Preface

New Light on Old Stories

For last years words belong to last years language

And next years words await another voice.

T. S. Eliot, Little Gidding

Lost segments of New Englands past await discovery in the scattered records of its meetinghouses. The first in early colonial settlements witnessed Sabbath lessons and prayers, town meetings and court hearings, militia drills and punishments. Today documents tucked away in libraries, archives, and attics help piece together the events, controversies, and personalities that shaped developing towns and their churches. Forgotten voices survive in sermons, in town and parish records, in wills, deeds, and court testimonies, in newspapers, diaries, and family letters. They speak of scripture and salvation, liberty and taxes, controversy and scandal, patriotism and privilege, enslavement and exclusion. Despite the passage of time, these primary accounts of religious duty, moral behavior, and civic responsibility retain a startling familiarity.

This book tells the story of four consecutive meetinghouses, no longer standing, that defined the religious and secular life of a prominent Connecticut town over 250 years. Established by the colonys General Court in 1665/6, the town called Lyme (later Old Lyme), initially covered more than eighty square miles of forest, meadow, and salt marsh at the mouth of the Connecticut River. By then in 1637 led a colonial force that torched their village near the Mystic River, incinerating elders, women, and children.

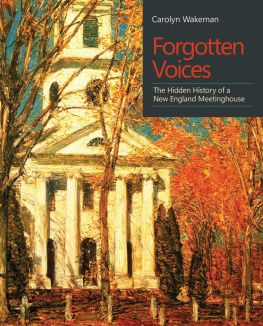

Three decades later had negotiated with Mohegan chief Uncas for lands stretching north along the Connecticut River and east along Long Island Sound and chose a hilltop location for their first public gathering place. Until a fire caused by a lightning strike destroyed the third meetinghouse on that site, Lymes colonial inhabitants prayed, sang, argued, voted, judged, and disciplined in a combined church, community hall, and justice court. A stately fourth meetinghouse with pillared faade and soaring spire, built in 1817 a mile west at the junction of the towns two highways, excluded secular gatherings. Funded by prospering parishioners with increasingly cultivated tastes, the new edifice was designed as a house of God.

As tourism developed after the Civil War and a railroad bridge across the Connecticut River improved access to the coastal town, metropolitan remarked about Hassams Church at Old Lyme.

Over the centuries, what transpired within the towns meetinghouse walls slipped from view. To explore a forgotten past, I searched for voices that reached across the decades to reveal what people thought, why they acted, and how they responded to changing circumstances, values, and opportunities. My search began when Lymes first church, now the First Congregational Church of Old Lyme, celebrated its 350-year history in 2015. Existing accounts left me uncertain about church beginnings, curious about what had unfolded inside early meetinghouses, and intrigued by the role of public memory in the prevailing narrative. Booklets and family memoirs offered summary information and flattering anecdotes about acclaimed ministers and prominent residents. More probing local histories added documentation and depth, but gaps waited to be filled, emphases reconsidered, and assumptions challenged. To shed new light on old stories, I searched for details, connections, and contexts.

Forgotten Voices gathers short passages from period texts to reexamine, expand, and personalize the local past. Whether a memorial to the colonial legislature about Christianizing Indian families, a Revolutionary-era sermon posing the alternatives of independence or slavery, a faded notebook detailing the formation of a Female Reading Society, or a brief notation about erasing church records to obscure anti-abolition views, the selected passages convey decisions and beliefs that resonate beyond the confines of one Connecticut town. Ties of marriage, commerce, education, and faith connected local families to New Englands centers of influence and power, to the cotton-rich South and the developing West, to New York and Barbados, London and Canton. Words that echo from Lymes pulpits, pews, parlors, and taverns detail events that shaped a particular community but also sketch the regional contours of the evolving American experience.

Accompanying images make distant lives and times visible. The mark of an enslaved woman consenting to her deed of sale, a hand-drawn map of the towns parishes, a wooden box that transported tea from Canton, the pocket Bible carried by a Civil War recruit, a nostalgic cover illustration for the Ladies Home Journal, all pull a forgotten past into present focus. The surviving documents, objects, photographs, and paintings also prompt reflection on what remnants and representations of the past survive and what is missing from the visual record.

Silences spoke loudly as I searched for meetinghouse voices. Ministers, judges, and merchants, the dominant landowners whose public influence defined the towns religious and secular affairs, spoke clearly and authoritatively in sermons, church records, town meeting reports, and court decisions. Womens reflections, while publicly muted, filled family letters and lingered in journals, albums, and scrapbooks. The voices of those marginalized and enslaved echoed faintly from birth records, baptismal lists, property transactions, runaway notices, and grave markers in the town where three branches of my family had settled in the 1660s.

I remembered a fourth-grade class trip to Meetinghouse Hill, where no trace of the towns first gathering place remained and a country club offered scenic views of the Connecticut River. We children peered through the underbrush at a mile marker left by Benjamin Franklins postal route surveyors measuring the distance to New London. We examined lichen-crusted inscriptions on crumbling gravestones in an early cemetery. We learned that the hilltop location had provided protection from Indian attack. We did not learn about the systematic elimination of Native American presence or that the towns ministers and prominent families owned enslaved servants for a century and a half. We had no idea that in the third meetinghouse on that site, seats for the black people in the corners of the rear gallery had been raised only in 1814 so they could see the minister. Even today, when scholars articulate the consequences of settler colonialism and document the persistence of chattel slavery in Connecticut, its local impact has largely disappeared from public memory.

As my search for the meetinghouse past brought startling discoveries about privilege and power, about the intersection of private lives and public actions, about habits of memory and forgetting, its history continued to evolve. When a Pakistani couple in New Britain, the taxpaying owners of a successful pizza restaurant, received notice of impending deportation for an alleged visa violation, the towns fifth meetinghouse became literally a sanctuary. Church members in 2018 invited Sahida Altaf and Malik bin Rehman to set up housekeeping in a former Sunday school classroom. Their five-year-old daughter Roniya, an American citizen, joined them on weekends while the immigration appeals process worked its way through the courts. For seven months, until the deportation order was temporarily lifted, the threatened South Asian immigrant family remained sequestered. An ankle bracelet assured that Malik would not step outside. When award-winning author and journalist Dave Eggers reported the story in the