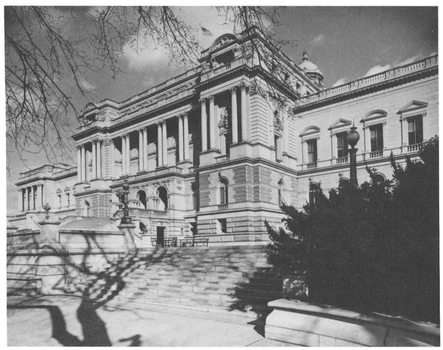

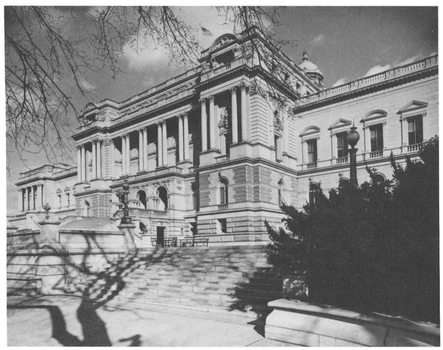

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

The west front of the 1897 Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress.

Westview Library of Federal Departments, Agencies, and Systems

The National Park Service, William C. Everhart

The Forest Service, Michael Frome

The Smithsonian Institution, Paul H. Oehser

The Bureau of Indian Affairs, Theodore W. Taylor

All photographs courteously provided by the Library of Congress.

First published 1982 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1982 by Charles A. Goodrum and Helen W. Dalrymple

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Goodrum, Charles A.

The Library of Congress.

(Westview library of federal departments, agencies, and systems)

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Library of Congress. I. Dalrymple, Helen W. II. Title. III. Series.

Z733.U6G67 1982 027.373 82-8457

ISBN 0-86531-303-2 AACR2

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-29355-0 (hbk)

This book, an attempt to describe how the world's largest library works, was first written at the beginning of the seventies. At that time the Library of Congress was struggling to cope with four recent shocks that had jarred the even tenor of its ways. The intellectual community was reacting to the challenges of Sputnik and Soviet technology, the social community was building the Great Society, Congress was expanding under a series of structural reforms, and the Library's traditional role of the keeper of all knowledge placed it at ground zero in the information explosion. It was an interesting time to write about.

A decade has passed since then, and, assuming that enough progress must have occurred to require at least an updating of the statistics, the publisher asked us to make the text current. We started the task routinely enough, but soon learned to our chagrin that there had been more dramatic changes in the Library's life in the seventies than in the previous fifty years.

Under the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, the Legislative Reference Service had gone from 306 employees when the Act was passed to become the Congressional Research Service with a staff of 868 in 1980. More important, both its purpose and its way of doing business had changed. The Copyright Office had undergone a revolution as the result of the first statutory revision of the copyright law in 64 years, and the Copyright Law of 1976 had turned a book-oriented register into a cable television, videodisc, phonograph franchise factory. The Division for the Blind, with a budget of $7 million in 1970, had become the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, with a 1980 appropriation of $34.5 million (larger than the total budget of many major universities). And so on, through dozens of departments and divisions.

We found that the questions for (and about) the Library had changed too. In 1970 we were asking, Should the Library be moved to the Executive Branch? For the moment, that question is moot. By 1980, the question had become, What do you use a national library for? or even, Do we need a national library at all? In 1971 Library officials were worried about providing printed catalog cards at the rate of 74 million a year to 25,000 "outside" libraries. By 1981 the Library had closed down its own card catalogs completely, was totally reliant on its computer to control and retrieve its current and future holdings, and had turned to printing cards a single copy at a time as outside libraries requested an entry for their traditional catalogs. We found that revisionism had even overtaken the history of the Library, and two of its hoariest legends required modification.

Ultimately almost every page of the original book had to be rewritten. New programs and vastly new and larger problems required the creation of four completely new chapters just to get the story caught up to the necessarily brisk account of the original volume, and once more we are in debt to everyone who helped us. We returned to the organizational units and asked not, What are the figures now? as we had expected, but, What's new? What are you doing now? What will you be doing in 2001? What we learned is the book before you.

This book is in no way an official statement of the Library management. Between us, the authors have spent over fifty years on the Library staff, but neither of us is presently employed by the Library, and the perceptions of the institution are neither ours nor the Library leadership's as such. Although the reader is always at the mercy of what the authors decided to talk about, what is reported here is (if our intent has been successful) what the concerned people throughout the Library's middle and upper management are thinking. The thoughts include some by "the administration," but the administration made no attempt whatever to suggest what we should say. By the same token, staff members throughout the Library gave us great amounts of time, with great civility and candor, for which we are most grateful.

Although we tried to keep the statistics to a minimum throughout the book, one of the aspects of the Library that is clearly news is its scale. Thus, we tried to provide figures when they would give a basis for comparison with other institutions with which the reader would be familiar. Whenever a year date is given, it is a federal government fiscal year, which runs from October 1 to September 30. The year date refers to the year of the final date, so a sentence reading, "In 1980, the Library discarded 8.5 million volumes," means "in fiscal year 1980," or literally, "from October 1979 through September 1980, the Library..."

Enough. This is an exciting time at the Library of Congress. Not since the institution moved out of the Capitol to start its new life as the national library in the great gray building across the street has there been such a feeling of "the end of one book, the beginning of another." We hope we have been able to capture a little of that excitement for you in the volume that follows.