Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

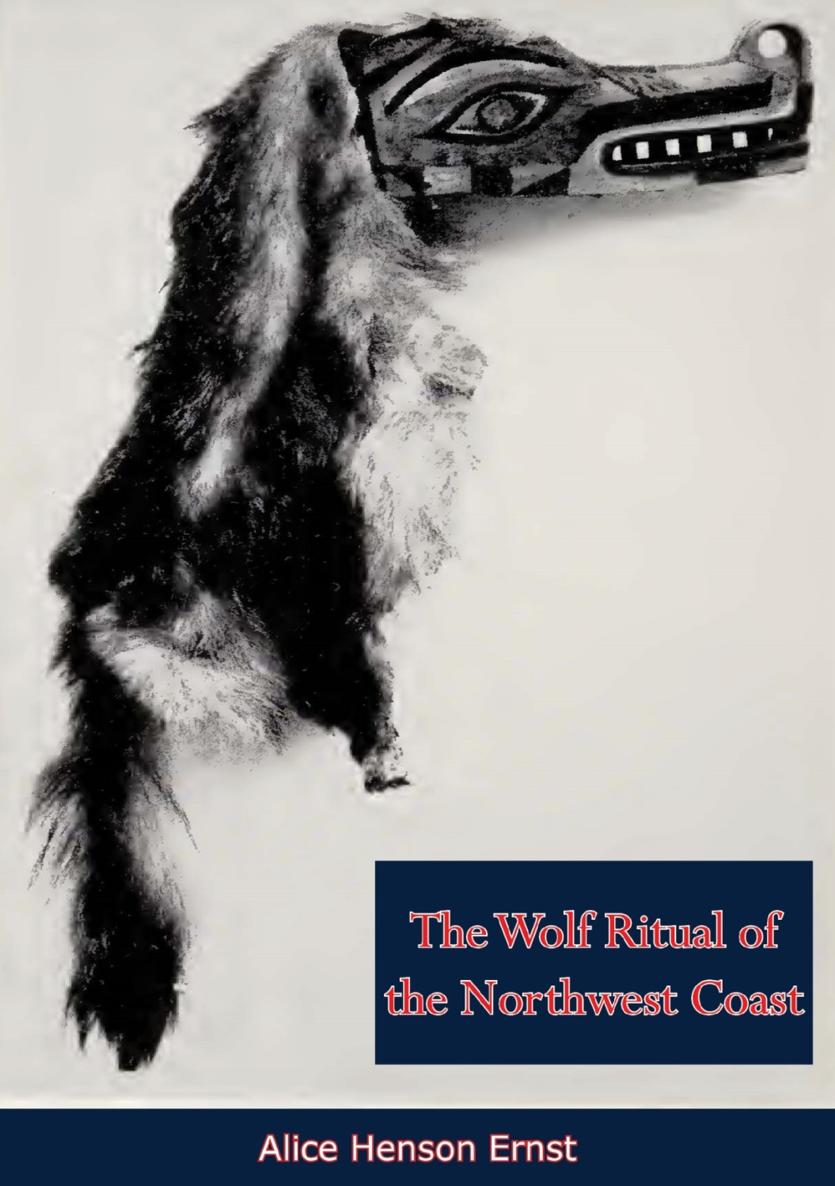

THE WOLF RITUAL OF THE NORTHWEST COAST

BY

ALICE HENSON ERNST

PLATES

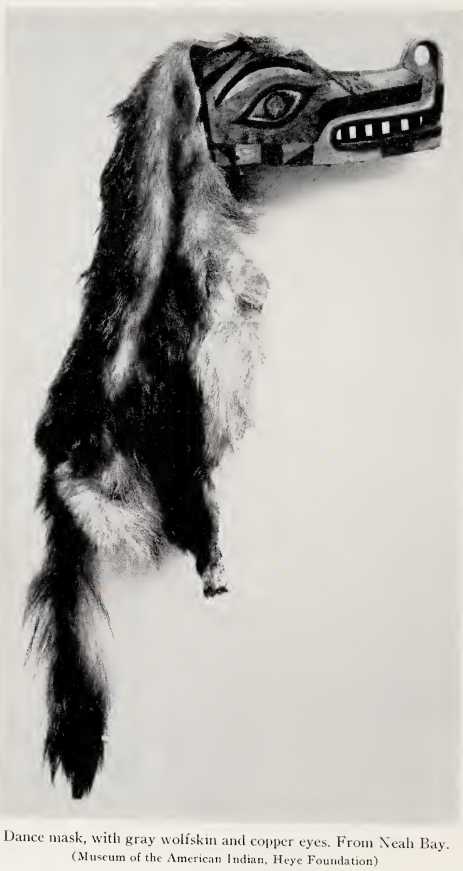

Frontispiece. Dance mask, with gray wolfskin and copper eyes. From Neah Bay

Plate I. The black animal-head mask, worn in the Crawling Wolf Dance. From Neah Bay

Plate II. The solid-type Wolf mask (Makah)

Plate III. Realistic Makah Wild Man mask

Plate IV. Stylized Makah Wild Man mask

Plate V. A Makah mask representing the Other Wild Man or The Destroyer

Plate VI. The Makah Dog mask

Plate VII. A small Makah festival Wolf mask

Plate VIII. Huge Makah festival Wolf mask

Plate IX. Eagle mask with nose adornment

Plate X. Ancient Quillayute Wild Man mask

Plate XI. Old Quillayute shamans wand

Plate XII. Quillayute Wolf mask

Plate XIII. Quillayute Wolf-head baton

Plate XIV. Rare mask, with human face, wearing the Wolf mask on the forehead

Plate XV. Nootkan Wild Man mask

Plate XVI. The Lightning Serpent or Belt of the Thunderbird mask (Clayoquot)

Plate XVII. Nootkan festival Wolf mask

Plate XVIII. Kwakiutl dancer with mask and accessories

Plate XIX. Nootkan dancer wearing the Huk-luksim mask and robe representing Thunderbird

PREFACE

THE material included in the present study was assembled during successive summers from 1932 to 1940, from field work along the Northwest Coast. The actual record began much earlier, with childhood impressions of scenes in the background of a pioneer family exchanging an eastern city for the frontier Olympic Peninsula. The migrant Clallams, moving between summer fishing grounds and winter villages, were familiar figures, and two coast Indian reservations (those of the Makahs and Quillayutes) horizon boundaries like mountain or sea. Beating drums and strange masks used in ritual dances etched an indelible question mark; and later, in the search for elusive meanings usually withheld, the timely aid of early teachers and childhood friends who had long worked among these peoples helped most materially in establishing the basis of confidence needed for transcription.

Pushed in part by a request from Theatre Arts for material explaining certain masks figuring in the Northwest regional dances, an initial sketch (Masks of the Northwest Coast) was completed for a special Theatre Arts issue devoted to the dramatic arts of the American Indian (Aug. 1933). Later, a mass of detail, from hitherto unrecorded territory, concerning various rituals, became the basis of an intensive study encouraged by support from the Research Council of the University of Oregon. From this mass, in the interest of clarity, one single ritual was isolated for more complete recordthe major masked ritual of the lower coast country, and one most deeply expressive of that region. Since the method of approach was by direct observation and word-of-mouth transcription, successive visits to complete and check the record were made to key points within the matrix region: Neah Bay (Makah), where the tribal dances are still held, 1932 on; La Push (Quillayute), 1934-38; the west coast of Vancouver Island, mainly Alberni and Ucleulet (Nootkan), 1936 and 1938; and the Queen Charlotte Islands (Haida), 1940.

The strip of lower coast country stretching northward from Juan de Fuca Strait along the so-called west shore represented a gap in the accomplished work of various anthropologistsmainly in the labors of the late Dr. Franz Boas, whose massive studies of the life and beliefs of tribes to the north and east are well known. In assembling the material for the present record, and in its presentation, the guidance and advice of Dr. Boas were invaluable. His careful reading of the manuscript and detailed comment on its pages gave it direction; the use of the Frachtenberg notes, made at La Push in 1916, courteously loaned by the Bureau of American Ethnology, was at his suggestion. His expressed conviction that the new material from unrecorded territory was of value as source material spurred the completion of the study. And the example of a scholar, tireless in his study and interpretation of Northwest primitive culture, was itself an inspiration and stimulus. The debt is gratefully acknowledged.

Many of the masks used in the Northwest ritual dances were sent out, very early, by explorers or traders for safekeeping in the various museums. Following four seasons of field work, a further study was made of materials thus stored. In the task of checking recorded narrative against related artifacts, and in the matter of illustration, thanks are due Dr. Clark Wissler and Miss Bella Weitzner of the American Museum of Natural History, both for friendly aid and for numerous fine photographs. The generous cooperation of Dr. George G. Heye of the Museum of the American Indian has been constructive and unfailing throughout. The visual record thus made possible has been of prime importance in clearly establishing areas of agreement as to ritual procedure, and in confirming the narratives of informants. A similar search among the considerable body of Northwest material in the Field Museum and at the Smithsonian Institution was greatly assisted by clerical help by staff members and by photographs furnished.

Within the region, the cooperation of many unnamed persons furthered the original gathering of materialaside from the various informants whose names appear in the record. In establishing needed contacts with informants and in gaining foundation material concerning early days on the Olympic Peninsula, the late A. N. Taylor, for many years Indian agent at Jamestown, Washington, E. B. Webster of Port Angeles, Washington, naturalist, and Miss Hannah Draper of the same place, esteemed by the Makahs from early residence at Neah Bay, were very helpful. Farther to the north, a similar list might become encyclopaedic. The continued confidence and understanding of members of the several tribes opened many doors.

Background reading on the social organization and culture of the coast dwellers, carried on in part in the archives of the Provincial Museum, Victoria, B. C. and later in the Northwest collections at the University of Oregon, was assisted by skilled aid from the reference staffs of both these institutions. In the working out of two preliminary studies of the regional ritual dances for Theatre Arts (Northwest Coast Animal Dances, Sept. 1939, and Thunderbird Dance, Feb. 1945) the interest of its editor, Edith J. R. Isaacs, was dynamic. And, in the assembling and sorting of material for the present monograph and the checking of early manuscript drafts, the wide knowledge of William A. Newcombe of Victoria, B. C. was basically helpful; access to the unpublished notes made by his father, the late Dr. C. F. Newcombe, in his early journeys along the Northwest Coast has thrown needed light on dubious points. Without all such generous help this record could not have been completed.