Published in the United States of America and Great Britain in 2021 by

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS

1950 Lawrence Road, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

and

The Old Music Hall, 106108 Cowley Road, Oxford OX4 1JE, UK

Copyright 2021 Ken Conboy

Hardback Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-019-0

Digital Edition: ISBN 978-1-63624-020-6

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in the United States by Sheridan

For a complete list of Casemate titles, please contact:

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (US)

Telephone (610) 853-9131

Fax (610) 853-9146

Email:

www.casematepublishers.com

CASEMATE PUBLISHERS (UK)

Telephone (01865) 241249

Email:

www.casematepublishers.co.uk

Contents

Acknowledgements

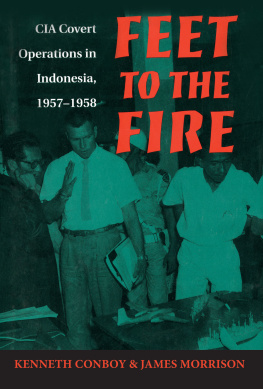

During the Cold War, the Central Intelligence Agencys largest and longest-running paramilitary operation was in the tiny kingdom of Laos. Hundreds of its advisors and support personnel trained and led guerrilla formations across the mountainous Laotian countryside, as well as ran smaller road-watch and agent teams that stretched from the Ho Chi Minh Trail to the Chinese frontier. Added to this number were hundreds of contract personnel providing covert aviation services.

It was dangerous work. On the Memorial Wall at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia, nine stars are dedicated to officers who perished in Laos. Added to this are more than one hundred people from proprietary airlines killed in aviation mishaps between 1961 and 1973. Combined, this grim casualty figure is orders of magnitude larger than that of any other CIA paramilitary operation.

But for the foreign intelligence officers of the CIA, Laos was more than a paramilitary battleground. Because of its geographic location as a buffer state, as well as its trifurcated political structure, Laos was a unique Cold War melting pot. All three of the Lao political factions, including the communist Pathet Lao, had representation in Vientiane. The Soviet Union had an extremely active embassy in the capital, while the Peoples Republic of Chinathough in the throes of the Cultural Revolutionhad multiple diplomatic outposts across the kingdom. So, too, did both North and South Vietnam.

All of that made for fertile ground for clandestine operations. This book details, for the first time, the cloak-and-dagger side of the war in Laos, from agent recruitments to servicing dead drops in Vientiane. It is important that this story be told for several reasons. First, clandestine operations in Laos were often in support of the wider Indochina campaign, and an analysis of these operations adds to a better understanding of the CIAs contribution during the Second Indochina War.

Second, some of these operations were tied to Americas overarching Cold War struggle; for example, against the Soviet Union and Warsaw Pact. In one case, a recruitment started in Laos ranks among the most important CIA penetrations of the Soviet intelligence services. Understanding these operations in Laos allows for a fuller reading of the CIAs historical competition with its communist counterparts.

Finally, many of the CIA personalities in Laos went on to prominence within the Agency and factored in major operations outside of Southeast Asia. Understanding their experiences in Laos permits for a greater appreciation of what they accomplished elsewhere.

This book is based on both written sources and interviews. Special thanks go to Soutchay Vongsavanh, who was extremely generous with his time and extraordinary support. Thanks, too, go to Merle Pribbenow for his unparalleled insights into Vietnamese military history. I also extend my sincere gratitude to Dan Arnold, Barry Broman, Albert Grandolini, Peter Koret, Kevin McCarthy, Arya Panya, Song Ramawati, Martin Rathie, Ousa Sananikone, Veera Star, Christopher Tovar, James Tovar, and Maya Velesko. Finally, I owe a continuous debt to Charn Wisezjanthe ever-resourceful Albertfor his unwavering support and invaluable commentary.

Research for this book took place over more than a decade. Sadly, several of those who were instrumental in my research have passed away in the interim. I would like to draw attention to the help, and especially friendship, of the late Jim Dunn, Jim Morrison, Soui Sananikone, MacAlan Thompson, and B. Hugh Tovar. They are truly missed.

CHAPTER 1

Growing Pains

Laos was a most improbable nation to transfix the superpowers of the mid-20th century. A landlocked patch of mountainous territory roughly the size of Great Britain, it had its heyday six hundred years earlier when local royalty rose to prominence under what was called Lan Xang, the Kingdom of a Million Elephants. Back then it had flourished as a center for the arts and Buddhist theology. Equally impressive was Lan Xangs military prowess, its warriors extending the kingdoms reach over most of current-day Laos, northern and central Thailand, and northern Cambodia.

By the 16th century, however, Lan Xangs fortunes began to wane as it was weakened in a series of wars with the Burmese. Three centuries later, continued foreign pressure, compounded by palace intrigue, split the kingdom in three.

Thus broken, the once-formidable Lan Xang was a sparsely populated backwater when the French traveled up the Mekong River in the latter half of the 19th century. Though the fractured principalities had few economic benefits to offer, France needed a buffer to shield its lucrative Vietnamese holdings from the expansionist Thai and the British in Burma. The French, then, fused the landlocked realms back together into a single protectorate and created Laos. As its titular leader, the king in Luang Prabang was elevated as the unified Lao monarch.

Under French rule, Laos barely developed beyond its frontier status. A handful of dirt roads, passable only in the dry season, were cut on an eastwest axis to the Vietnamese coast. A single northsouth road, Route 13, was not completed until 1943. While Vietnamese laborers were imported to mine tin, and coffee and corn were grown on the Bolovens Plateau, products from Laos never represented more than 1 percent of total French exports from its Southeast Asian colonies.

With few resources to exploit, the Lao population was all but ignored by the French. And while the king of Laos was allowed to retain nominal control around Luang Prabang, in practice the French ruled Laos as would a benign and indifferent absentee landlord, retaining the existing traditional village structure and introducing hundreds of educated Vietnamese to run the country on a daily basis.

As for the apolitical Lao peasantry, most of whom had little interest in events outside their village, French indifference was matched in kind. Indeed, only two disturbances of any significanceboth involving hill tribesbroke the peace during nearly a half century of French rule. These relatively minor events aside, Laos was as close as the French got to a perfect protectorate. At little cost, they had a nearly trouble-free bufferuntil World War II.