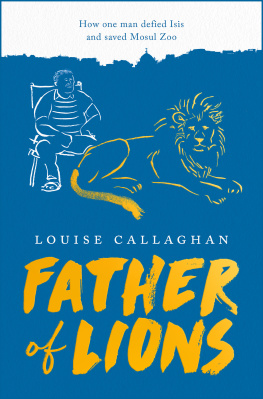

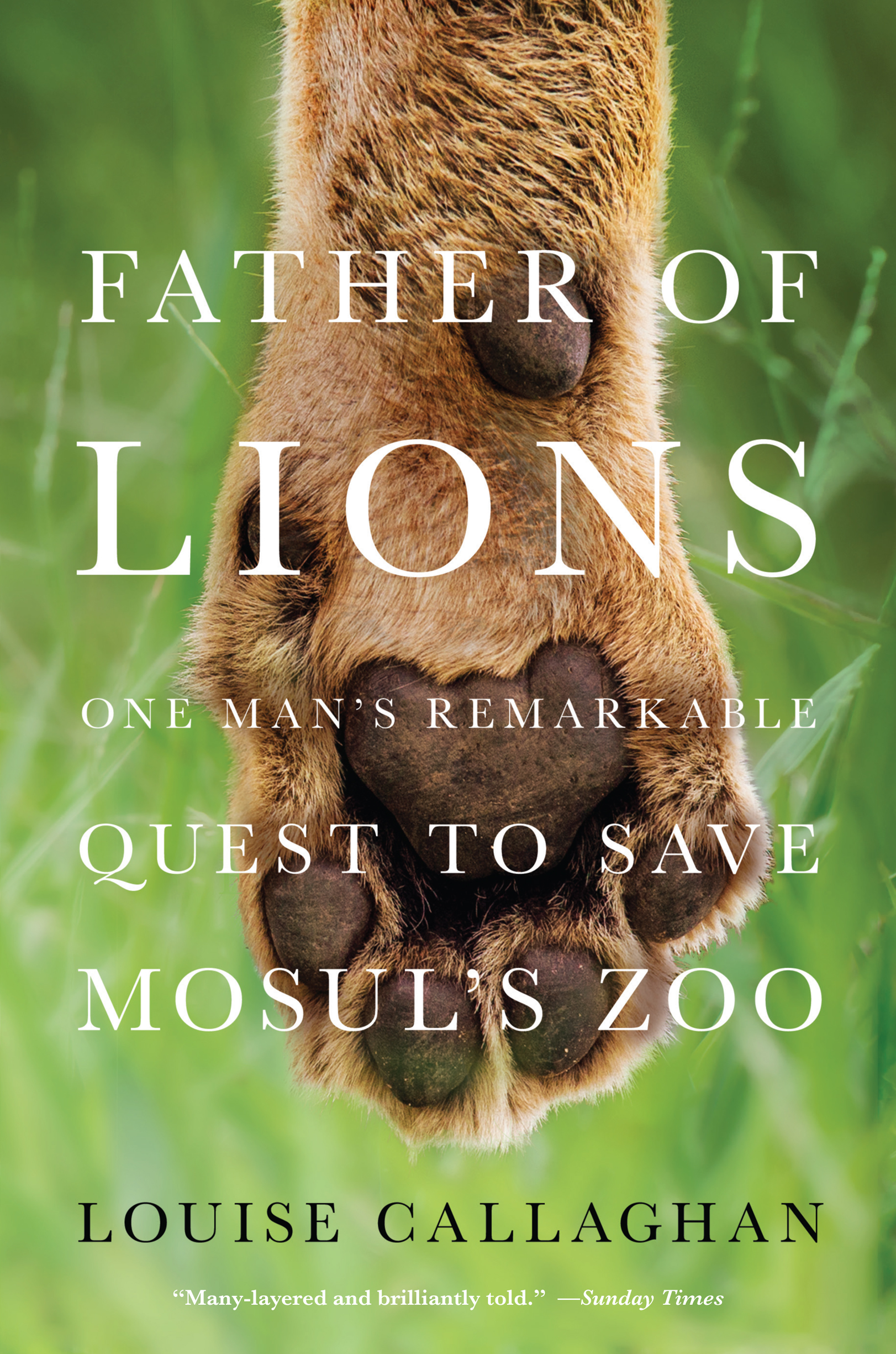

Abu Laith was not the kind of man to let another man insult his lion. Especially not a man who looked like this.

He was wearing a short-sleeved shirt, well pressed, and had the air of a civil servant. He carried a baby in the crook of his left arm. In his right hand he held a reed, plucked from the banks of the River Tigris, which he was using to poke Abu Laiths newly acquired lion cub, who was asleep in his cage.

The mans wife and the rest of his children stood nearby, watching sullenly. Despite his efforts, the poking was having no measurable effect on the lion, who wasnt moving at all. All of this registered in Abu Laiths mind as he ran at full pelt through the zoo towards the man, who had not seen him coming.

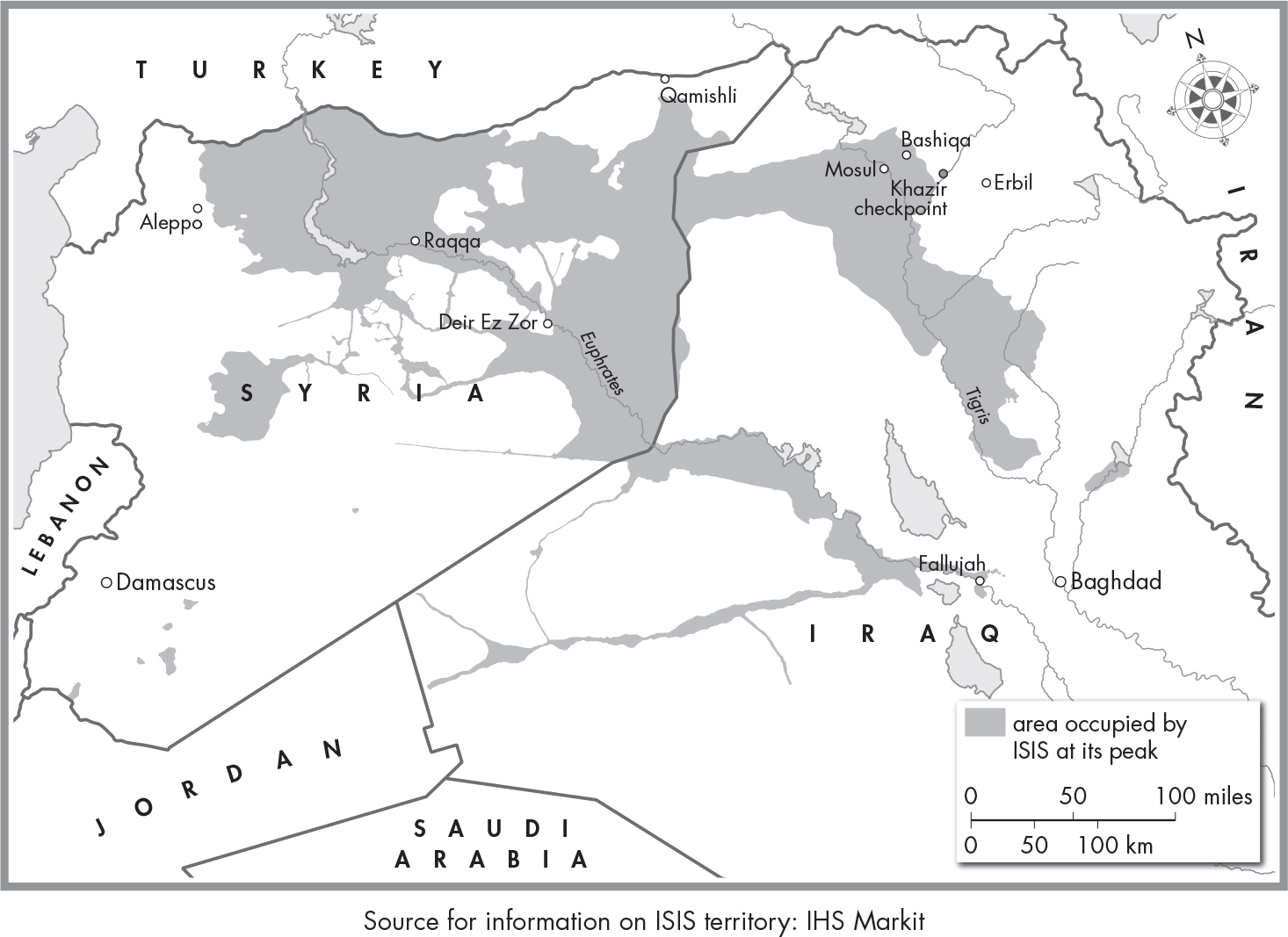

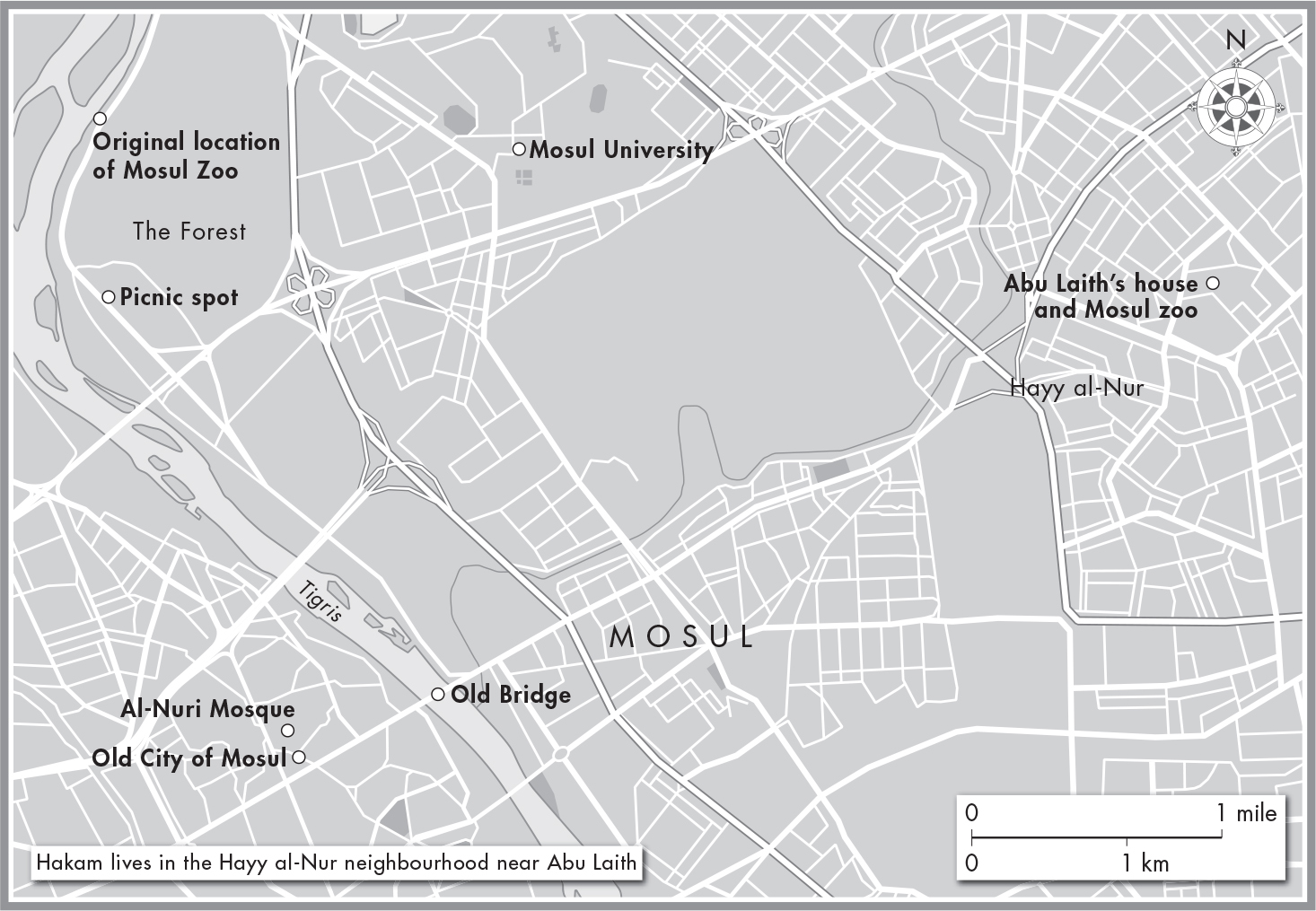

It was around 7.30 p.m. in the zoo by the Tigris, and the dusk was settling pink over Mosuls Old City. Families were sitting outside the zoo cafe drinking cold Pepsi and glasses of tea. The bears were reclining in their cages as Abu Laith charged past.

What are you doing? shouted the self-appointed zookeeper, who rarely spoke at less than a bellow. Get out of the zoo.

The man, who did not realize the danger he was in, barely glanced up. Why arent they doing anything? he asked, irate. We paid money to see them.

Abu Laith came to a dead halt in front of the family. Theyre full, he shouted. Theyve just eaten. When animals are full, they sleep.

The man, who wasnt listening, kept poking at the lion cub. Next door, the lions mother and father known to the zoos employees as Mother and Father were also asleep.

We paid money to see them move, the man said, prodding the lion cub again.

How would you like it if I poked your children with a stick? Abu Laith spat, advancing on the family.

The man, who had finally got the message, backed away, his wide-eyed family backing with him. Im not coming here again, he said, snippily.

Good, called Abu Laith, as the visitors turned and scuttled off. And you had better not, because if you do Ill feed you to my lion.

Grumbling to himself, Abu Laith turned his attentions to the cub. He was sound asleep, and looked not unlike a middle-sized ginger dog. None of the zoo workers, who were milling aimlessly around the park, had reacted to Abu Laiths outburst. They were used to it.

Everyone always said that Abu Laith himself looked like a lion, and it was true. He was five foot six with a rock-hard keg of a belly and an opaque halo of orange hair. His nose looked like it had been hewn from a boulder and sprinkled with freckles. He spoke in a roar.

That was why they called him Abu Laith, which loosely translated meant Father of Lions.

Since he could remember, Abu Laith had loved animals, and devoted himself to them at the near-absolute expense of humans. He had raised dogs, pigeons, rabbits, cats and beetles and held them in his hands when they died. For his third-eldest daughters birthday, he had driven a herd of sheep into the family home. He had once given a baby monkey a shower in his garden.

He had one ultimate, lifelong ambition: to live on a farm with large predators roaming free around him. In Mosul, this was considered a suspect ambition. It had, possibly, something to do with the restrictions on animals in the Quran and the Hadith. In the holy texts, dogs were listed as haram forbidden along with pigs, donkeys, wolves, glow-worms (and all such bloodless animals), snakes and chameleons (animals that have blood, but whose blood does not flow).

Most people, even if they werent religious, thought that dogs were dirty, and somehow unsavoury, in the way that people in Europe felt about rats: plague carriers and unclean beasts that defiled their surroundings. Though some families kept pets, it was considered disreputable to own a lot of animals. Among the people of the great city by the Tigris, animal lovers had a shady reputation as hustlers, fighters and panhandlers. Pigeon breeders, a fraternity to which Abu Laith also belonged, were especially dodgy.

Under the Iraqi legal system, pigeon owners were not considered trustworthy enough to testify in court. They had a reputation for always getting into fights and drinking too much whisky. Abu Laith fitted the stereotype all too well. He was a shaqawa a kind of good-hearted neighbourhood thug. The sort of man you might call if you needed an extra pair of fists in a fight, or if someone was harassing your daughter, and needed to be scared off. He would never let anyone else pay for lunch, and always lent money to his relatives, grasping as he thought they were.

Since he was a young man, Abu Laith had made his living as a mechanic, fixing cars in the neighbourhood. At first hed earned a few dinars here and there, but now he ran a big garage with several employees, where he charged hundreds of dollars to fix large American cars of the kind favoured by Mosuls elite. But this was nothing more than a distraction from his real love: large, dangerous animals.