Contents

Once again I have to acknowledge the invaluable contribution of my friend and former colleague, Walter Grey. Besides our many enjoyable discussions about Tom Clarke, Walter read various drafts of the book and made many constructive suggestions for improvement. I am forever in Walters debt. I also want to thank my oldest friend, Dr Brian Barton who suggested that I write a life of Tom Clarke. Dr Timothy Bowman, Dr Michelle Brown and Stewart Roulston read and commented on the books final draft. I also received important help from Liam Andrews, Ken Boden, Lisa Dolan, Rev. Barbara Fryday, Gerry Kavanagh, Colette ODaly and John Tohill. Once again I am indebted to Helen Litton who indexed the book. I would also like to express my gratitude to three members of The History Press Ireland: Beth Amphlett who commissioned the book, Ronan Colgan, and Gay OCasey who edited the text.

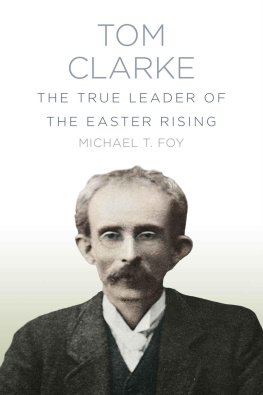

Michael T. Foy

In the year 1847 when much of rural Ireland was in the throes of the Famine, a 17-year-old farmers son from Co. Leitrim joined the British Army. For James Clarke that was not an unusual choice as a member of the small, scattered Protestant minority near the western fringe of Ulster and loyal to the British connection. Seven years later as a soldier in the Royal Artillery he was fighting in the Crimean War at the battles of Alma and Inkerman and taking part in the siege of Sevastopol. After the conflict ended in February 1856, his regiment transferred to Clonmel, Co. Tipperary where James was promoted to bombardier.

In Clonmel James met Mary Palmer, a Roman Catholic servant girl. On 21 May 1857 they married in Clogheen at Shanrahan Anglican parish church. Like many of her social class at the time, Mary could not read or write and made her mark in the register. Since in that period the Church of Ireland to which James belonged alone issued marriage licences, Roman Catholics like Mary often married under its auspices, though she insisted that any children the couple had would be raised in her religion.

Thomas James Clarke, the subject of this book, was their firstborn. Hitherto it has been accepted that Thomas was born in 1858 at Hurst Park Barracks on the Isle of Wight where Jamess Royal Artillery regiment was stationed at the time. One historian, though, has asserted that Thomas was born at Hurst Castle an abandoned fort on the Hampshire coast that had not had a military garrison for over 150 years and which during the eighteenth century had become a favourite haunt of smugglers. But the records show no Thomas James Clarke born on the Isle of Wight or in the nearby county of Hampshire during the entire 1850s, nor is anyone of that name listed in the British Armys births and baptisms for England and Ireland during 1857 and 1858. Furthermore, Clarkes widow Kathleen asserted that her husband had been born on 11 March 1857 and celebrated his fifty-ninth birthday just before the Easter Rising in 1916. The inference is that Thomas James Clarke must have been born out of wedlock in Co. Tipperary. Over the next twelve years, James and Mary had three more children two girls, Maria and Hannah, and a younger son, Alfred. In April 1859, James, Mary and their then only child Thomas accompanied the regiment to South Africa, almost drowning on the way when their ship was involved in a serious collision.

After five and a half years the Clarke family returned to Ireland and, after being honourably discharged from the Royal Artillery in January 1869, James joined the staff of the Ulster Militia Artillery. With no married quarters available in the militia barracks, James and his family lived in Dungannon, a rather drab provincial town in Co. Tyrone whose arid social life came to a dead stop on Sundays. Evenly balanced between Protestants and Catholics, the town was dominated by its centuries-old sectarian struggle between Unionism and Nationalism. Tyrone had been a cockpit of religious and political antagonism since the Ulster Plantation and the county was also a heartland of the great ONeill clan that in Tudor and Stuart times had provided two notable rebels against English power Hugh ONeill, Earl of Tyrone and his nephew, Owen Roe. This bitter county was the centre of Thomas Clarkes small world. Only the newspapers connected him to outside events and he travelled little, apparently never even visiting Belfast, 50 miles away.

Now known universally as Tom, Clarke attended St Patricks National School in Dungannon. Under the monitor system he became an assistant teacher but was eventually let go because of falling rolls. Clearly intelligent and well read, Tom became an enthusiastic amateur actor in Dungannons Dramatic Club. But politics was his all-consuming passion and he came to espouse the cause of Irish independence. This commitment divided the Clarke family because his father had for decades served proudly as a British soldier and his brother Alfred had also enlisted in the Royal Artillery. Any early influence that his mother, who came from a very different background, might have had on Toms ultimate political beliefs remains a matter for conjecture. When James Clarke warned his son that defying the British Empire meant banging his head against a wall, Tom retorted that he would just keep going until the wall fell down. His rebelliousness was certainly not rooted in a miserable childhood. The Clarkes were a happy family and Tom respected and admired his father, rejecting only his army uniform; the bonds with his mother and siblings stayed strong and harmonious. Much more influential in shaping his political consciousness was Toms time in South Africa. Increasingly hostile to the British Army, he came to regard it as an imperial garrison that oppressed not the black population then politically invisible but the Boers, Dutch settlers for whom Tom developed a lifelong sympathy. But it was on his return to Ireland that Toms political ideas really crystallised. Only a few years after the Fenian Rising of 1867 the British Army and Royal Irish Constabulary were still highly vigilant and visible in Co. Tyrone. And in bitterly divided Dungannon memories of the Irish Famine remained vivid, while an agricultural depression during the late 1870s exacerbated a traditionally turbulent relationship between landlords and tenants. The town also experienced frequent sectarian rioting between Protestants and Catholics.

In 1878 Tom attended an open-air meeting outside Dungannon addressed by John Daly, a national organiser of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). A superb public speaker with a powerful physique, imposing presence and magnetic personality, the 33-year-old Dalys oratory mesmerised audiences and his vision of an independent Ireland left Clarke deeply impressed. Suddenly Tom realised that his mission in life was to destroy every vestige of British authority in Ireland Crown, Viceroy, Army and the Dublin Castle administration, the entire colonial system. He espoused the same goal as Wolfe Tone, his greatest historical inspiration. Almost a century earlier, Wolfe Tone, the father of Irish republicanism and instigator of the 1798 Rebellion, had set out to subvert the tyranny of our execrable government, to break the connection with England, the never-failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country. And from this goal Tom himself was never to deviate. Later in 1878, after the Dungannon meeting, Clarke and his best friend Billy Kelly joined a Dramatic Club excursion to Dublin where Daly swore them into the IRB. But after becoming the organisations Dungannon secretary, a disillusioned Clarke discovered that his idealised vision of the IRB as a sword for smiting England was very different to the drab reality of a society that had seriously lost its way. He was to spend the rest of his life remedying that situation.

Next page