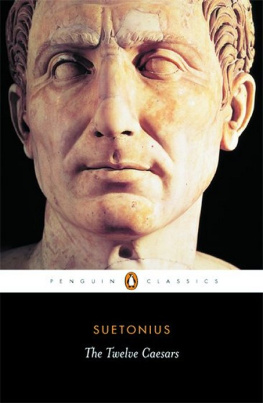

Jacket art (front): Shutterstock, (back): Edition of Suetoniuss Twelve Caesars , printed in Rome, 1470; the binding c. 1800, with Augsburg enamels c. 1690 after Sadelers Twelve Caesars inset into the inside front cover. Collection of William Zachs, Edinburgh. Photo courtesy of Sothebys London.

Jacket design by Faceout Studio, Molly Von Borstel

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Beard, Mary, 1955- author.

Title: Twelve Caesars : images of power from the ancient world to the modern / Mary Beard.

Description: Princeton : Princeton University Press, [2021] | Series: The A.W. Mellon lectures in the fine arts ; 2011 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012740 (print) | LCCN 2021012741 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691222363 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780691225869 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Kings and rulersPortraits. | Power (Social sciences) in art. | EmperorsRomePortraits. | Art, RomanInfluence. | BISAC: HISTORY / Ancient / Rome | ART / History / General

Classification: LCC N7575 .B38 2021 (print) | LCC N7575 (ebook) | DDC 709.02/16dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012740

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012741

Version 1.0

This is the sixtieth volume of the A. W. Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts, which are delivered annually at the National Gallery of Art, Washington. This volume is based on lectures delivered in 2011. The volumes of lectures constitute Number XXXV in the Bollingen Series, supported by the Bollingen Foundation.

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Designed by Jeff Wincapaw

For the American Academy in Rome

with gratitude and happy memories

Contents

- viii

- ix

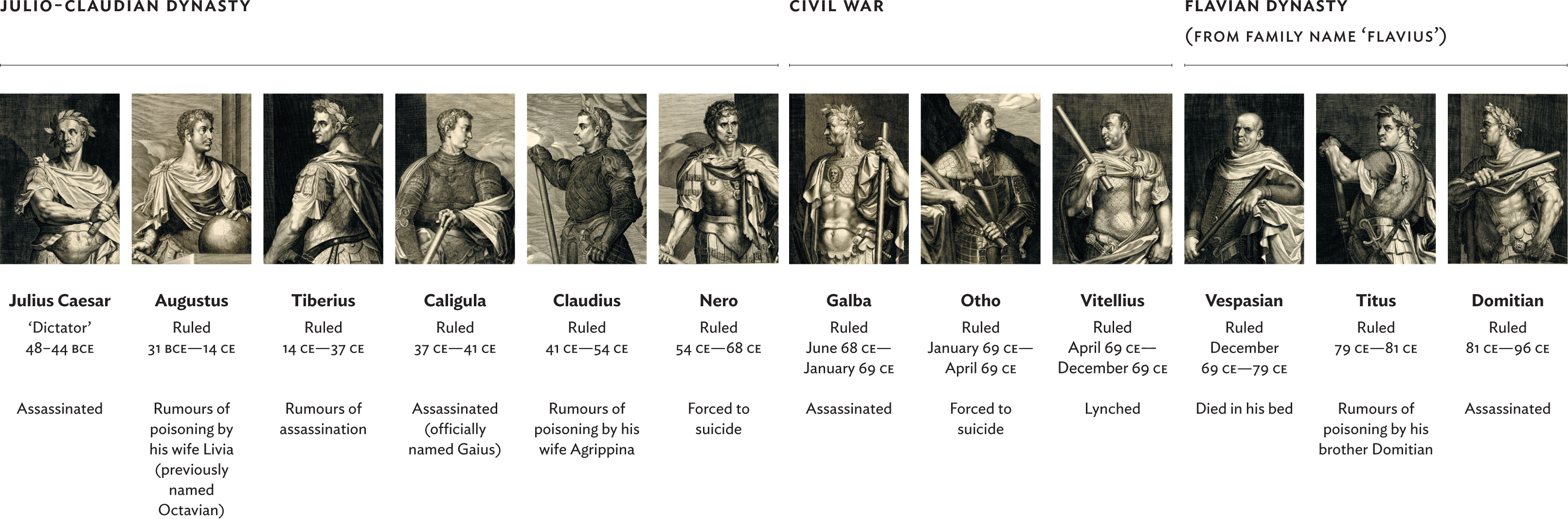

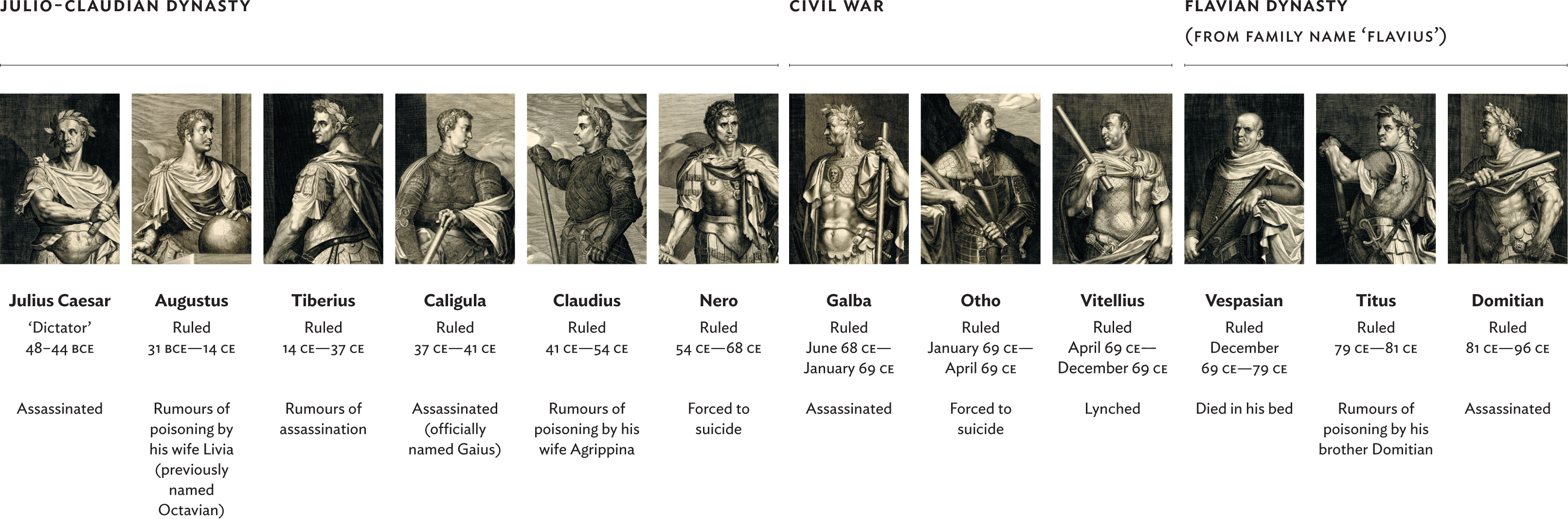

Tables

Preface

We are still surrounded by Roman emperors. It is now almost two millennia since the ancient city of Rome ceased to be capital of an empire, but even nowin the West at leastalmost everyone recognises the name, and sometimes even the look, of Julius Caesar or Nero. Their faces not only stare at us from museum shelves or gallery walls; they feature in films, advertisements and newspaper cartoons. It takes very little (a laurel wreath, toga, lyre and some background flames) for a satirist to turn a modern politician into a Nero fiddling while Rome burns, and most of us get the point. Over the last five hundred years or so, these emperors and some of their wives and mothers, sons and daughters, have been recreated countless times in paint and tapestry, silver and ceramic, marble and bronze. My guess is that, before the age of mechanical reproduction, there were more images in Western art of Roman emperors than of any other human figures, with the exception of Jesus, the Virgin Mary and a small handful of saints. Caligula and Claudius continue to resonate across centuries and continents in a way that Charlemagne, Charles V or Henry VIII do not. Their influence goes far beyond the library or lecture room.

I have lived more intimately than most people with these ancient rulers. For forty years now they have been a large part of my job. I have scrutinised their words, from their legal judgements to their jokes. I have analysed the basis of their power, unpicked their rules of succession (or lack of them), and often enough deplored their domination. I have peered at their heads on cameos and coins. And I have taught students to enjoy, and to interrogate closely, what Roman writers chose to say about them. The lurid stories of the emperor Tiberiuss antics in his swimming pool on the island of Capri, the rumours of Neros lust for his mother or of what Domitian did to flies (torture with them with his pen nib) have always gone down well in the modern imagination and they certainly tell us a good deal about ancient Roman fears and fantasies. Butas I have repeatedly insisted to those who would love to take them at face valuethey are not necessarily true in the usual sense of the word. I have been by profession a classicist, historian, teacher, sceptic and occasional killjoy.

In this book, I am shifting my focus, onto the modern images of emperors that surround us, and I am asking some of the most basic questions about how and why they were produced. Why have artists since the Renaissance chosen to depict these ancient characters in such large numbers and in such a variety of ways? Why have customers chosen to buy them, whether in the form of lavish sculptures or cheap plaques and prints? What do the faces of long-dead autocrats, many more with a reputation for villainy than for heroism, mean to modern audiences?

The ancient emperors themselves are very important characters in the chapters that follow, especially the first Twelve Caesars, as they are now often knownfrom Julius Caesar (assassinated in 44 BCE) to the fly-torturing Domitian (assassinated in 96 CE), via Tiberius, Caligula and Nero, among others (). Almost all the modern works of art that I discuss were produced in dialogue with the Romans own representations of their rulers, and with all those ancient stories, far-fetched though they might be, of their deeds and misdeeds. But in this book the emperors themselves share the spotlight with a wide range of modern artists: some, like Mantegna, Titian or Alma-Tadema, are well known in the Western tradition; others are drawn from generations of now anonymous weavers, cabinet-makers, silversmiths, printers and ceramicists who created some of the most striking and influential images of these Caesars. They share the spotlight too with a selection of the Renaissance humanists, antiquarians, scholars and modern archaeologists who have turned their energies to identifying or reconstructingwrongly or rightlythese ancient faces of power, and with the even wider range of people, from cleaners to courtiers, who have been impressed, enraged, bored or puzzled by what they saw. In other words, I am not only interested in the emperors themselves or in the artists who have recreated them, but in the rest of us who look.

There are, I hope, some surprises in store, and some unexpectedly extreme art history. We shall be meeting emperors in very unlikely places, from chocolates to sixteenth-century wallpaper and gaudy eighteenth-century waxwork. We shall be puzzling over statues whose date is even now so disputed that no one can agree whether they are ancient Roman, modern pastiches, fakes or replicas, or creative Renaissance tributes to the imperial tradition. We shall be reflecting on why so many of these images have been imaginatively re-identified or persistently confused over hundreds of years: one emperor taken for another, mothers and daughters mixed up, female characters in the history of Rome (mis)interpreted as male, or vice versa. And we shall be reconstructing, from surviving copies and other faint hints, a lost series of Roman imperial faces from the sixteenth century, which are now almost universally forgotten, but which were once so familiar that they defined how people across Europe commonly imagined the Caesars. My aim is to show why images of these Roman emperorsautocrats and tyrants though they may have beenstill