RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Louisa Lim

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission from MC Yan to reprint the lyrics from 2019.

Photo on reprinted by permission of Patrick Cummins.

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lim, Louisa, author.

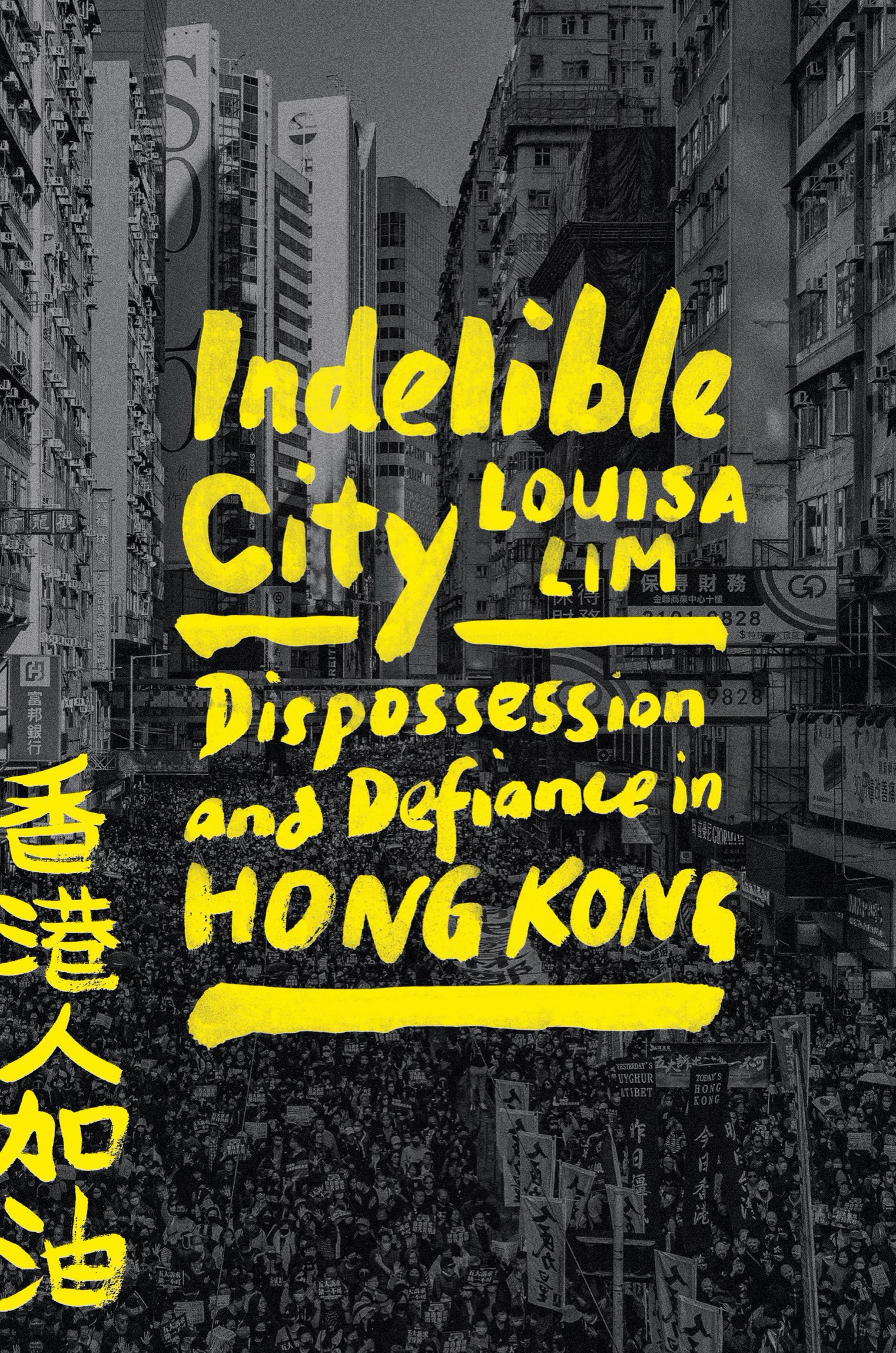

Title: Indelible city : dispossession and defiance in Hong Kong / Louisa Lim.

Other titles: Dispossession and defiance in Hong Kong

Description: New York : Riverhead, 2022. |

Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021039690 (print) | LCCN 2021039691 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780593191811 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593191835 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Protest movementsChinaHong KongHistory. |

Hong Kong (China)Social conditions. | DissentersChinaHong Kong. |

Social movementsChinaHong KongHistory. |

Hong Kong (China)Politics and government.

Classification: LCC HN752.5 L54 2022 (print) | LCC HN752.5 (ebook) |

DDC 303.48/4095125dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021039690

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021039691

cover design: l. huang

book design by lucia bernard, adapted for ebook by shayan saalabi

pid_prh_6.0_139713515_c0_r0

To all those who really fucking love Hong Kong

i dont think i can get the land back.

The King of Kowloon

your furious characters on the red postbox kindle in us a flame we have always known.

King of Kowloon by Jennifer Wong

Contents

Authors Note

Although I lived in Hong Kong for almost all my childhood and some of my adulthood, I am not a native Hong Konger, and I no longer live in the city. My position on the sidelines liberates me to write more openly than others. However, my freedom must not come at the cost of my sources. Nowadays the act of writing about Hong Kong has become an exercise in subtraction. Though the interviews for this book, unless otherwise stated in the text, were carried out prior to the introduction of the national security legislation in June 2020, the broad and retrospective application of the legislation has compelled me to remove some names and details from the text nevertheless, to protect those with whom I spoke.

This act of stripping away the identities of interviewees is all the more painful because my aim in writing this book was to place Hong Kongers front and center of their own narrative. Yet in this national security era, writing about Hong Kongs distinct identity is land-mined with risk. Indeed, many of Hong Kongs best writers can no longer find the words, or even the platforms, to express themselves openly. This book owes its existence to all those who spoke to me, both named and unnamed. I hope I am honoring the truth of their words while being mindful of their safety.

PROLOGUE

I was squatting on the roof of a Hong Kong skyscraper, sun blazing on my head, sweat dripping into my eyes, painting expletive-laden Chinese characters onto a protest banner eight stories high and wondering if I had just killed my career in journalism. The air was soupy with heat, and through the haze I could see a satisfying Tetris-scape of rooftops packed so tight they seemed to interlock. Id come to the rooftop to interview a secret cooperative of guerrilla sign painters who specialized in producing mammoth pro-democracy banners to be slung from Hong Kongs highest peaks. But as I watched, my fingers itched to grab a paint brush and join in.

It was the autumn of 2019, the day before Chinas National Day, commemorating the seventieth anniversary of the establishment of the Peoples Republic of China on October 1, 1949. For months, millions of people had marched through Hong Kongs streets, in the biggest and most sustained anti-government protests the territory had ever seen. After 155 years as a British colony, Hong Kong had been returned to China in 1997, in an unprecedented transition of sovereignty. Although Beijing had vowed that Hong Kong could preserve its way of life for fifty yearsuntil 2047China was now threatening to ram through legislation that would renege on that promise.

The secret band of calligraphers had been busy deploying their team of rock climbers to scale Hong Kongs crags in the dead of night, so that people woke up to gigantic signs exhorting them to Take to the Streets to Oppose the Evil Law or Fight for Hong Kong. The sheer scope of the banners turned the territory itself into a canvas and reinvigorated the protest movement when morale was ebbing. Id always been fascinated by the audacity of the sign painters, but I had no idea who they were or how to get in touch with them. That morning, someone who knew of my obsession had contacted me out of the blue to invite me to watch them in action. It was an offer I couldnt refuse.

The sunbaked rooftop of this tall building offered both the privacy and the expanse necessary to lay out the huge banners and dry them. There were seven sign painters. I had promised not to divulge any details that might expose their identities, but I was surprised that instead of the young, athletic radicals of my imagination, they were older men and women whose familiarity with one another was evident in the wordless efficiency of their interactions. Working quickly, they unfolded a gigantic bolt of thick black cotton, then used their feet to stamp the material flat on the roof in a brisk, communal dance. They placed rocks along the edges to hold the cloth still. Then an elderly calligrapher began sketching out the characters in white chalk. Moving with a fluid grace, the writers entire body mirrored the strokes of a calligraphy brush dancing across the fabric as the piece of chalk dipped and curved, tracing the outline of four enormous Chinese characters.

As the final ideogram took shape, I couldnt help but snort with laughter. The words the calligrapher was so carefully inscribing on the banner were , a sweary and wholly untranslatable pun in Cantonese, the dominant language spoken in Hong Kong and parts of southern China. A literal translation would be Celebrate their mother! but this was actually a pun playing on the most popular Cantonese insult: , or Fuck your mother! So the actual meaning of the banner was something along the lines of Fuck your motherfucking National Day celebrations! In other words, the slogan was calculated to cause maximum offense, by mocking the massive military parade to be held in Beijing and at the same time underscoring that Hong Kongers did not consider themselves part of the Peoples Republic of China. It was an irreverent slap in the face that was simultaneously laugh-out-loud funny and deadly serious, not least because, if caught, the sign painters could face jail time.