Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2012 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wolff, Larry, author.

Paolinas innocence : child abuse in Casanovas Venice / Larry Wolff.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-6261-8 (cloth : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-8047-6262-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)ISBN 978-0-8047-8210-4 (e-book)

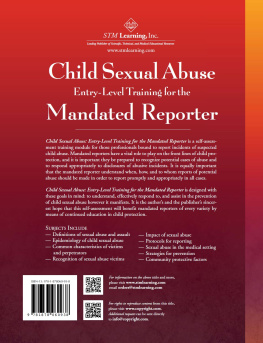

1. Franceschini, Gaetano, 1725?Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Lozaro, Paolina, 1777Trials, litigation, etc. 3. Trials (Child sexual abuse)ItalyVeniceHistory18th century. 4. Child sexual abuseInvestigationItalyVeniceHistory18th century. 5. LibertinismItalyVeniceHistory18th century. 6. Sociological jurisprudenceItalyVeniceHistory18th century. I. Title.

KKH41.F73W65 2012

2011045204dc23

2011045204

Typeset by Bruce Lundquist in 10.5/14 Adobe Garamond

Paolinas Innocence

CHILD ABUSE IN CASANOVAS VENICE

Larry Wolff

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

For Sheila Klass and in memory of Mort Klass

Always scribble, scribble, scribble! Eh, Mr. Gibbon?

Contents

Acknowledgments

Although my research for many years has focused on Eastern Europe and the Habsburg monarchy, I have also maintained a strong interest in the history of childhood. Ive taught a course on parents and children in European history and have published, over the years, articles on cultural conceptions of childhood, ranging in subject from Mme de Svign in the seventeenth century, to Jean-Jacques Rousseau in the eighteenth century, to Charles Dickens in the nineteenth century. In 1988 I published a book about child abuse in Freuds Vienna, and this new book on child abuse in Casanovas Venice is a closely related work. Each book attempts to understand abuse in a complex cultural context, which for all its complexityin Casanovas Venice as in Freuds Viennadid not include a clearly articulated sense of child abuse as a sociological phenomenon. The documentary basis for Paolinas Innocence is an unexpectedly fat archival file of some three hundred pages, which I came upon in the Archivio di Stato in Venice when I was working on an entirely different subject, Venetian rule over the Slavs of Dalmatia in the eighteenth century (eventually published in 2001 under the title Venice and the Slavs). I found this file at the very end of one of my archival visits to Venice. I remember beginning to read it, becoming instantly fascinated with the story of Paolina Lozaro and Gaetano Franceschini, and then having to make the tough decision as to whether I should keep on reading or send the entire file to be microfilmed and, eventually, mailed to me in Boston where I then lived. I requested the microfilm and therefore had to wait quite some time to learn the details of the case.

Over the last decade, first in Boston and then in New York, I have been looking for both the necessary time and the appropriate form in which to make this material into a book. I have enjoyed the support and encouragement of colleagues at both Boston College and NYU. I am likewise exceptionally grateful for the assistance and companionship of the archivists and scholars I encountered at the Archivio di Stato in Venice, as well as the kind assistance I have received at the Biblioteca Marciana and Biblioteca del Museo Correr in Venice, and the Archivio di Stato in Vicenza. I received financial support for my research from the Gladys Krieble Delmas Foundation.

I have greatly benefited from discussions of this project in particular, and the history of childhood more generally, with Maria Tatar, Paula Fass, and Tara Zahra. I have been glad to have the opportunity to discuss the early modern implications of this project with Mario Biagioli, Pierre Saint-Amand, and Andrei Zorin. I was fortunate to be able to present portions of this research at exceptionally stimulating conferences and seminars at the Princeton Cotsen Childrens Library, at the cole des Hautes tudes en Sciences Sociales in Paris, at the Voltaire Foundation at Oxford, and at the University of Primorska in Koper, Slovenia. My work, as presented at these conferences, then benefited further from publications under the editorship of Andrew Kahn, Claudio Povolo, and Irina Prokhorova of the New Literary Review in Moscow.

In the early stages of this project I was given enthusiastic encouragement and advice by two scholars whose thoughts I hugely valued and who died before the book was complete: Morton Klass and Stephen Jay Gould. As always, I am grateful to my parents, Bob and Renee Wolff, for their spirited interest in my research. At NYU I have to thank Stefanos Geroulanos for helping me prepare the images to accompany the text. At Stanford I am very grateful to Norris Pope, not just for publishing this book but for publishing so handsomely five books over almost twenty years, and thus personally overseeing almost my entire academic career. Finally, at home, I could not have written this book without Perri Klass, who has lived with this project for a long time and who read and edited the entire manuscript. All my thoughts about children and the history of childhood owe just about everything to her.

Introduction

In the summer of 1785 a Venetian tribunal initiated the criminal investigation of a sixty-year-old man who had been accused of having sexual contact with an eight-year-old girl. In the eighteenth century there was no clear clinical or sociological concept of child sexual abuse, as we understand it today, and the judicial investigation of this particular case kept growing in scope as the court attempted to determine what exactly had happened to the child, Paolina Lozaro, during a single night in the apartment, and the bed, of Gaetano Franceschini. She was the daughter of a poor laundress from the immigrant Friulian community in Venice; he came from a wealthy family of silk manufacturers in Vicenza. The details of the case were difficult to discover, and even more difficult to prove, for the child herself barely understood what had happened to her, but even the contested facts of the case were complicated by controversial cultural questions. The tribunal had to decide whether, and in what sense, the girl had actually been harmed; whether, and in what sense, the mans actions were criminal; and, if so, how he should be punished. There were no simple and straightforward answers to these questions in the eighteenth century. The case began with a single-page secret denunciation to the law, composed by a neighborhood priest who had heard that Franceschini slept with the girl scandalously in his own bed. The judicial dossier then accumulated testimonies of witnesses and documents of indictment and defense to the eventual length of some three hundred handwritten pages.

While it seems plausible to suppose that the mistreatment of childrenwhat we call child abusewas at least as common in earlier centuries as it is today, the absence of the modern concept of abuse meant that such mistreatment left relatively little documentary trace in the archival records. The three hundredpage dossier concerning the case of Gaetano Franceschini and Paolina Lozaro in 1785 may be, very possibly, the most detailed investigation of child abuse ever carried out and recorded in the world of the ancien rgime. The dossier may be found in the records of the tribunal of the Esecutori contro la Bestemmia (Executors against Blasphemy), and that peculiar jurisdiction already suggests some of the difficulty in specifying and classifying the crime under consideration. Consistent with the denunciation that Franceschini kept the girl scandalously in his own bed, the principal charge against him was the very generally conceived crime of causing scandal. Paradoxically, the case did not cause scandal because it was clearly criminal but rather was deemed judicially criminal because it was the cause of neighborhood scandal. Cultural and social perspectives on childhood thus partly conditioned the legal course of the prosecution.