Kilmainham Gaol,

7.5.16.

My dear Annie and Lily,

I am giving this to Mrs. Murphy for you; shell not mind to hear of what is happening, and shell get you all to pray for those of us who must die. Indeed you girls give us courage, and may God grant you Freedom soon in the fullest sense. You wont see me again, and I felt it better not to have you see me, as youd only be lonely, but now my soul is gone and pray God it will be pardoned all its crimes. Tell Christy and all what happened and ask them to pray for me.

Goodbye, dear friends and remember me in your prayers.

Your fond friend

C. O Colbird

The letter of 27-year-old Captain Con Colbert to Annie and Lily Cooney written the day before his execution. ANNIE OBRIEN WS 805

T he 1916 Rising is one of the most written-about episodes in Irelands turbulent history. Less well documented, however, is what happened in its immediate aftermath. Many publications cover the courts martial, deportations and executions as a footnote to a wider subject matter, or take a biographical viewpoint of the leaders, either collectively or individually. A small number of books deal exclusively with the courts martial. We felt, however, that the overall narrative of Irelands revolutionary period was missing a hugely important and no less fascinating focus: the in-depth story of the post-Rising events in Dublin, as well as what followed, from the perspective of those on both sides who were actually there.

For a great many of the participants, what happened in the days, weeks and months after the Rising was probably worse than the fighting itself. In some ways, the combat seen in Dublin and elsewhere during Easter Week was, for those who took part, as exhilarating as it was traumatic. The same could not be said of what came in its wake. Some expressed the wish that they had not survived the insurrection when they found themselves incarcerated in conditions that drove them to the brink of insanity and, on more than one occasion, beyond.

Yet the period between May 1916 and the autumn of 1917 saw the rebirth of the Irish Volunteer movement. Shattered as it was following its military defeat, and reeling from the executions of its leaders, by late 1917 it was beginning, against all odds, to reshape itself into a formidable force which now had a considerable strategic advantage compared with the rebel units who had turned out on Easter Monday 1916. The Volunteers now had widespread public support, shown by the jubilant welcome they received from thousands of civilians when they returned from imprisonment and internment.

Following the final Republican surrenders in Dublin and elsewhere after Easter Week, the men and women of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army were staring into the dark abyss of defeat. Many were unable to comprehend why they had capitulated. They felt a sense of desolation at the shattering of the dream for which they had trained so long and fought so tenaciously. The angry reaction of a huge section of Dublins civilians towards them came as a great shock that added immeasurably to their anguish. Dublin had divided loyalties at the time of the Rising. Despite significant support for the revolutionary cause from many quarters, thousands of Dublins civilians took the opposite view. Many who had relations serving in the British Army saw the insurgents as traitors; others were happy to be part of the British Empire; another significant cohort were content with the promise of Home Rule at a later date, however hollow that promise had proved to be. The Volunteers knew this, and had accordingly expected some backlash, but nothing approaching the levels of venom spat at them, to the point where, more than once, enemy soldiers had to intervene to protect them.

The rebel prisoners who were initially detained in Richmond Barracks in Inchicore faced horrendous conditions. They were kept in overcrowded cells with inadequate ventilation, very little water and abysmal hygiene. Fighting men and women who had not eaten, drunk or slept in days had to face the backlash from cruel and hostile enemy soldiers. They then witnessed the pitiless selection of their more prominent figures by detectives for the military courts. The deportations that followed were both terrifying and stomach-churning. Loaded onto stinking cattle boats, many of them expected to be sunk in the Irish Sea by an enemy determined to take revenge. Some were so dejected at this point that such a fate would have been considered a blessing. Then the authorities exacerbated the trauma of defeat with the executions of the rebellions leaders and more prominent participants.

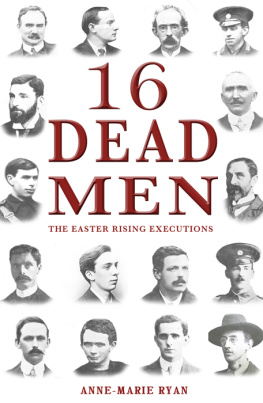

The courts martial that preceded the executions were swiftly convened, and carried out with equal haste. Despite official records being incomplete, our extensive research has enabled us to gain a reasonably comprehensive picture of the more prominent trials, as well as a picture of what the British officers overseeing them thought of their adversaries. Much of it is surprising. The reactions of the Volunteers to the trials varied. Some wanted nothing to do with them and effectively refused to acknowledge their authority. Others were aghast at the apparent disregard for due process afforded them, a sentiment shared by their most prominent prosecutor, Lieutenant William Wylie.

The executions that took place following the courts martial have been well documented in terms of their victims personalities, their histories, and their positions in the revolutionary movement. Their chronology is generally well known. However, we felt that there was still a dearth of literature about what happened when the actual executions took place. This is something we have endeavoured to put to rights in this book. Seven of the 14 men shot in Kilmainham Gaol were, after all, in effect the founding fathers of the Irish Republic, having signed the proclamation that underpinned it. Much has been spoken and written of their and the other condemned mens lives, and indeed of their poignant final hours, but comparatively little has been written of what actually took place in the Stonebreakers Yard when they were put to death. There are, of course, numerous detailed written accounts recorded by the monks who ministered to the condemned men as their final hour approached, but from the perspective of those who had the unpalatable task of carrying out the executions there are comparatively few details.

![Lorcan Collins [Lorcan Collins] - 1916: The Rising Handbook](/uploads/posts/book/143326/thumbs/lorcan-collins-lorcan-collins-1916-the-rising.jpg)